Uncovering JAPA

The Transgressive Urban Forest

Trees in cities serve multiple purposes. They provide shade to residents, create habitats for wildlife, and purify air and water. Trees also provide an aesthetic value to city dwellers by integrating greenery into the built environment. City planners have upheld these values through investments in tree plantings, municipal parks, and other forms of urban nature.

However, this aesthetic vision is not without its critics. In "The Transgressive Urban Forest: An Ecological Aesthetic for the Anthropocene" Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 88, No. 3), Lucie A. Laurian, Ernest Sternberg, & Nadia Voigt da Mata argue that the manicured urban landscape disconnects city dwellers from the global ecological crisis.

Provocative Urban Forestry Challenges City-dweller Complacency

They describe the existing approach to urban ecology as "deceptive self-indulgence about the compatibility of city and nature." By maintaining an aesthetic of urban nature that is trimmed, hedged, and mowed, city dwellers are sheltered from the consequences and effects of climate change.

The authors do not reject urban nature out of hand. Indeed, they call attention to the numerous ways in which urban landscaping supports necessary ecosystem services. As they note, "Urban environmental planning has evolved to include stormwater runoff infiltration, ecological restoration that regenerates habitats, and tree canopy programs to reduce heat island effects." Yet while these functions are valuable, they are preserved through an urban landscape that "deadens city dwellers to their destructive relationship with nature."

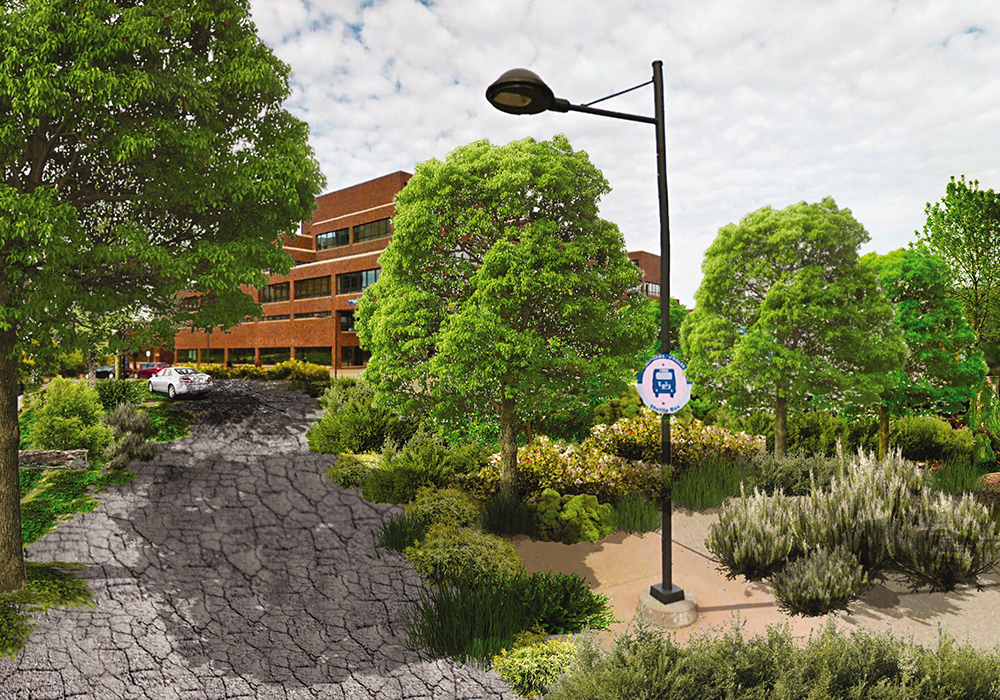

Figures 1 and 4: Visualizing the transgressive urban forest at SUNY Buffalo North Campus and in downtown Tulsa.

Radical Urban Forestry Challenges Norms

As an alternative, they provide a more radical conception of urban forestry. The authors advocate for a landscape that is designed to "disconcert, awaken, and provoke."

In their vision, trees will be "released from their roles as reassurers of city–nature harmony" by breaking free from their manicured settings and infiltrating the built environment. They describe a vision of an urban landscape wherein "trees will be in-your-face provokers, confronting urbanites with the specter of environmental fragility and threat." Renderings depict what the authors mean by this.

I found the author's critiques of anesthetized urban landscapes interesting, but I wonder about the practical implications of the transgressive urban forest. For one thing, how does this approach to urban ecology support or inhibit environmental justice goals? How might low-income center-city neighborhoods with fewer trees address these issues? What is the relationship between the transgressive urban forest to other urban green spaces and how do the authors envision the future of existing urban parks? These are issues to investigate in future work.

Top Image: iStock/ Getty Images Plus — hallojulie