The First Principles of Urbanism: Part II

Previously, I shared the results of an effort we undertook at Sidewalk Labs to think through the first principles of urbanism. To recap, we concluded that urbanism is density.

Yes, yes — big shocker.

But the more significant takeaway is that what makes cities more or less attractive over time is how the efficiencies of density are balanced against the costs of density. Call it, if you will, the trade-off between good friction and bad friction.

The efficiencies were these:

- Density enables much lower consumption of resources and time.

- Density enables higher asset utilization.

- Density entails frequent physical interactions.

The costs were these:

- Density leads to a reliance on central systems.

- Density increases the need for courtesy and trust.

- Density requires coordination and negotiation.

This exercise isn't just a parlor game. What's useful about these good and bad frictions is that they represent a framework to explore how technologies might impact urban environments. This type of tool can guide technology firms hoping to responsibly deploy innovations in cities; otherwise, companies like Sidewalk can find themselves developing technology that is urban in application but doesn't make cities better. It's also helpful to policymakers working to protect the public interest because it can highlight what the long-term impacts of a given technology might be.

Before we tried to think about the future, we tested this framework against the past. Can it help us understand, for example, the last century and a half of American urban history?

Turns out it can.

The Principles of Density Past

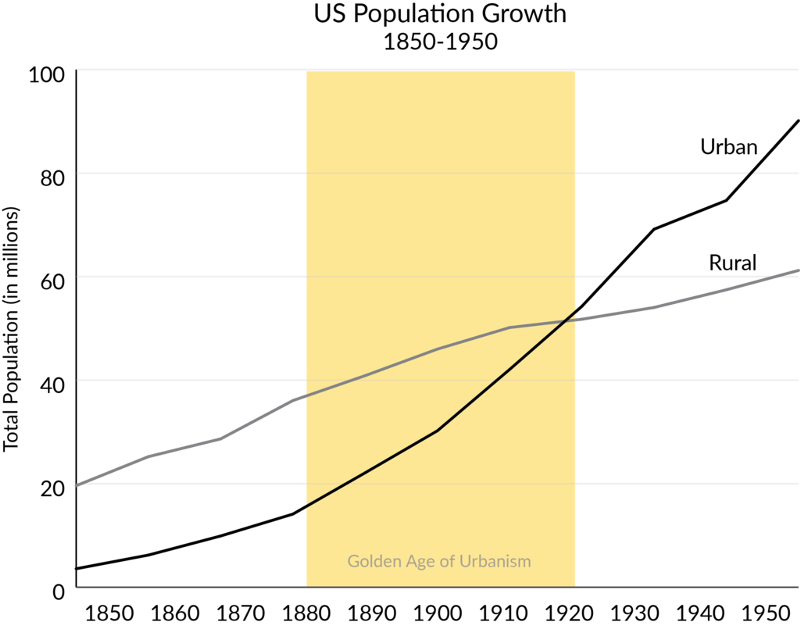

The greatest era of urbanization in America was between the 1880s and the 1920s, which historians label the Progressive Era. Using our first principles of density, we find that during this time, the efficiencies of density became far more valuable than they had been previously.

New forms of infrastructure — sewer systems, electric lines, streetcars, and the like — were expensive, so they could be built only where asset utilization was high. Compared to the overall cost of living, energy, and water were much larger expenses than they are today, so lower resource consumption was valuable. And for the most part, physical interactions were still required to share information.

At the same time, the costs of density declined dramatically. Managerial and technological advances made central systems much more efficient, in everything from supplying food to running transit systems. The biggest challenge around courtesy and trust at the time — namely, the spread of contagious disease — benefited from sewer systems, public health standards, and other improvements. And coordination costs in cities remained relatively low (for reasons that aren't worth celebrating): labor costs were low, and public input was minimal, so infrastructure could be built fairly quickly.

All in all, technology made the efficiencies of density hugely more powerful — and the costs way less so — than they had been before. As a result, cities grew dramatically.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

The middle of the 20th century saw the opposite trend.

As overall standards of living increased, resource efficiency became less valuable; this was the era when people talked about having electricity "too cheap to meter." As the federal government funded massive infrastructure investments, such as rural electrification and interstate highways, asset utilization declined in value. The proliferation of telephone, radio, and television reduced the need for in-person interactions to share news and do business, while cars made physical interaction on city streets far less desirable than during the pedestrian-streetcar-horse carriage days.

At the same time, the costs of density increased, though in many cases for good reasons. The unionization of public sector workers raised the costs of central systems even as it provided middle-class living to bus drivers and sanitation workers. The civil rights movement and the increase in non-European immigration made courtesy and trust something that had to be built rather than enforced through homogeneity and exclusion. And more effective local democracy, developed partly in reaction to the excesses of city-builders like Robert Moses, increased the consideration given to neighborhoods and the environment, though in doing so, it raised the coordination costs of getting things done in a dense setting.

As a result, the frictions of density became more intense, and the efficiencies of density became less valuable. And suburbs became the answer for millions of American families and companies.

I'd argue that the American urban renaissance of the last 20 years has seen a similar set of changes, often more economic than technological.

As infrastructure investments have declined, traffic congestion has extended far into the suburbs, making walkability, bikeability, and transit more attractive. Water shortages and climate change have made resource efficiency important again. The internet has reduced what I'd call "utility shopping," turning retail into a leisure activity in which a walkable environment is more attractive than a shopping center anchored around a parking lot. This shift, in turn, has increased the value of physical interactions, especially the unplanned interactions that drive creativity.

Concerns about trust — another safety word — have declined as inner cities have gotten safer over the last generation. And, like traffic congestion, the costs of coordination have extended into the suburbs, as NIMBYism has become as much a suburban as an urban phenomenon.

All of these trends, I would argue, have made density relatively more attractive, and encouraged Americans to return to the city.

The Principles of Density Future

So, what does the future hold? Of course, we can't know for sure. But our guesses right now go like this:

Overall, technology promises to make many of the efficiencies of density less valuable. Vehicle autonomy will reduce travel times and congestion, making the shorter distances of urban areas less valuable outside of the immediate, walkable neighborhood. And even though I've worked on urban climate change policy for more than a decade, I've become convinced that solar roofs, small-scale battery storage, and electric vehicles will soon make it more possible for suburbs to become more carbon-neutral than big cities, which can't generate as much clean energy onsite. (A smaller roof space-to-population ratio is yet another implication of density.)

Assets — from household appliances to utility networks — are likely to incorporate more and more technology, which will increase their costs. But at the same time, smarter construction techniques, including robotic construction, should be able to make construction cheaper, cleaner, and less disruptive.

Further, technology will make it easier to utilize assets well even in lower-density areas: not long ago, the only place in America that had truly plentiful, on-demand taxi service was Manhattan; today, TNCs have brought that kind of asset utilization to medium-density areas across the country.

Finally, we can assume that virtual reality and related technologies will reduce, although never eliminate, the need for physical interactions among people. Just as recorded music changed the nature of live performances, and Amazon changed the nature of shopping, I think we'll see the same phenomenon with working together and dining out: they will become more valuable but less frequent.

But technology also holds the promise of dramatically reducing the bad frictions of urban life. With big data, computer intelligence, and location tracking, we can imagine central systems that are far more efficient and offer far greater performance than they do today. It should be the case that transit becomes better and cheaper, that central utilities decline in cost, and that we can find ways to share or centralize new things ranging from power tools to dining rooms.

We also expect that technology can help increase trust and courtesy. We know the power of online reputation as a way to ensure good behavior among people who don't know each other. We know that data and computer vision enable huge leaps in security. But we can imagine things like using noise monitors to enforce nuisance ordinances, and even perhaps to cancel out noise, thereby reducing the number of complaints people have about their neighbors.

An Uber self-driving car cruises the streets of Pittsburgh in May 2016. Photo by Flickr user Foo Conner (CC BY 2.0).

And we know that technology can help reduce coordination costs. Online voting should enable more frequent consultations that reach a broader constituency than people who attend public hearings. Technology should enable us to negotiate space much more effectively: if we can move to a world of shared autonomous vehicles, we can virtually eliminate parking problems, a primary stated reason that many neighborhoods across the country oppose greater housing density.

So we've concluded that technology will make everything better. (Maybe I am learning to speak technology!) What it means is this: the key question is not whether it will change the efficiencies and costs of density, but which will change faster. Because what our framework tells us is that we are in a race. If the advantages of density decline faster than the costs of density decline, people will increasingly seek less dense neighborhoods. And if the reverse happens, we'll continue to see an urban renaissance.

A Call to Action for Urbanists and Technologists

So I'm left with two big implications.

The first is that technology will help make mid-density communities work better. As much as I am a loyal New Yorker, we don't need Manhattan levels of density to make great urbanism. It's actually at the lower levels of density where growth leads to the strongest pushback against further density. Traffic congestion, parking, fear of new neighbors, and other issues often conspire to turn otherwise thoughtful citizens into knee-jerk NIMBYs. So technology — especially the shared, autonomous vehicle — should make it easier to create mid-density, mixed-use developments, and to add moderate amounts of density to suburban areas.

That's a good implication because a lot more Americans will be interested in living in a medium-density neighborhood than a high-density one. The other implication, however, is more sobering.

As I look at the various things that technology can do to neutralize the benefits of density, I see a range of things that consumers will likely choose to adopt on their own: virtual reality, autonomous vehicles, and household solar power. Even when they take place in broader social or policy contexts, these are still individual decisions. That means the efficiencies of density will decline at the rate of consumer adoption and private-sector innovation. And that rate is typically very fast.

But the things that will make urban life easier are things that consumers cannot do on their own: incorporating technology into central systems like transit agencies, tackling the very real challenges of balancing privacy and security in public spaces, or developing tech-enabled approaches to public consultation. This means that the costs of density will decline at a rate that depends on the public sector. And that rate, often, is very slow.

That's the risk to cities from technology. It's not that AVs will lead to sprawl, or that virtual reality will keep people in their homes. The main risk is that urbanites will not move quickly enough to use technology to make it easier to live in cities. And that is what I have most clearly taken away from this thought experiment.

For a firm like Sidewalk Labs, and others working in urban tech, it should lead us to spend a little extra time on thinking about products and applications that can reduce the frictions of urban life.

But for urban policymakers, it should be a call to action. Because it means that the future of cities depends on how quickly the public sector can integrate technology, not on how quickly entrepreneurs and firms can innovate. Between 1880 and 1920 — that golden age of the American city — city officials were among the most aggressive, energetic, and tech-savvy members of society. They built water systems, sewer systems, streetcar networks, and electricity systems. They used public-private partnerships to build subways. They invented the public authority to build bridges. And they developed new forms of governance to manage it all, such as the council-manager system.

So it's not the case that the government is always slow or wrong. Just like it's not always the case that the private sector is always fast or right. But it is the case that digital technology can be good or bad for cities; which way it goes will depend not only on how quickly entrepreneurs innovate, or how quickly cities adopt technology, but on how well technologists and urbanists work together.

If we want cities to win the 21st century, it turns out we urbanists had all better learn to speak technology — soon. But it also turns out that if technologists want to make cities better, rather than just different, they need to learn to speak urbanism as well.

Top image: Density in San Francisco. Photo by Flickr user Tony Webster (CC BY 2.0).