Uncovering JAPA

The Hidden Cost in Housing Affordability

There is more to housing affordability than finding a place with a reasonable rent.

Often forgotten are the hidden costs, like utilities, that come along after one has secured housing. Such costs go largely understudied as solutions to issues of affordability affecting communities throughout the U.S., but they are at the forefront of Constantine E. Kontokosta, Vincent J. Reina, and Bartosz Bonczak's article "Energy Cost Burdens for Low-Income and Minority Households" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 86, No. 1).

Hidden Energy Costs for Low-Income Households

Using five cities in the United States with publicly available energy disclosure data — Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts; New York City; Seattle; and Washington, D.C. — the authors estimate energy cost burdens for 7,841 multifamily properties. Their results reveal that high- and low-income households consume the greatest amounts of energy.

However, the difference between the households is simple. For higher income households energy use relates to how one lives. For low-income households, it is where one lives.

Higher-income households tend to occupy larger units and engage in activities that require greater amounts of energy. However, despite having smaller units, poor building efficiency often necessitates higher energy consumption among lower-income households. Across all households in the study, the amount of income put toward utilities averages between 1.5 percent and 3 percent. However, low-income households could expect to pay 10 percent, with some households spending as high as 20 percent of their income on utility costs. Along with the cost of rent itself, these households have the potential to be severely cost-burdened.

Further, even among low-income communities, there remains a disparity.

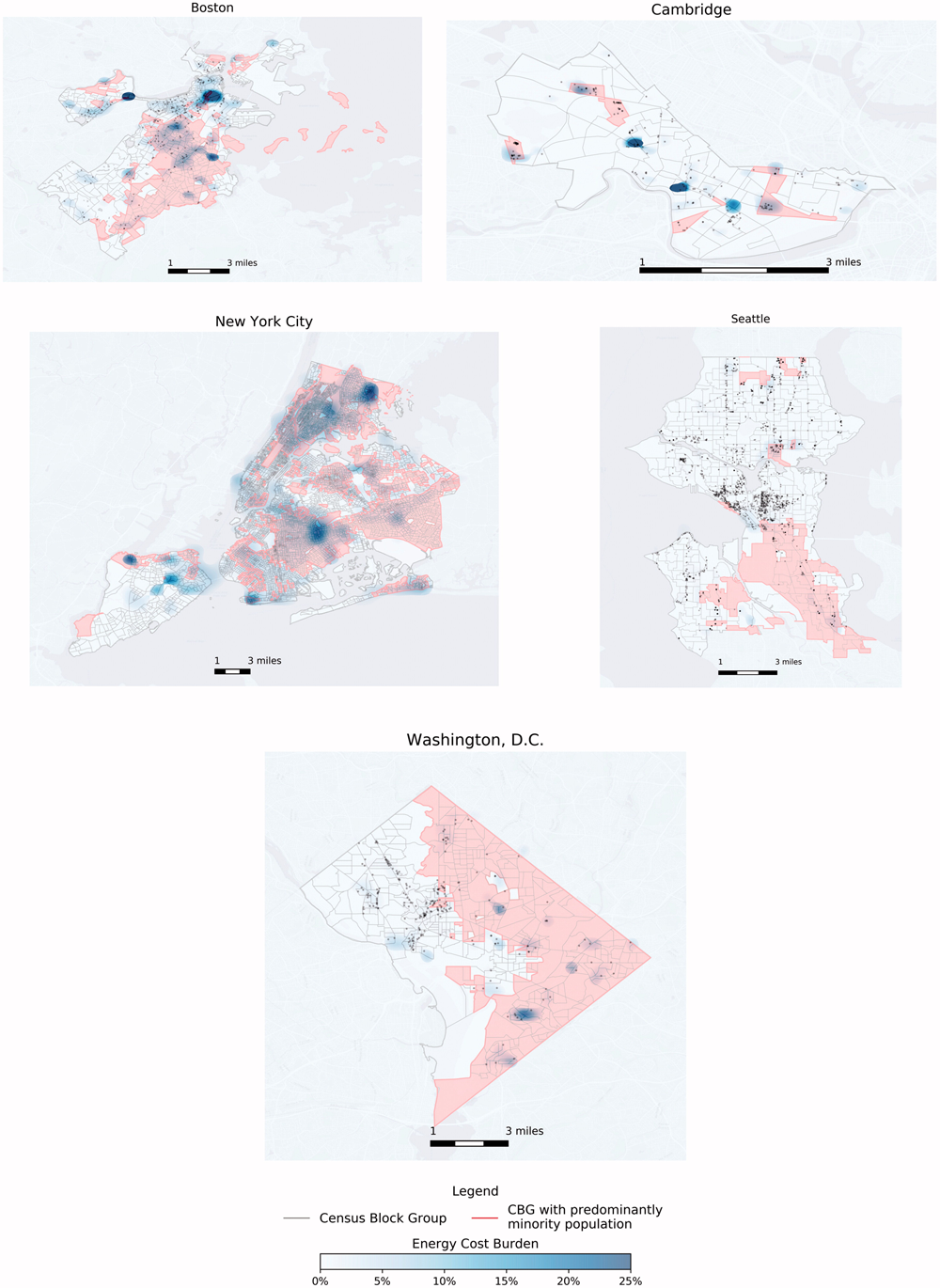

In each of these cities, high energy cost burdens (ECB) were concentrated in areas often aligning with predominantly minority communities. The authors find that "[v]ery-low-income residents (50% AMI) in predominantly minority neighborhoods experience a 1.56-percentage-point higher ECB than do low-income residents in predominantly non-Hispanic White communities, which equates to a 27% greater ECB on average."

Spatial dispersion of energy cost burdens (blue heat map), properties (in black), and neighborhood classification (predominantly minority census block groups in red) in selected cities, 2015. Figure 3 from the article "Energy Cost Burdens for Low-Income and Minority Households" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 86, No. 1).

Energy Justice for Housing Equity

So what can planners do to promote energy efficiency and, more importantly, energy justice? As the article illustrates, planners must begin to understand the extent high ECBs contribute to the affordability of housing. However this first requires access to such data.

The authors put forward several recommendations to reduce high energy cost burdens including changes to lighting, pipe insulation, and installation of domestic hot water systems. However, many of these changes are small in scale requiring owner support. Regardless, with this information planners too can think big, changing developmental standards to require energy efficiency measures in new housing stock. But even here there is a challenge.

Few multifamily housing properties are likely to be built in predominantly minority communities, and those that are likely will not house very low-income households.

Energy justice might assuage issues of housing affordability, but if we intend to solve housing affordability we need more. We cannot continue to look at housing and its ancillaries, like the energy to live decently, as commodities. True housing justice and energy justice are only possible when these costs are decommodified. That's where our focus should be.

Top image: Utility meters. Getty Images photo.