Uncovering JAPA

Challenges to Ambitious Planning in a Shrinking City

Youngstown, Ohio, was once known for having one of the fastest-declining populations in the United States. It was also notably the first to adopt a comprehensive plan that emphasized "smart shrinkage," a planning strategy that seeks to adjust land use patterns to cities' shrinking populations.

In "Plan Implementation Challenges in a Shrinking City" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 85, No. 4), Brent D. Ryan and Shuqi Gao examine Youngstown's challenges in implementing smart shrinkage as outlined in the city's 2004 comprehensive plan — the "Youngstown 2010 Citywide Plan."

Assessing Smart Shrinkage Implementation Challenges

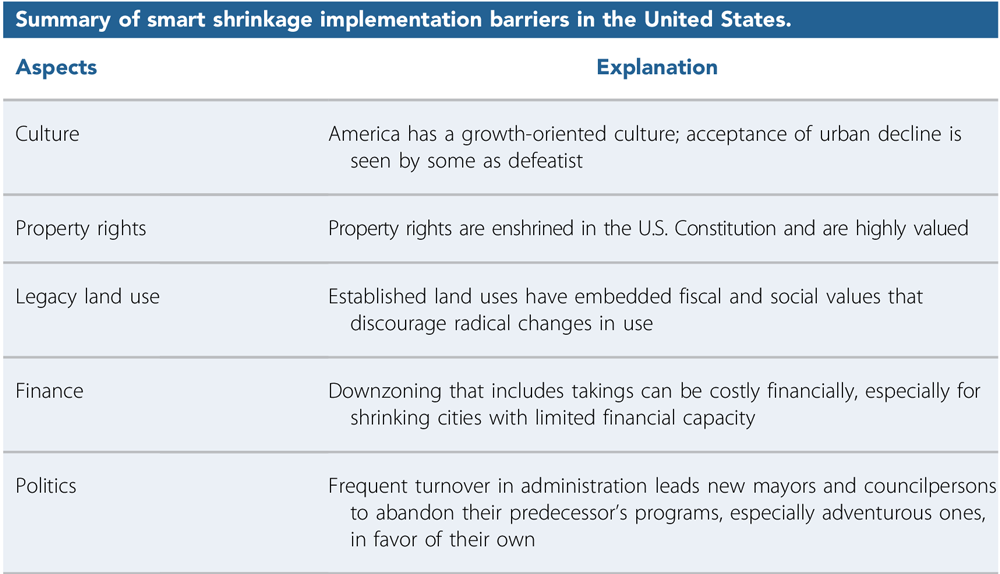

This article reveals complex legal, financial, and political challenges that confronted planners and communities considering smart shrinkage as a planning tool. More broadly, the authors ask what difference "conceptually ambitious," nonstatutory comprehensive plans can make in most communities in the United States, where entrenched property rights and takings arguments can thwart broad rezoning efforts.

The authors asked, to what degree was the smart shrinkage land use agenda of the Youngstown 2010 nonstatutory plan implemented in the city's 2013 zoning reform? To answer this question, Ryan and Gao measured the degree of conformance between land use patterns in the Youngstown 2010 plan, and the corresponding land use designations in the city's 2013 "Youngstown Redevelopment Code."

The authors use spatial analysis and qualitative research to assess conformance and performance, including any discrepancies.

Five barriers faced by smart shrinkage planning in the United States. From "Plan Implementation Challenges in a Shrinking City" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 85, No. 4).

In 2004, the comprehensive plan laid out a broad vision for rezoning many of Youngstown's vacant parcels. It recommended an open space system to replace large amounts of residential parcels, without regard to existing tenure.

Unrealized Goals and Complex Challenges

Using GIS mapping, the authors show that the 2013 zoning code rezoned only 2.6 percent of the city's parcels, leaving the rest unchanged. The 2010 plan's goal to shrink residential land by 30 percent was unrealized, with a total residential area showing little change in the 2013 code.

In some areas, they found stronger conformance between plan and zoning. For example, the 2010 plan designated 1,500 hectares as "open space" and large industrial parcels as "green industrial." The 2013 code designated twice as much open space as the zoning that preceded it. The conversion of vacant industrial to green industrial was also partially achieved, yet in sum, the authors' spatial analysis reveals that the ambitious goals of Youngstown 2010 remained mostly unrealized.

The authors' qualitative research, consisting of semi-structured interviews with planners, revealed compelling reasons for the limited implementation.

The challenges in translating the comprehensive plan's smart shrinkage ideas into zoning regulations were complex, spanning political, cultural, and economic dimensions.

Legal barriers to rezoning were significant: large numbers of Youngstown's vacant parcels were still tax compliant, increasing the risk of rezoning being subject to takings claims. Adding to these legal barriers, financial challenges limited the conversion to open space of empty land zoned residential and commercial.

The required "just compensation" for property owners constituted too large a financial burden for cash-strapped Youngstown to consider, so the residential and commercial zoning remained, even though the land was vacant.

Smart shrinkage implementation also faced political and cultural limitations as both city council members and newly elected administrations found the plan's anti-growth orientation unpalatable. The 2010 plan was innovative, but there was little incentive to implement a former administration's policy.

Perhaps the authors' most provocative argument is that neighborhood plans, rather than nonstatutory, citywide comprehensive plans, might be a more promising tool to project futures for economically, and demographically declining cities.

Narrower in scope and scale, and less contingent on public consensus and legislative action, neighborhood plans offer a practical advantage in tackling persistent and widening problems associated with disinvestment in mid-size U.S. cities such as Youngstown.

Top photo: Getty Images photo of Youngstown, Ohio.