Water Fronts: Planning For Resort and Residential Uses

PAS Report 118

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 118 | January 1959 |

Water Fronts: Planning For Resort and Residential Uses

Download original report (pdf)

Problems? On July 4 weekend, 150,000 persons visited the lake. Every weekend 8,000 persons visit a marina whose road from Highway 23 still isn't paved. Recreation areas that have been developed already are jammed on weekends. The Corps [of Engineers] said last week that 50,000 lots have been subdivided on the shoreline. Fifty thousand!

A horde of visitors every weekend jams highways leading to the lake. These people could be a great resource in tourist income and in summer residents, but only when facilities are available for them. Imagine what will happen with 50,000 lots and more, each containing a septic tank. There are no subdivision regulations. No regulations for septic tank installation, water, roads. Not a single county on the reservoir requires a building permit. Many of these lots — indeed thousands — are only 50 feet wide, and many of those are only 50 feet deep. Near Gainesville last week, several lots of 2,500 square feet on the lake sold for $1,000 each. Building codes now and subdivision regulations soon will help control that area within the city limits of Gainesville, but what about the remainder?

Sylvan Meyer, "Influence of Metropolitan Atlanta in the Upper Chattahoochee Valley Area," Sou'easter, August-September 1958, page 31

The situation described above is all too common in resort areas along river, lake, and ocean fronts as more people seek recreation away from home. The recreation boom is only one manifestation of the snowballing pressures on facilities building up in the United States and Canada from rapid population increases, higher family incomes, and more leisure time. The pressure on recreation facilities is dramatically apparent in metropolitan, state, and national parks, where such facilities as camp sites have become overcrowded. The pressure on private facilities has also mounted to the point where it behooves planning and other public officials to take an active interest in finding solutions to pressing problems in water resort areas.

Pressure on private facilities can be seen in every part of the country. One of the most common signs is the pre-emption of river bank, lake shore, and ocean front by private owners. The public is denied access to the once open beaches, fishing grounds, and boating areas. Another sign of the pressure of population plus leisure is the ease with which water frontage can be sold to private interests by land speculators. Land subdivision and development of private personal recreation space includes every type of development from summer cottage sites in the Michigan woods to the year-around Florida subdivision developments for those who want a house on a canal and a boat in the water, which also serves as a front yard.

These demands are met in two ways: through public recreation facilities, and through private investment in resorts. The simplest way is to increase public park space and facilities. However, an estimate of the demand for public and private recreation facilities in the year 2000, made by Resources for the Future1, is enough to make park officials quail. The report estimates that demand for "user-based" areas — "close enough to users to be enjoyed after school or work" — may be four times greater than at present. Demand for "intermediate" areas — "located within one or two hours' travel time" — may be 16 times greater than at present. Demand for "resource-based" areas — "offering opportunities for the finest outdoor enjoyment, but often not easily accessible to users except during vacations" — may be 40 times greater than at present. Accommodating increases of the order estimated will not be possible unless park facilities are increased much more than now seems likely. (The large expenditures needed to carry out a bigger park program will probably not be voted by state governments.)

On paper, acreage of municipal parks would have to go from the present total of around 3/4 million ... to around 6 million by the year 2000. State park acreage might have to go from the present 5 million to from 55 to 80 million. Quite clearly, much of the increased demand will take the form of heavier use of existing areas or heavier rates of use for new areas.

Even if the estimates are high, however, or if they must be modified by practical expediency, it seems clear that truly major increases in demand are in prospect; moreover, it seems highly probable that the presently more distant areas will experience a relatively far greater increase in future demand than will the closer and more easily used areas.2

Much of the demand for resort facilities in "the presently more distant areas" will have to be met through private development. The Resources for the Future report3 poses the question that planners need to answer: "how much of the estimated total increased recreation demand should be met from publicly provided areas and facilities, and how much can be supplied by private effort?" Private development of recreation areas needs more attention from planners: standards and controls are feeble, inadequate, and generally neglected.

Public park design and recreation standards, on the other hand, are widely known and reasonably adequate, although progress lags — primarily because of political and financial problems. But public agencies seem to be getting under way to meet the problems as far as they are able.

Every state now has some form of state park organization; the last two to organize, Arizona and Utah, created agencies in 1957. And before that, the National Park Service began its Mission 66 program — a park improvement program to be completed by 1966. It has also initiated a nationwide survey being made by the National Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission; and it offers assistance to state park agencies in planning the acquisition and development of state parks. In 1956, its publication, Our Vanishing Shoreline, alerted the nation to the few remaining opportunities to preserve frontage on the Atlantic Ocean for public use. Similar reports are to be published in 1959 and 1960 for the Pacific Ocean and the Great Lakes shore lines. These signs of activity are in contrast to the failure of local agencies to control private development in resort areas.

This failure of local planning agencies is pointed out by the Tennessee State Planning Commission in connection with the man-made lakes created by multi-purpose dam construction. Its report, Reservoir Shore Line Development in Tennessee,4 remarks that:

Much remains to be done before recreation opportunities made available by the reservoirs are fully grasped on the local level. It should be a function of local planning commissions to assess the recreation potential of the reservoirs and to translate this potential, as well as the recreation requirements of the people within their planning region, into a recreation land use plan.

One problem of private development that local agencies have failed to solve is pre-emption of waterfronts.

In the past, private provision of outdoor recreation usually has been undertaken through ownership and use of a specific tract by one person or family. This has often, through inclination or financial restraints, confined his activities to the one tract; and usually it has operated to exclude others from the use of the same areas.

There is another aspect of private development, however, that has concerned public officials as much as loss of public access: poor development of waterfront properties. Poor sanitary facilities, "deadening" of a resort because of poor subdivision design, mixed land uses, and inadequate road access should concern local and state authorities responsible for promotion of tourist trade. Conditions in many resort areas have deteriorated to the point that attention must be concentrated on restoring minimum standards to protect the public health; other planning problems have to take second priority.

This report deals with control of private development and use of water fronts for resort and residential purposes. In and near metropolitan areas, many water-front resort areas are being developed as year-around residential suburbs or are being engulfed by urban development so that resort characteristics are lost — while the problems remain. Examples are found in Seattle, which has a houseboat problem, and at White Bear Lake, Minnesota, where a former summer cottage colony has become a suburb of St. Paul.

LACK OF PLANNING IN RURAL RESORT AREAS

The lack of planning and regulation in rural resort areas is not due to failure of planners to solve resort problems. Instead, it is more often because there is no one to take action. Speaking of the inability of local governments to handle the mess around a United States Army Corps of Engineers' reservoir project in Georgia, a newspaperman6 said:

Planning people in metropolitan areas seem to me most naive in their attitude toward small cities and rural counties. Tactics that work in one place don't work in another. Remember that in what we call Lanierland, or the Upper Chattahoochee Valley, most of our counties have almost no leadership, absolutely no money and, indeed, little desire to change. If they see change coming, they hope it will wait or go its way without bothering them. I don't decry that philosophy: in fact, I often wish I could share it.

In one of our counties, a county with perhaps 100 miles of shoreline on Lake Lanier, live less than 3300 persons, less than 1000 families. There are perhaps a dozen or two college graduates in the county. There is no industry; a big industry is building there but few of its key personnel will even live in the county. There is almost no one to represent the county at development sessions, planning seminars or short courses. The commissioner's job is to see to roads; the legislator's job is to get from the state one road per term. A few men with imagination and ability despair of doing everything themselves, so they do almost nothing. Private capital for the development of attractive businesses, even the most meager tourist business, isn't available.

The example is extreme, of course. However, even in the Tennessee Valley region, which is the most progressive area in the country for rural and regional planning, a large percentage of rural governments have not been willing to assume responsibility for planning, zoning, or subdivision control. Several examples of situations needing correction are written up in Reservoir Shore Line Development in Tennessee, cited earlier.

Even urbanized New England has its problems. The Rhode Island Shore (published by the Rhode Island Development Council in 1956), points out the inability of towns to handle the mounting problems:

Consider the key figures in town administration and their educational and experience qualifications for their work. How many towns have a local building inspector, very often the key figure in any local planning program, who is a trained engineer capable of administering a modern building code incorporating performance standards? Does he understand the basic principles of modern zoning and the complex technical provisions now being incorporated into many new ordinances? Will his advice to the Town Council and the Zoning Board of Review be based on previous experience or on a knowledge of these principles?

Perhaps the most pointed examples of the difficulties of instituting planning and regulation in regions considered recreational are in the "cut-over areas" of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, which are all but ruined by successive logging operations.7 In those states many counties have never been fully zoned because each township is free to adopt the county zoning ordinance or not, as it chooses.

While the pioneer efforts and actual achievements of rural zoning in these areas should not be disparaged, it must be realized that in many counties enforcement has been only half-hearted at best and that a great deal of antagonism toward public regulation still exists.

One observer of the Wisconsin situation, G. Graham Waite, writing in the July 1958 issue of the Wisconsin Law Review ("The Dilemma of Water Recreation and a Suggested Solution") offers a rather daring solution to the problem of water recreation resources that faces up to the difficulties of getting adequate action from local governments. He suggests that the state manage all navigable waters in Wisconsin and also that it undertake a land use planning and zoning program in areas bordering on them.

To implement the land use planning portion of the "lake management" program, he suggests that the state government make a land use plan for the entire state. A governor's committee would then assume responsibility for making detailed land use proposals for each water recreation area. (A staff appointed by the committee would perform the work.) Once the land use plan had been adopted by the committee, the state itself would proceed to enact zoning ordinances for all local governments that had failed to adopt them. He recognizes that the state does not now have the authority to zone, but he develops a plea for state zoning:

Considering the number of governmental units now existent with authority to zone [that have failed to do so], it seems essential to the success of a comprehensive lake management plan that the state itself be given power to zone land along navigable watercourses to whatever use is deemed compatible with the complete lake management scheme. Lacking such authority, the difficulties of persuading the local authorities to zone in a manner consistent with the state's general plan would be grave indeed.... To afford the greatest opportunity for local participation in the management plan, efforts should be made to get the counties and towns themselves to adopt the zoning regulations worked out by the state personnel. Inducements to action along the desired lines would be provided through the knowledge that the state can act if the other authorities don't and, if a fair length of time were allowed the counties and towns in which to adopt the state's rules, through the opportunity afforded of working the state zones into the local plan. Finally, a grant of money to the local zoning authorities might be offered if they effected the desired zoning, the grant to be based on miles of shoreline involved and the costs of enforcing the regulation, and to be made periodically as long as the rules suggested by the state are enforced.

A recommendation for greater state support of local planning was made by the subcommittee on planning and land use of the Interstate Commission (New York-Vermont) on the Lake Champlain Basin.8 The subcommittee's report urges that the state legislatures enact enabling laws "so drawn as to powers and so implemented as to state appropriations that local governmental units are encouraged to initiate planning and zoning and can be financially assisted by state and federal funds during the early states of these efforts as sound community development."

The need for planning in resort areas has become a nationwide problem. Even the Great Plains states now have reservoir projects that have attracted resort development. The recreation seeker is penetrating into rural and wilderness areas that are totally unprepared to serve him and to guard themselves against land butchery. Some of the suggestions presented are probably unrealistic; that is to say, they are not possible in most states because rural interests either do not care about the problems or are actively opposed to the controls necessary to protect resort areas on either a statewide or local basis.

Virtually the only hope seems to be for state planning agencies, where they exist, and for interested development specialists within state governments to make common cause with planners in urging that rural resort areas at least be awakened to their problems and that local initiative be aroused.

It should also be noted that the existence of zoning bodies in rural areas does not mean that any planning is being done in those areas. Local zoning agencies need planning assistance from the state. And if the sometimes complicated problems of sanitation and public health are to be solved, competent sanitary engineering assistance will be needed to solve subdivision and development problems.

Those interested in planning should make a particular effort to get statutory authorization for powers of control over areas near public parks that are being developed. It is foolish to invest large sums in public park development only to have nearby private development ruin scenery, pollute the water, and intrude on public facilities. This type of program should be a minimum goal of public park and planning agencies.

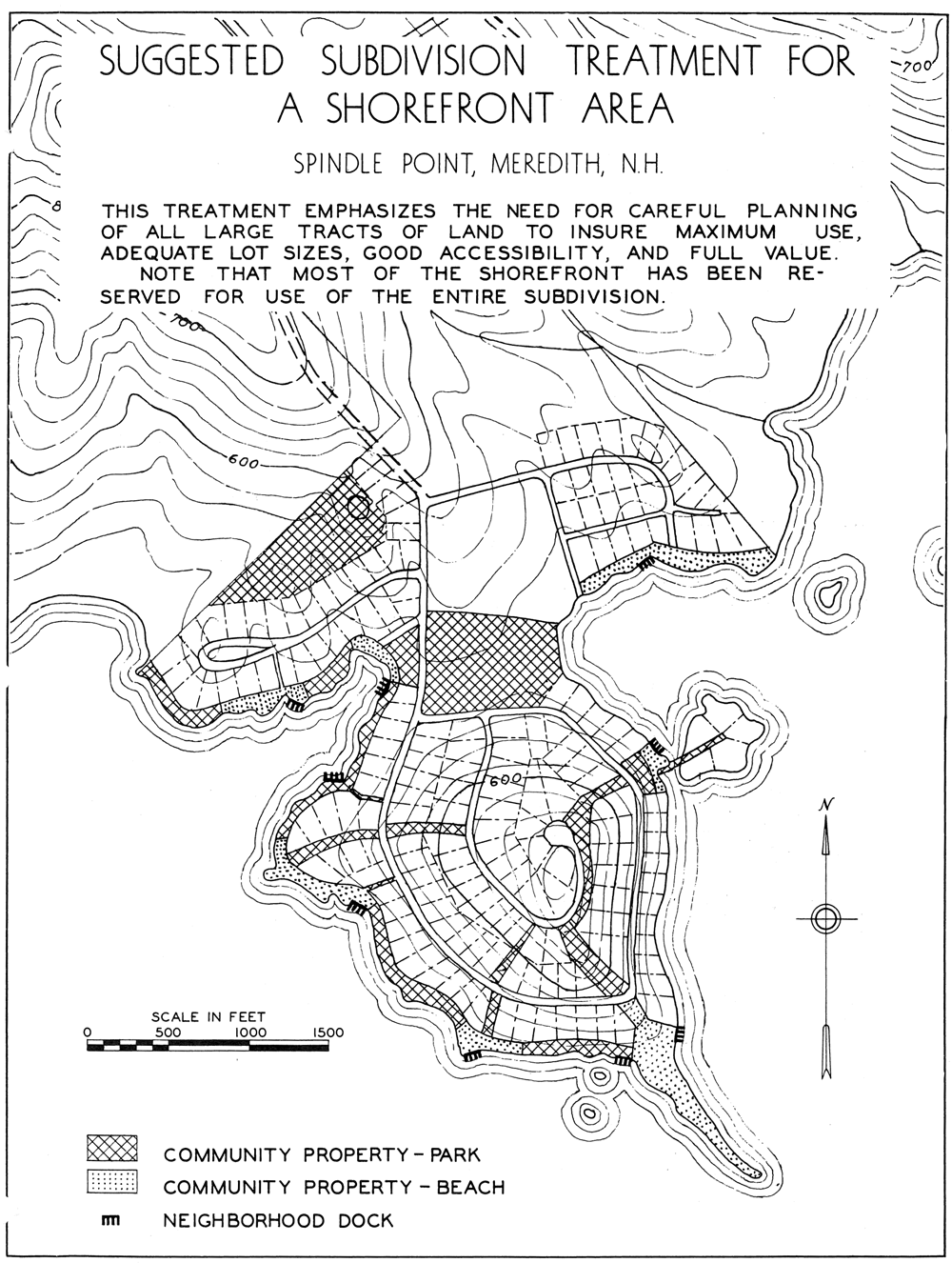

Figure 1. From A Study of the Lake Winnipesaukee Shore Line, New Hampshire State Planning and Development Commission.

PUBLIC ACCESS TO AND USE OF WATERS

Granted the demand for recreation facilities and public (largely state) action to provide additional park facilities, still a large part of the demand must be met in areas where much of the land is likely to be in private ownership. Public access through private land to waters open to public use (navigable waters as defined by statute) is one means of relieving recreation pressures. Access can be provided only by protection of existing ways and provision of additional means of access.

Some interesting doctrines appear in state laws dealing with the access question. Massachusetts has a rule of law reaching back to colonial times. Ponds with a surface of more than ten acres of water are called "great ponds." In colonial times, people were permitted to cross other people's property on foot in order to reach the "great pons" as long as they did not cross "corn or meadow land." However, today in Massachusetts access rights to great ponds have to be administratively determined and registered. Nonetheless, when street rights-of-way are established, the public can obtain access.

In Wisconsin9, access rights to some lakes may be restored if the existence of Indian trails can be established. Trails that were part of a portage route from lake to lake have great potential value as a recreation resource. Also, in Wisconsin a state law requires that certain classes of subdivisions provide public highways 60 feet wide to navigable waters at not more than one-half mile intervals along the shore.

One means of public access is through parks bordering navigable waters. Certainly additional park lands should be acquired along navigable waters to provide more public access. However, there are other means of providing access.

For example, the right-of-way of a public highway bordering a lake or river may touch the high water line. Since the high water line usually marks the limit of navigable waters, some simple form of facility, such as a fishing pier or outboard launching ramp, could be constructed within the highway right-of-way in order to facilitate public access.

The states and most municipal and county governments have the power to condemn land for a right-of-way to navigable waters. Also, federal and state agencies building multiple-purpose reservoir projects and other projects touching navigable waters often give other public agencies a chance to acquire water-front land that affords access. It is short sighted for a local or state government to turn down offers of suitable property from other governments. Full-fledged park development often is not needed to make the properties so acquired important parts of public recreation systems. Acquisition by condemnation or gift are probably the best ways of obtaining public access.

The problem of access to bodies of water is as much a problem to people who live near but not on water fronts as it is to the vacationer or weekender from the city. Shore lines have been so subdivided that owners of lots not directly on the water front have poor access or none at all. Around some bodies of water it is virtually impossible to find a place to launch so much as a canoe because access is cut off. In other instances, public access areas may be through marshes or over high bluffs. Perhaps no road has been built. And once access is denied to the water front, land away from the water loses value.

It has been pointed out in many studies that resort areas in which public access and opportunities for development away from the water front are provided realize greater income from commercial interests serving the area because more people can be accommodated. However, there are many subtle distinctions and more examples of competition and conflict between groups in water-front areas than have been discussed so far.

Competition

In general, the following groups compete for access to and use of water resources: owners of summer homes on or near the water; resort operators (owners of hotels, motels, trailer camps, and tent colonies); tourists and vacationers who want to use the water for fishing, water sports, boating, swimming, hunting, and want to preserve it for scenic purposes; farmers who want water for irrigation; industrialists who use water for many purposes, including waste disposal; and local governments that pipe it and use it for sewage disposal.

Though in this report we are not directly concerned with competition between recreation and nonrecreation users of water fronts, it should be noted that this conflict does exist in many areas. On some of the TVA lakes, for instance, there is competition for water-front lands between public recreation agencies, private home owners, and industry. Certain nonrecreational land uses may deserve first priority in allocating water-front lands. For example, it cannot be underscored too forcefully that sites suitable and needed for industry should be protected against pre-emption by land uses that can as readily be accommodated elsewhere. Municipal Waterfronts, PLANNING ADVISORY SERVICE Information Report No. 45, pointed out the high priority that industries that need to be on the water should have.

In deciding which of the would-be recreational users should be allowed water-front areas, the lines of battle are most often clearly drawn between riparian and nonriparian land owners. However, there are also other groups with opposing interests. For example, the fisherman objects to motorboat races and the cottage owner opposes the owner of a resort or children's camp. If the pressure on recreation facilities is to be alleviated, some conflicting users of water and water fronts will have to be segregated, and others will have to be reconciled, even though they appear incompatible at close range.

LAND USE PLANNING FOR WATERFRONT RESORTS

State, Regional, and County Levels

In at least three states, the state government has taken the first step toward planning for recreation and resort development. Although the emphasis in reports from California, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island is different, each furnishes background information with which planners could fit a resort area into a sensible statewide pattern of complementary types of resort development. The studies are:

Future Population, Economic and Recreation Development of California's Northeastern Counties. (Sacramento: Department of Water Resources, 1957) Pacific Planning and Research, Consultants. 28 pp.

Report of an Inventory and Plan for Development of the Natural Resources of Massachusetts, Part II — Public Outdoor Recreation 1957. (Boston: Department of Natural Resources, 1958) Edwards, Kelcey and Beck, Consultants. 174 pp.

The Rhode Island Shore — A Regional Guide Plan Study 1955–1970. (Providence: Rhode Island Development Council, 1957) 119 pp.

The methodology used in the Massachusetts and California reports can be of use to planners in other states undertaking similar studies.

Planners interested in studying recreation and resort development as part of the economic base in areas of county or township size may find useful the article by George S. Wehrwein and Hugh A. Johnson in the Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics for May 1943 called "A Recreation Livelihood Area." Similar studies were also made for states by several state planning agencies during the thirties.

In the March 1955 issue of Community Planning Review (Community Planning Association of Canada), there is an article by Harold A. Wood, "Recreational Land Use Planning in the St. Lawrence Seaway Area, Ontario," that describes Canadian efforts to establish a balance between public and private needs and recreational and nonrecreational demands for the new shore line created by the Seaway project. Many of the problems of the seaway shore line are similar to those of other reservoir projects.

It may be that small bodies of water should be used by only one type of vacationer. On larger bodies, perhaps the shore line should be divided among users with various interests and water areas should be allocated to particular groups in keeping with local conditions. This principle has been recognized and explained with great clarity in studies on plans for state parks.10 Because these studies frequently deal with how to handle existing and potential private development, as well as public park improvements, they are of interest.

Many communities that do not now think of themselves as water-front resorts should consider shoreline development as a means of attracting tourist income, as well as a way of providing recreation facilities for their own residents. Imaginative schemes for developing facilities for boating, fishing, wildlife study, swimming, golfing, commercial entertainment, and recreation in general are described and pictured in three studies.11 These studies emphasize the need for cooperation between private and public developers. The Oakland study covers a project that would enhance the water front by redeveloping a deteriorating area for commercial entertainment, shops, and restaurants.

In the Santa Clara County study the primary emphasis is on boating facilities on San Francisco Bay, with provision for other attractions, such as golf courses and commercial amusements, that would draw vacationists. Facilities for housing visitors would include motels, camps, and resort type hotels. A community of seaside houses on the Florida pattern — along finger piers and each house with its own boat dock — is also called for.

A similar type of development on Lake Erie is proposed for Lake County, Ohio. A combination of public regional park facilities and private development would provide boating, swimming, amusements, picnicking, camping, and nature study. Motels and camp sites are proposed to house visitors.

Allocating Land Uses

In allocating land to different groups of people seeking recreation it should be recognized that there are two important principles.

One — even if the shore area is primarily privately owned, access to the water should, in most cases, be provided for nonriparian land owners because public parks and recreation facilities with water fronts will not be available in adequate amounts to handle the growing demand. Access need not be exclusively public. A beach; park; marina, boat launching area or boat livery; yacht club; resort; camp; or hunting and fishing club that is privately owned but open to the public for a fee does, and must in the future, serve a large part of the public demand.

Two — much of the area around lakes, rivers, and oceans should be developed for recreation or tourist uses — motels, restaurants, trailer camps — to make the most of the economic base of the area. The recreation related portion of the economic base of an area can be preserved and expanded only if development for some distance behind the water front is encouraged. To accomplish this, the first principle — access for property owners who live away from the shore and or tourists — must be established and maintained.

Rural Resorts

Although many recreation and residential uses of water fronts have been mentioned, it may be helpful to give a more complete list, which may be useful in pointing up the diverse uses that must be reconciled to each other.

Summer cottages or residences (some owner occupied, others rented)

Year-around residences

Summer resorts (hotels, motels, cabins, boarding houses)

Hunting, fishing, gun, and riding clubs (in wilderness areas)

Combination resorts and hunting camps

Boys' and girls' camps

Golf courses

Beaches (public, private, and commercial)

Marinas, boat liveries, and boat launching ramps

Recreation clubs (yacht, boat, beach, golf, country)

Amusement parks

Tent colonies and auto trailer camps

Institutionally owned facilities (unions, churches, fraternal)

The basic land use is summer residences or cottages in rural areas or year-around residences in urban areas. On most water fronts devoted to recreational use, the summer residence occupies the largest proportion of land — often more land than for all other uses combined. Summer or year-around residences, therefore, probably are the starting point for determining the other uses that should be grouped with them.

Although each body of water should be considered on an individual basis — in the light of regional needs, present character of development, and natural suitability for various uses — the generalization can be made that a substantial portion of the water front should not be subdivided for residential purposes. Use of the water itself and part of the water front should be reserved for the public.

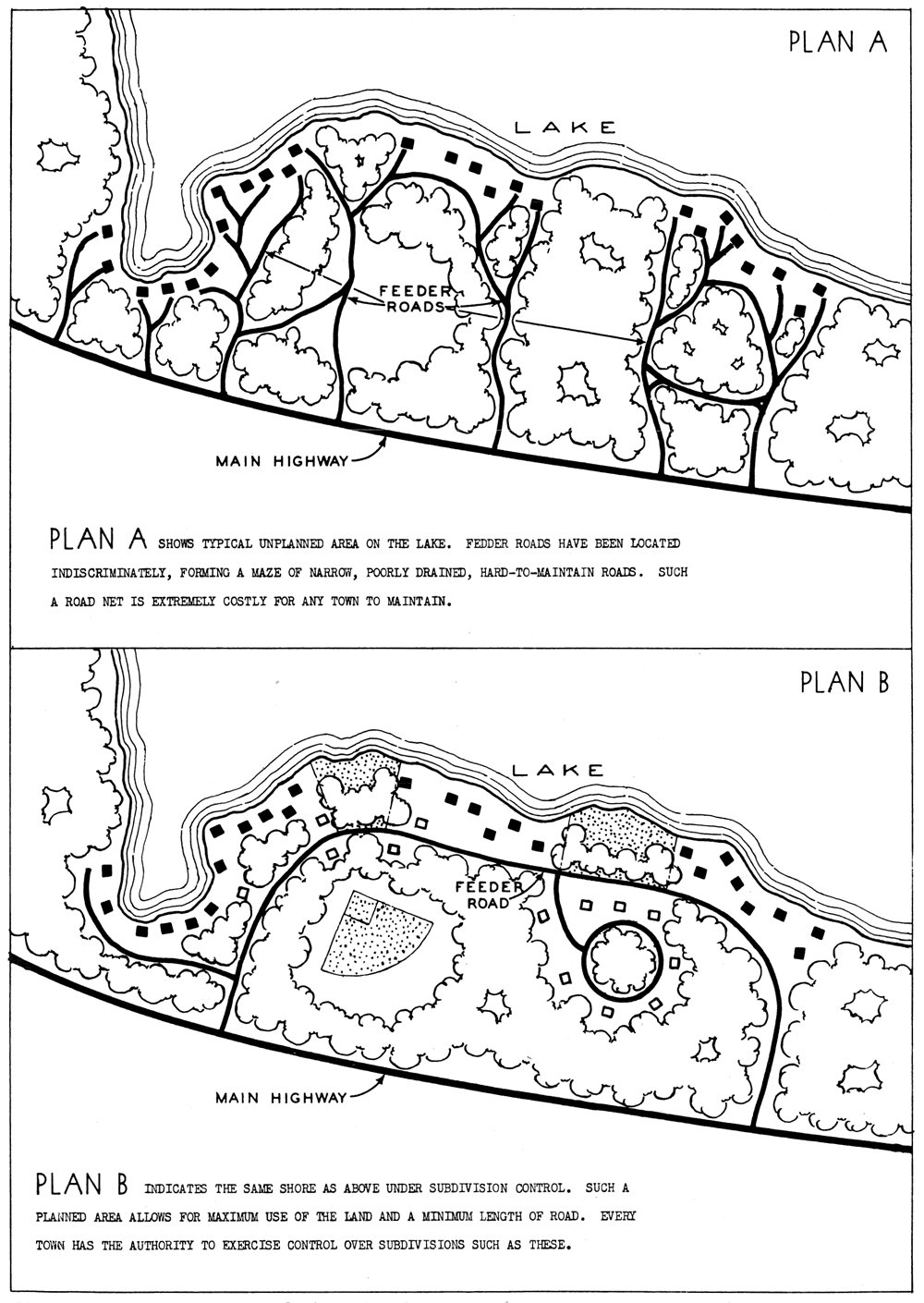

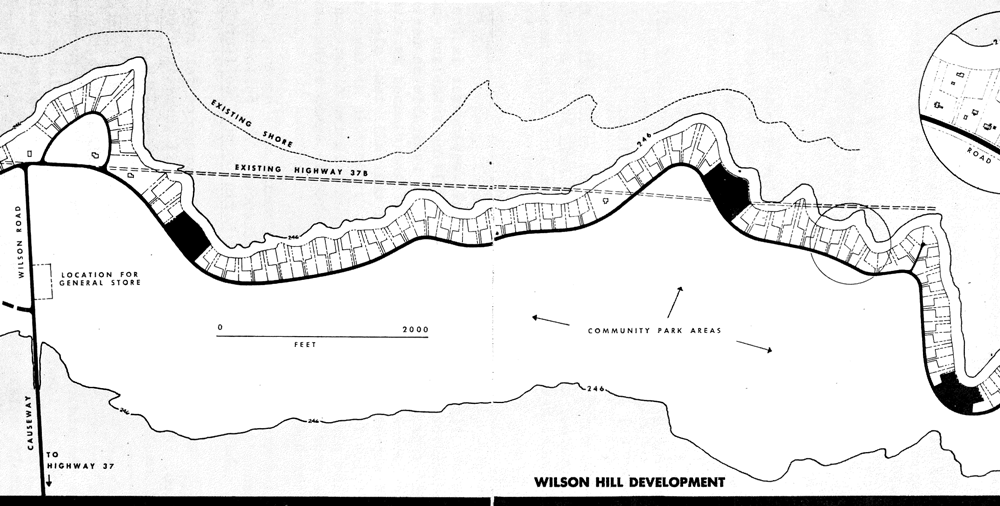

When easily accessible water frontage is reserved for the public, cottage and recreational or commercial development inland is encouraged. Different ways in which this may be achieved are shown in drawings (Figures 1 through 5) taken from reports of several public agencies that have explored the development possibilities of land under their control. The site plans for summer cottage development show several imaginative ways to provide access. It should be noted that some of the schemes make use of rights-of-way that would not be adequate for urban subdivision design but probably are suitable for summer cottage development.

Other uses that might be permitted in the same area with summer residences are hotels, motels, cabins, and boarding houses; clubs of many types including yacht, beach, country, and hunting and fishing; tent colonies; trailer camps; and institutionally owned recreation facilities such as those owned by churches, unions, or fraternal groups.

Some of these uses are compatible only in rural areas; in urban areas, the intensity of use would make it necessary to segregate hotels, motels, and boarding houses, trailer camps, some types of clubs, and some institutional uses from residences that are occupied the year around.

A use that is similar to those above but that should be separated from them is youth camps. In a remote and wilderness atmosphere, summer residents and resort vacationers object to the noise and activity in youth camps.

Agricultural uses should usually be excluded from vacation areas close to a waterfront. Clearing trees to create farmland breaks the vistas and the sense of privacy desired in resort areas around lakes, Agricultural pursuits also involve activities such as use of mechanical equipment for cultivation and harvesting or keeping of farm animals that are objectionable to resort visitors. Land erosion that causes siltation of bodies of water, pollution of water from farm wastes, and fire hazards are additional drawbacks to having agricultural uses near resorts.

A resort area should have various types of landscape (wilderness to cultivated lawns) and different land uses (housing to commercial amusements) if it is to appeal to a wide variety of people. And farms can be an important part of the recreation picture when used as summer homes or for lodging vacationers.

Among the necessary or suitable commercial uses in resort areas are the recreational uses listed previously (beaches, marinas, amusement parks, and others) and retail and service businesses such as restaurants, gas stations, food stores, gift shops, dance pavilions, movie theaters, drive-in snack bars, lumber yards, beauty and barber shops. Water-front locations are needed for the recreational uses named first (although the width of frontage need not be great in comparison to depth).

The commercial establishments that service the recreation industry and the tourists do not need water-front locations (although they may benefit by fairly close proximity). Service uses should be easily reached from the major access routes to the water front.

Two features of water fronts that have not been used to their best advantage are bluffs and marshes. Bluffs can be appropriately used for residential, park, or resort development because the views from the bluffs make such land desirable. Swamp and marsh lands provide desirable and necessary wilderness features that are also suitable for wildlife reserves or hunting areas.

In many new resort areas the motel is replacing the complex of summer hotels, rooming houses, and cottages. An example of the two types of resort developments side-by-side can be seen at Ocean City, Maryland. There the older area has a beach, boardwalk, carnival type amusements, and frame buildings. It is flanked up the oceanfront by new motels with swimming pools, as well as beaches, drive-in restaurants, and patches of open land held for the "right" price. Many of the large motels have restaurants with a nightclub atmosphere.

The motel type resort needs special treatment to insure that parking problems are well handled (many have asphalt "front yards") and to obtain sufficient yard space and landscaping so that the area retains its attractiveness. High design standards should be maintained in such areas. Because such developments tend to string out along highways, it is important that the buildings be attractive from the highway, as well as afford the guests a view of the water.

It must be admitted, however, that in many of these areas, it is already too late for regulation: they are irrevocably committed to ugliness and blight.

Resort Cities

Planning for the resort city, such as Asbury Park, New Jersey, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, or Petoskey, Michigan, involves special problems but also calls for the same basic techniques of land use planning that are applied to other cities. The principal differences are the large areas that have only seasonal occupancy and recreational uses; the periodic increases in population and traffic caused by the influx of visitors; and the concentrated impact of vacationists on the water-front areas.

Older resort cities are having problems of building deterioration, traffic jams, parking space, and overcrowded beaches and recreation facilities. In many of these older resorts the community has lost its desirability, largely because they are old. The income level of visitors is dropping. Plagued by inadequate parking at the beach front, where visitors want to leave their cars while they swim, walk the promenade, or use the commercial amusements, the hotels, rooming houses, and cottages at a distance from the beach lose trade. Blight comes in the form of building deterioration and mixed land uses. Traffic jams on roads leading to and along the water front force some visitors elsewhere. To regain its attractiveness, the older resort city can probably look only to renewal, to drastic rehabilitation, or to clearance and redevelopment.

Some old resort areas are faced with the problem of what to do with large mansions built in the era in which wealthy families vacationed in their summer homes and before traveling for a holiday became fashionable. Successful conversion to rooming houses or to other uses, such as a resort hotel for labor union members, is difficult. There is a real need for redevelopment of such areas that no longer can be used because of changes in vacation habits.

More than the rural resort, the resort city needs to be concerned with furnishing public open space, protecting access to the waterfront, and encouraging improvement of existing development. Land for public parks and recreation facilities and additional parking space might be provided through redevelopment in the deteriorated areas of the old resort city. The attractiveness of business areas should be considered too. Besides provision of parking space, programs for store front modernization, rerouting of traffic, and conversion of streets into pedestrian malls might be considered for revitalizing shopping districts.

Land use planning for resort areas calls for no new principles. However, the planning agency dealing with them needs to be ever aware of the conflicting demands for access to and use of water frontage.

Part of the planning agency's effort in a resort city should be to encourage development of the area near the water front that can profitably be developed for recreation related uses and thus accommodate more recreation seekers. Older resorts need determined and positive efforts to protect or recapture the attractiveness of the area. Especially in the older and more densely developed resorts, a downhill trend can probably be fought only through redevelopment. Water-front communities that have no resort development should consider stimulating private and public interests into cooperative development to cash in on the recreation boom.

ZONING FOR WATERFRONT USES

Zoning is the obvious answer to the problem of how to separate or combine the uses that have been discussed. Even though zoning for recreational facilities in water-front areas has not received much attention in ordinances or in planning literature, a few broad planning and zoning principles can be set down to deal with resorts.

Figure 2. From A Plan for the Development of the State Property at Pawtuckaway Lake, New Hampshire State Planning and Development Commission

The Vilas County, Wisconsin ordinance (amended to 1948) is an example of early rural zoning (1933) for recreation. While the primary concern of early county zoning agencies in the cut-over lands of northern Wisconsin was to control land settlement, the benefits of zoning have led to the adoption of refinements to rural zoning ordinances. In the Vilas County ordinance, under provisions for district 3, called "Commercial Recreation District," is an amendment in which the desirability of separating service commercial uses from other resort uses is recognized. The extracts below are provisions for the original recreation district (called "Forestry District") and the newer commercial recreation district.

SECTION II

District No. 1 — Forestry District

In the Forestry district no building, land or premises shall be used except for one or more of the following specified purposes:

- Production of forest products.

- Forest industries.

- Public and private parks, playgrounds, camp grounds and golf grounds.

- Recreational camps and resorts.

- Private summer cottages and service buildings.

- Hunting and fishing cabins.

- Trappers' cabins.

- Boat liveries.

- Minnow ponds and stands.

- Mines, quarries and gravel pits.

- Hydro-electric dams, power plants, flowage areas, transmission lines and sub-stations.

- Harvesting of any wild crop, such as marsh hay, ferns, moss, berries, tree fruits and tree seeds.

(Explanation — Any of the above uses are permitted in the Forestry District, and all other uses, including family dwellings, shall be prohibited.)

SECTION IV

District No. 3 —Commercial Recreation District

In the commercial Recreation District all buildings, lands or premises may be used for any of the purposes permitted in District No. 1, the Forestry District, and in addition, family dwellings, filling stations, garages, machine shops, restaurants, taverns, commercial stores, dance halls, theatres, and other establishments servicing the recreation industry are permitted.

(Explanation — Any of the above uses are permitted in the Commercial Recreation District and all other uses, including farms, shall be prohibited.)

It should be noted that certain uses that now are incompatible with recreation — production of forest products; forest industries; and mines, quarries, and gravel pits — are allowed. These uses are permitted because the original purpose of the Wisconsin ordinances was to prevent permanent settlement over wide areas without driving out the means of livelihood of the inhabitants. With the widespread growth of recreation as a source of income, the time has come when recreation should be protected by exclusion of uses that mar the landscape, such as commercial lumbering.

In other ordinances, conflicting uses have been separated. For example, the zoning ordinance for Chelan County, Washington (1948) permits the following uses in a recreational district: (1) public and private parks, playgrounds, camp grounds, golf courses; (2) public and private recreational camps and resorts; (3) hunting and fishing cabins; (4) private summer cottages and service buildings; (5) family dwellings for caretakers of resort properties, who give year-around protection.

The Chelan County ordinance has a forestry district to accommodate the wilderness "industries" permitted under the Vilas County ordinance.

In rural areas, three or four districts based on the resort and recreational land use groups discussed earlier should suffice to carry out a land use plan. Three districts are suggested in How to Make Rural Zoning Ordinances More Effective (University of Wisconsin Extension Service, 1957):

RESTRICTED recreational use districts along lakes and streams for private summer homes, hotel resorts and clubs.

COMMERCIAL recreational districts at a distance back from the valuable lakes and streams, for garages, filling stations, stores and other essential commercial establishments which service the recreation industry.

SPECIAL recreational districts for youth camps. This class of use district is being proposed in order to promote the calmness and quietness of a forest atmosphere in the restricted residential districts. There have been strong objections voiced to having youth camps located in areas with private residences and summer homes.

Three commercial districts are suggested in the Reelfoot Lake report. A "lake-front commercial" district is suggested for those commercial uses, such as marinas and fishing piers, that require waterfront sites. A "lake-oriented commercial" district would provide for commercial uses that are directly oriented to the lake but that do not require lake-front sites directly adjacent to the water. "Such activities include motels, restaurants, recreation supply and marine supply stores, etc. Effort should be made to maintain visual access to the lake from this land, in order to enhance its value."12 A third commercial zone, "general commercial," would contain other retail businesses associated with resort development.

Where the water-front area is in public ownership for parks, beaches, marinas, or other water-front recreation uses, the zoning problem is relatively simple. The area can be zoned as a residential district in which public recreation is a permitted use. In a zoning ordinance that has not been specifically written to provide for public recreation water-front uses, such residential zoning is a possible solution.

If an ordinance is to be amended to provide for a special purpose zone, the provision for the S-1 Shoreline District from the Huntington Beach, California ordinance (1946) can be used as an example:

S1 District — THE SHORELINE DISTRICT

The following provisions shall apply in the Shoreline District:

(a) Uses Permitted:

(1) Public recreation and public facilities therefor, including a public trailer camp and publicly controlled concessions in or on existing public buildings or structures or in said trailer camp, but no other uses.

(b) Buildings or Structures Permitted:

Only public buildings or structures necessary or convenient for recreational purposes or for beautification of the district.

Under such a provision, the burden of separating incompatible uses (marinas versus beaches, for instance) falls upon park designers and on park or recreation officials. They must carefully draw up contracts, deeds, and agreements for the private operation of concessions permitted on public land.

Zoning control of private water-front areas, on the other hand, requires thought. The first step should be to outline in nonlegal language the kind of development wanted. Many uses other than recreational can be made of private water-front land; private resort facilities include accommodations for transients and other residential, retail, marine, and amusement uses.

Special Purpose Districts

Special purpose zoning districts are justified to provide for logical uses of water-front land that in conventional situations would not be permitted in the same use district. For example, there is little need for much of the retail business normally associated with the usual commercial or business zone. However, certain commercial uses are needed along the waterfront to serve sportsmen and vacationists.

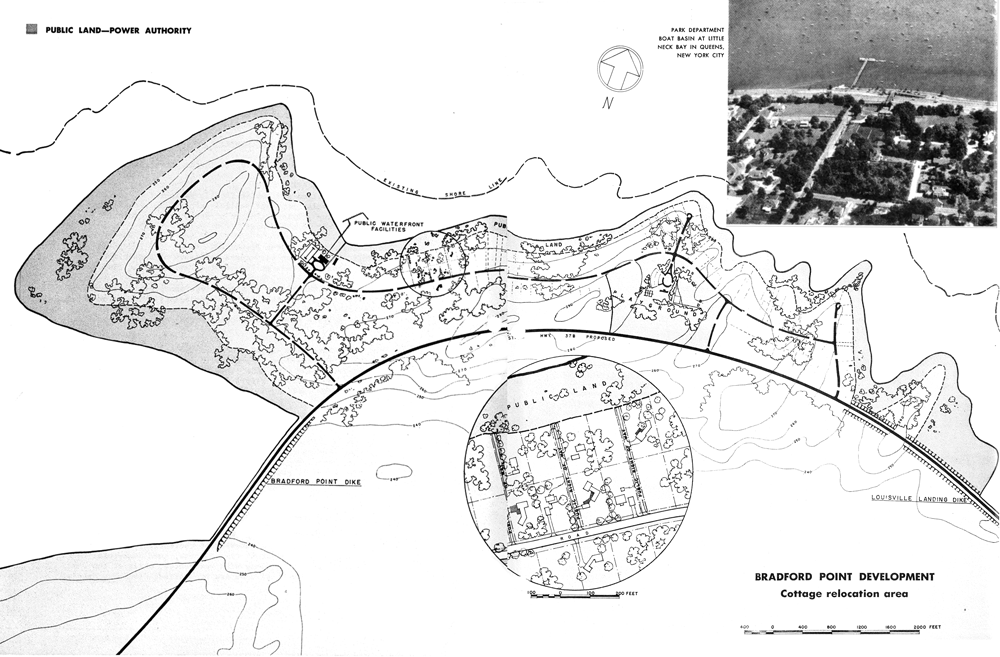

Figure 3. From St. Lawrence Power — Recreation, Housing, Highways, and Related Matters, Power Authority of the State of New York

The idea of special purpose districts for water-front recreation is sound. One of the many types is that in which residential and business uses are combined. They become compatible in deference to the predominant facility, activity, or purpose (in this case, water-front recreation) for which the district was designed. In water-front resort areas, some commercial recreation facilities can be permitted along with residences, while at the same time other commercial or industrial uses are prohibited. (See The Special District — A New Zoning Development (Information Report No. 34) for descriptions of other types of special districts.)

Depending on the pattern of development wanted, several special districts might be set up to separate or combine uses. Examples of how such uses might be grouped, taken from zoning ordinances, follow.

The zoning ordinance of Hamilton County, Ohio (1949) allows the following uses in a resort district:

Any use permitted in the "A" or "D" Residence Districts [single-family and multiple dwellings].

Summer homes and cabins, which need not front upon a street or place.

Bathing beaches and bath houses, but an approval of the location and treatment of these uses must be obtained from the County Health Department before a zoning certificate can be issued therefor.

Boat docks, private and commercial.

The selling or leasing of fishing equipment and bait.

Accessory buildings and uses customarily incident to any of the above uses, including the sale of food and refreshments.

To control possible nuisances from commercial facilities, the following conditions were suggested13 for commercial uses permitted by special permit on Tennessee reservoirs:

The applicant must own or control 1,000 feet of continuous shoreline parallel to the sailing line or the nine-foot navigation channel;

If the proposed location is on a tributary or in a cove, he must own or control the land on both sides of the cove or tributary unless same is more than 500 feet across at the proposed site. If more than 500 feet across, he must own 1,000 feet along one side of the cove, parallel to the sailing line or main channel of this tributary;

He must have 100-foot side yards between any permanent or floating structure and his side property line;

He must provide adequate parking space depending on the number of boat storage slips and boats for rent;

No recreational accessory use may be located on areas developed and designated as public access points by the Corps of Engineers.

Special districts that provide for only a few uses may be appropriate where complicated land use patterns are expected and where each use group should be separated because of incompatibility.

The examples that follow are taken from ordinances for urban municipalities. The provisions are for special purpose districts for water-front residences, for commercial amusements of the boardwalk-arcade type, and for water-front businesses.

Residential areas, especially of the Florida type might be provided for. The Seattle, Washington ordinance (1957) has an unusual RW residence water-front zone that is designed to provide for certain uses such as Florida-style waterway residences, yacht clubs, and houseboats.

RW — RESIDENCE WATERFRONT ZONE

Principal Uses Permitted Outright. The following USES:

(a) RS 500 PRINCIPAL USES permitted outright as specified and regulated in Article 8, except as modified in this Article.

(b) BUILDINGS and facilites for yacht or boat clubs which are incorporated, non-profit, fraternal organizations limited to pleasure boat and pleasure yachting activities and not including the public sale of alcoholic beverages on the premises, subject to the following conditions and restrictions and the requirements of the Building Code: [There follows a list of severe conditions on the structures and facilities that may be built by clubs.]

(c) Houseboats, subject to the following conditions:

- Minimum LOT AREA shall be two thousand (2000) square feet.

- The minimum distance between the sides or ends of adjacent houseboats shall be ten (10) feet.

- At least one side of each houseboat shall abut upon open water at least forty (40) feet wide and open continuously to navigable waters.

- For each houseboat there shall be provided one off-street parking space within a distance of six hundred (600) feet.

The "amusement-marine" or Coney Island type activities listed below are permitted as additional uses in water-front areas zoned C-3 commercial in the Santa Monica, California (1950) ordinance.

The following uses also shall be permitted if located in the "C3" district...:

-

Commercial amusements such as chute the chutes, ferris wheel, giant swing, merry-go-round, skating rink, and the like.

-

Exhibitions or games such as ball, knife, ring or dart throwing, shooting gallery, penny arcade, zoo, and the like.

-

Boat landings and wharves.

-

Boxing arena.

-

Fishing supplies, live or fresh bait.

-

Marine service station.

-

Motordrome.

-

Bathhouse or plunge.

-

Other uses similar to the above which are determined to be of an amusement-marine character...

Another group of uses might be those associated with boating, typified by the modern marina. The extract below is from the provisions for the water-front business district in the Warwick, Rhode Island ordinance (1957):

Businesses catering to marine activities such as commercial boat docks, boat service areas, marine equipment stores, boat storage and construction yards, boat repair facilities, bait and tackle shops, wholesale and retail fish and shellfish sales establishments, fish processing plants provided such plants comply with the provisions of Section 8.4, refreshment stands.

Marine oriented clubs.

Restaurants and motels serving the general public on approval by the Zoning Board of Review.

It is interesting to note that marinas today combine boat docks; boat services, including repair and storage; restaurants; boat sales; sales of fishing gear and food and other boating supplies such as gasoline and ice; accommodations for tourists and transients (often of the motel type); and sometimes a shopping center.

In a zoning ordinance written for a conventional area, such an intermingling of uses would not be permitted, but under private development this combination of disparate uses is successfully handled. It may be necessary to provide in the ordinance for a flexible special permit procedure if large-scale water-front development under single ownership is contemplated.

Land Under Water

Zoning of land under water is another detail of regulation in resort areas that deserves consideration. There are a few questions that should be answered before drafting provisions to handle zoning of submerged lands:

Does the jurisdiction of the local government extend over all or part of the water to be zoned?

Does the zoning enabling statute authorize zoning of water areas?

Does state law on riparian rights affect what might be done through zoning?

The determination of zone boundaries over water areas, which are without convenient landmarks, can be tricky; and the problem becomes especially important if after a water area is zoned part of it becomes land created by fill.

Some of the difficulties are: (1) extension of boundary lines that intersect the shore line at an angle; (2) determining what boundary lines "perpendicular" to a curving shore line are; (3) what the shore line is (there are many terms, some more clearly defined and more acceptable legally than others); (4) deciding what "midway" in an irregularly shaped body of water is; and (5) insuring that all water areas in the jurisdiction are zoned by providing a means to decide how zone boundary lines will be continued if they intersect.

This problem has seldom come before appellate courts. However, in a 1958 lower court case involving the Rye, New York ordinance and map (Rye v. Boardman, 171 N.Y.S.2d 885, ZONING DIGEST Vol. 10, page 178 (N.Y. 1958)) the court held that land under water was not zoned, apparently because the map showed zones extending only to the water line.14 The editor of ZONING DIGEST noted:

It hardly seems necessary to recommend that all areas within a community be zoned if it is the intention of the community to exercise control over all lands, including land under water. There have been cases in which railroad land was held not to be zoned simply because the color or symbol used did not cover railroad land.

Clear indication on the zoning map that all bodies of water are in some zoning district is probably the best way to be sure that water-front areas are protected from intrusion of incompatible uses from the water as well as from the land.

The water area may be zoned into the same types of districts as those of the adjoining land. On a lake, for example, a large part might be zoned for the most restricted district, which might be for summer cottages (although construction of dwellings beyond the shore or an established bulkhead line obviously would be forbidden). Only a small part of the lake might be allocated to commercial uses, such as marinas or fishing piers that can extend out into the water to a pierhead line.

In some zoning ordinances the following methods of setting boundaries (which can be included by amendment to the ordinance text) are used: (1) projection of zone boundaries from the landward side into the water up to the pierhead, harbor, or other lines set at a distance from the shore; (2) projection of boundary lines into the water; (3) zoning the water by reference to the zoning of abutting land; and (4) using the shore line as the boundary of all zones (the water, therefore, remains unzoned unless specific districts are included on the map over water areas). These methods are used if map amendment is not feasible and provisions for them are often in the section of the ordinance clarifying zone boundaries (interpretation of district boundaries section).

The Seattle zoning ordinance (1957) has a provision for projection of zone boundaries to pierhead or harbor lines.

Unless otherwise referenced to established lines, points, or features, the zone boundary lines are the center lines of streets, public alleys, parkways, waterways, or railroad right-of-way lines or in the case of navigable waters, the pierhead or outer harbor lines. Where such pierhead or outer harbor lines are not established, then the zone boundary lines shall extend five hundred (500) feet from the natural shore line.

Projection of zone boundary lines into the water is explained in a proposed amendment to the zoning ordinance of St. Petersburg, Florida (1957), which says:

Where district boundaries run to but do not extend into water areas, they shall be considered to run into such water areas in a straight line continuing the prevailing direction of the boundary as it approached the water until they intersect other boundaries or the corporate limits of the city. Boundaries which run through watercourses, lakes, and other water areas shall be assumed to be located midway in such water areas unless otherwise indicated.

A third technique is to zone water areas by reference to the zoning of abutting land. If this method is used, the terms of the provision should apply to land created by fill after the water area is zoned. Some provisions of this type inadvertently do not.

The following from the Muskegon, Michigan ordinance (1952) is an example of a provision in which the shore line is used as the boundary of all zones:

Where a district boundary line is shown on the map to be the shore line of a lake or other body of water, such boundary shall be the water's edge as it exists at the time this ordinance becomes effective or as it may be changed at any future time due to change in water level or due to fill carried out under the limitations of law.

Figure 4. From A Study of the Lake Winnipesaukee Shore Line, New Hampshire State Planning and Development Commission, January 1959

In The Text of a Model Zoning Ordinance, with Commentary,15 the following provision is suggested: "Boundaries indicated as following shore lines shall be construed to follow such shore lines, and in the event of change in the shore line shall be construed as moving with the actual shore line."

When the shore line is used as a district boundary, the ordinance should explicitly define the term "shore line." Some terms dealing with land-water boundaries are more clearly understood and accepted by the courts than others. This caution is equally important for definitions in subdivision ordinances.

Shore Line Control on Public Projects

Control of land uses around reservoirs deserves a few words of caution. Both federal and state agencies in control of reservoirs have had many largely unanticipated demands for recreation sites along reservoir waterfronts. In some instances, the agencies have been relatively successful in coping with such pressures. However, several lessons can be learned from the more numerous failures. The primary defect has been failure to obtain and maintain control over the immediate shore line. The general counsel for the Power Authority of the State of New York, in a legal opinion published in the report Land Acquisition on the American Side for the St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Projects, 1955, says:

The only practical method of handling land acquisition is, except in unusual situations, to take fee title to the property taking line and reserve to the adjacent owner a right of access to the water and provide that his use of the property between the property taking line and water, including the building of access roads, docks and other structures, will be subject to permit from the Authority.

The general counsel supports his opinion by discussing the experiences of other public bodies:

For example, because of the large number and variety of claims with which it was beset, The Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario has abandoned its former policy of acquiring only easements in land. Claims based upon erosion were among the most numerous of the claims filed. In recent years Ontario Hydro has purchased fee title to all lands acquired by it and is following this practice in acquiring property for the St. Lawrence project. When the project is completed and a general appraisal has been made of the operating situation and all of the facts surrounding the condition of the project, Ontario Hydro will then grant revocable permits, including rights of access and the right to build fences, docks and boat houses.

Conversely, the Tennessee Valley Authority originally took title in fee simple exclusively, but yielded to pressure in recent years and has taken a considerable number of easements. This has caused untold amounts of trouble and in some cases it has been forced to pay for property twice, and in others to pay a sum more than twice the original amount which it would have been obliged to pay after the land had become the shore front of a lake.

Retention of shore-line control by the agencies developing multipurpose reservoirs is only one step needed to obtain the maximum benefit from such projects. There must also be a program of planning, zoning, and subdivision control to insure sound development around the reservoir. And park officials should cooperate with project officials and planning authorities in obtaining park sites.

Control of Roadside Developments

Concern over the failure of local governments to preserve and protect the natural features that attract tourist and vacation trade has been one reason for advocating zoning of roadside areas. Highway zoning is strongly urged in the Tennessee State Planning Commission report, Reservoir Shore Line Development in Tennessee, for example. Roadside control through highway zoning is particularly appropriate for the access routes leading to resort areas in rural and wilderness surrounding because it is resort traffic that stimulates roadside development.

The usefulness of highway zoning has not led to important attempts to use it. States have hung back and few local governments have adopted highway zoning unless they were already involved in areawide zoning. There does not seem to be any doubt that highway zoning is possible, however. Erling D. Solberg, in an article, "Roadside Zoning," in Land Acquisition and Control of Adjacent Areas (Bulletin 55 of the Highway Research Board, 1952), wrote:

Roadside chaos can be prevented by adequate zoning. However, because the benefits from roadside zoning are sometimes largely nonlocal, local action may lag. In such areas, new zoning techniques and agencies may have to be provided to achieve the desired goals.

In some states, financial support of local zoning agencies may be most effective. In others, roadside zoning by the state may be necessary. Or a combination of state and local zoning may be desirable. In devising new roadside zoning techniques, a number of leads may be found in the means used by state legislatures for influencing zoning regulations in unincorporated areas. These means range from permissive enabling legislation to zoning regulations imposed by the state.

Finally, to be effective, any roadside zoning plan, whether under state or local ordinance, must be understood and be accepted by the general public. The public must be convinced of its desirability and advantage: first, in order to get the initial plan adopted, and secondly, to secure support for its enforcement.

Another device for protecting scenery — purchase of development rights or scenic easements — has been used in Wisconsin resort areas. Many Wisconsin roadsides in the cut-over country are protected by such easements, obtained when tax delinquent land was sold by the counties. Farmers and others buying the land usually readily agreed to a covenant restricting the purchaser to using the roadside strips for agriculture or forestry. No commercial development or subdivision is allowed.

SUBDIVISION CONTROL

In rural resort areas (and in all too many urban areas), the problems of bad water supply, improper waste disposal, water pollution, and poor construction overshadow the problems of land use planning and zoning. Public health factors deserve first priority in planning programs for resort areas. It is unfortunate that many water-front recreation places are in areas in which planning is virtually unheard of.

Sewage Disposal the Most Pressing Problem

Sewage disposal is the big problem. Wastes must be better disposed of than they have been in the past if resort areas are to retain their attractiveness. The general assumption is that a septic tank will be used only a few months of the year and that after a long rest it will recover its ability to handle wastes effectively. However, as more people take vacations and weekends away from home throughout the year, cottages in some resort areas are being used for more than the two-or three-month summer season. This is especially true in some of the northern lake areas, which are now also centers for skiing, hunting, and other winter sports. In metropolitan areas, some summer cottages are being converted to year-around residences; and areas platted for summer cottage development have become full-scale residential developments, such as one along the north coast of New Jersey.

This trend raises a question about the advisability of permitting sewage disposal methods such as privies, cesspools, and septic tanks at all in resort areas.

It is more and more apparent that septic tank standards throughout the United States are not high enough and that the systems have been poorly installed. It has been said that the soil in more than half the United States fails to meet the septic tank requirements for depth, absence of drainage impediments, low water table, and percolation rates.16

Resort lots are sometimes as small as 50 by 50 feet or 50 by 100 feet,17 with the result that density in summer cottage areas approaches and often exceeds that of single-family areas in urbanized places. However, minimum lot sizes for resort areas probably should not be less than for those of urban fringe areas in which septic tanks are permitted.

In view of the observations of sanitary engineers on the difficulties of using septic tanks except under favorable soil conditions in fringe areas, caution should be observed in allowing them in summer cottage areas. The tendency to think of cottage colonies as rural land uses can mislead to the assumption that farm standards of sewage disposal are adequate.

Subdivision regulations for resort areas should follow those adopted for urban areas. For example, if septic tanks are allowed, adequate lot sizes should be required. A rule of thumb for the safe use of septic tanks is that the minimum lot size be at least 20,000 square feet. If soil, subsoil, and topography permit, a smaller area may be satisfactory. However, under unfavorable circumstances, even larger areas are needed.18 Such requirements are in sharp contrast to some 2,500 square-foot lots in unregulated areas.

Because soil conditions vary from region to region and even from lot to lot, some planning authorities favor the strict use of procedures to establish minimums for each lot, rather than use the same minimum lot size for the entire jurisdictional area. However, especially in rural areas where there are likely to be difficulties in effective administration, it seems more desirable to establish a safe minimum and be prepared to ask for larger lots in subdivisions where soil conditions call for them.

One special requirement for septic tanks that should be included in subdivision ordinances drawn up for water resort areas is the following for a setback from the water's edge (incorporated in the Washington state monograph on subdivision regulations):

Proposed subdivisions, where the average size lot is one acre or more and where the soil conditions have been found satisfactory by the town engineer, and health officer, septic tanks, or other methods of handling wastes shall be installed in accordance with the standards and under the supervision of the town engineer except where septic tanks are provided on lots facing or abutting a body of water, the developer in addition to the provisions herein contained, shall install the septic tank in the upland 100 feet from the meander line [of a stream]. Where septic tanks are provided, the minimum lot area for each septic tank system shall be specified in the deed of each of said lots, and said deed provisions shall be acceptable and approved by the town engineer.

Group Sewage Disposal Systems a Solution

Sewage disposal by group systems and plants (the package plant) is suggested as an appropriate solution for summer cottage colonies. Although there is still much to be learned about their design, most sanitary engineers think it is possible to design satisfactory group systems that will be relatively economical.19

If resort areas are to continue to develop at densities approaching those of single-family residential areas, group sewage disposal facilities should be substituted for individual disposal. When population density reaches 125 to 150 persons a square mile, public sewers should be required. Sanitary Engineering Division Paper 1616 (referred to earlier) suggests that "as a goal, sewers [should] be considered whenever the land is subdivided into tracts of less than one acre." One reason for these recommendations is the effect of mass use of septic tanks on soil capacity. Even though individual lot sizes may be adequate under other circumstances, the soil rather quickly loses its ability to handle effluent when several square miles are served by septic tanks. Even if the recommended standards are adjusted for summer cottages to account for seasonal use, some form of public or group sewage disposal system will often be needed. Only an investigation by competent sanitary engineers can determine at what point individual sewage disposal facilities are an acceptable substitute for group disposal.

Perhaps the most difficult problem in using small sewage disposal systems is not design or construction but operation and maintenance. (This is true, of course, wherever the package plant is used.20) In most cases, the system is not public property in the sense that a local unit of government operates it, Instead, either the developer or a property owners' association usually does. Operation by the developer may not be desirable, especially if he is the hit-and-run type who loses all interest in the development once he has sold most of the property. Property owners associations of the type suggested in The Community Builders Handbook of the Urban Land Institute for managing country clubs and swimming pools, for example, are probably the best way to keep small group sewage disposal systems in good operating condition. However, the property owners' corporation should have sufficient members to raise funds for competent personnel. Of course, if local government or a special district can be induced to take over such systems, this is preferable. In that event it is in the government's interest to control the design and construction of the system to make sure that the public is not paying heavy costs for maintenance, operation, and possible replacement of an improperly constructed system. If operation is in the hands of a public authority, the costs should certainly be met by the use of a sewer service charge, rather than by general taxation.

Subdivision regulations for resort areas should be written with these points in mind: requirements for water supply and sewage disposal should be as stringent as those for more urbanized areas; provision should be made for the ownership and maintenance of small group sewage disposal systems by property owners associations, local government, or special districts; and the design and construction of such systems should be carefully checked.

However, the adoption of subdivision regulations usually assumes there is a planning agency, which may be unrealistic for many resort areas. Therefore, it seems imperative that the states undertake sanitary regulation programs under which minimum sanitary standards for resort areas will be set up. Such programs should probably be similar to those in New York and Wisconsin, both of which control subdivisions through plat review — New York through the health department, Wisconsin through the planning, health, and highway agencies.

As with many other suggestions made in this report, the planner is urged to ask the state legislature for laws that will benefit the recreation and resort areas of his state, even though he may have no direct interest in those areas. People from his urban area do go to resorts for much of their recreation. And planners working in resort areas may find that putting responsibility on the state is the only way that essential controls can be exercised over residents and developers who oppose regulation.

Platting Waterfront Property Is Problem

Important though control of sanitary conditions is, it is not the only problem created by subdivision of water-front property. Questions of title to lands under water are common. Subdivision ordinance controls can prevent poor platting of water-front property.

The Bureau of Governmental Research and Services as the University of Washington has given attention to problems of water-front subdivision in two of its publications, Regulating Subdivisions, Information Bulletin No. 167, 1954, and Surveys, Subdivision and Platting, and Boundaries, Report No. 137, 1958. In the latter report, the authors give the following example of some of the platting problems:

The lands around a privately owned lake are subdivided into water-front lots with a right of way serving these lots on the landward side of same. The plat applicable thereto also has one or two, sixty foot wide rights of way leading to the lake. These rights of way on the plat are dedicated to the people. Apparently the lot lines stop on the shore of the lake, and the lake presumably is to be of common use to the lot owners. What rights to the area covered by lake water has each lot owner since he has access to the lake? How far can he commercialize his rights of access and the common usage of the lake waters, letting outsiders cross his land to the lake? What rights can the public ask and have because of their access over the sixty foot right of way to the lake? What happens if the lake is lowered or dried up?

The plat survey should be explicit in these matters of lot and water boundaries. The plat restrictions should be explicit as to common water usage....

Prospective buyers of lots should know what they are purchasing both with respect to the land as well as the rights of use of the water surface of the lake, since the lake must be used in common to some degree to be of value....

Covenants should be required to define riparian rights and those of other owners to use the water. If a subdivision borders on water that is considered navigable under state law and therefore the public has a right to use, a dedication of the water to public use should be required as a matter of clarification and notice to prospective purchasers.

In addition to the problems of platting (drawing property lines and establishing rights to access and usage through restrictions), the subdivision ordinance should include requirements for information on the design of the subdivision in addition to that required for conventional subdivisions. In Regulating Subdivisions, it is suggested that the following be added to the design section for subdivisions bordering navigable waters to which the public has rights of use:

A statement relating to the proposed development of the subdivision indicating requirements for land fill, if any, waterways, moorage, wharves, or other proposed improvements, together with a map showing the location of the shorelands or tidelands proposed to be subdivided, the inner harbor line, line of navigability, and the line of ordinary high water.

A statement indicating, and a map showing, the proposed method of providing ingress and egress to the uplands from the tidelands or shorelands.

Additional requirements are necessary on private bodies of water:

The proposed plat, subdivision, or dedication of lands contiguous to, or representing a portion of, or all of the frontage of a body of water in which navigability, inner harbor lines, and outer harbor lines have not been determined shall clearly show the following features and information in addition to the provisions herein contained in Section 6.e. thereof:

- A map shall be prepared showing the proposed meander line, which line shall be located 20 horizontal feet inland from the line of ordinary high water and shall be referenced to meander lines heretofore located.21

- A map shall be prepared showing the names of the owners of all inundated lands, and all uplands lying adjacent or contiguous to the land proposed to be platted, subdivided, or dedicated.

- A map shall be prepared showing the land use regulations of the zoning ordinance applicable to the land to be platted, subdivided, or dedicated, and the land lying adjacent and contiguous thereto.

- A map shall be prepared showing the proposed wharf or dock line beyond which no structures may be erected, together with a statement containing a proposed dedication and the restriction of the use of inundated lands and water lying beyond the wharf or dock line.

- A map shall be prepared showing the location of all proposed monuments which shall be erected at the intersection of all lot lines and the meander line.

- A map shall be prepared showing the building line for all structures, and the building line shall be established 40 horizontal feet upland from a median line of the meander line.

Control of Fills

An unusual aspect of water-front residential development is the growing number of subdivisions that are created by filling swampland and bays. When subdivisions are created by fill without navigable channels being provided for water access, the major concern of the planner is with the adequacy of the fill as support for the development that will take place. Competent engineering review is needed to assist the planner in making such judgments. In addition, the planner should be concerned with the effect on drainage and shore line erosion when fills are created in swamp areas and particularly in bays or other bodies of water.