Street Naming and House Numbering Systems

PAS Report 13

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 13 | April 1950 |

Street Naming and House Numbering Systems

Download original report (pdf)

"Though fog or night the scene encumbers,

Why don't all buildings show their numbers

On lintel, wall or door?

Why can't a house say good and plenty,

'Hey look at me! I'm Nineteen-twenty,

The joint you're looking for!'

"Why can't our thoroughfares, our highways,

Our squares, our streets, our parks, our byways,

Have signs where all can see?

'I'm Lincoln Place.' 'I'm Pershing Corner.'

'I'm Avenue Ignatius-Horner.'

'I'm Boulevard Legree.'

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

"So, dwellings, mansions, roadways, alleys,

As well as rivers, mountains, valleys

And hamlets near and far

Throughout this self-effacing nation,

We really want the information;

Please tell us who you are! "

— Arthur Guiterman

Problems of street naming and house numbering may confront planning commissions in relation to new subdivisions or new planned neighborhood developments or these problems may arise simply as a result from the difficulties that have come out of the accumulated inefficiencies of an outmoded system. PLANNING ADVISORY SERVICE has recently received a number of inquiries on this subject.

No one would advocate designing a city or a subdivision along certain lines merely because it would be easy for the visitor or the delivery truck to locate persons and buildings. A well-planned community, with well-grouped major uses and service facilities, and with efficient means of intercommunication, is the primary concern of planners. However, once a street plan has been adopted by a community, with major and minor streets laid out, with feeder streets, and residential streets, and through highways and heavy traffic bearers, designed each according to its function, facilitating the use of these streets follows naturally. In part, the general attitude towards street naming and house numbering might be compared to that towards calendar reform; everybody is in favor of the reform, but such reform does not have top priority.

Correct as this attitude may be, it is unwarranted to dismiss street naming and house numbering systems as unimportant. Since planning in part is directed to providing rationality and order in community life, and in making communities more efficient and convenient, ease in locating places and facilities within a community should be encouraged.

This need has been recognized by citizen associations as well as official agencies. For example, the City Club of Chicago was instrumental in dramatizing the importance of clarifying the city's muddled street system. The first major attempt to systematize Chicago's street names was done in 1895; in 1913 and 1936 further clarification took place. The Nashville Times and Nashville Banner conducted a newspaper campaign in 1940 to reorganize the Nashville, Tennessee, naming and numbering procedure. Citizen support led to the formation of a special Joint Standing Committee on Ordinances on the Nomenclature of Streets in Boston in 1879 to recommend changes in that historic city's street naming policies — the recommendations made by the Commission at this early date contain some of the same general recommendations made today.

General Arguments for Adopting a Street Naming and House Numbering System

Many arguments may be advanced to justify the need for special funds for a study of existing practices in a community, or to justify a street naming and house numbering reorganization ordinance:

- Unfavorable impression on visitors to the community if they have difficulty in finding places of interest and the businesses and persons they wish to see.

- Expense to delivery services in routing and rerouting packages.

- Difficulty in quick delivery of mail.

- Loss of letters and goods, wrongly addressed.

- Potential increase in traffic accidents by motorists intent on searching for correct address rather than on driving.

- Difficulty in training civic employees in knowledge of the city, and the resultant disappointment by residents and visitors in the caliber of these employees and the government in general.

- Subconscious feeling of estrangement toward community on the part of residents and visitors to the community.

- Difficulty in emergency fire, ambulance and doctor access to correct address.

- Difficulty in maintaining correct legal documents, such as those for licenses, vital statistics, deeds.

Agencies and Organizations that may be Helpful in Devising a Street Naming and House Numbering System

- The local post office.

- Local police department.

- A retailers' association or large department stores.

- Chamber of Commerce.

- Better business associations, businessmen's associations such as Kiwanis, Rotary, etc.

- Local Railway Express Company.

- Real estate board, local home builder's association, subdividers of large tracts, abstract firms.

- The local newspaper.

- Regional office of the Federal Housing Administration.

- Local civic groups.

- Local utility companies.

- Local medical society and health department.

It is assumed that the street department, the city engineer, the department of public works, will be among the most interested municipal officials.

Possible Objections to a New System

Objections may be raised to changing street names and house numbers. These generally come from those business or professional firms that feel a close identification of their activities with their street address. Objections are also raised, particularly in some of the older areas, if it is believed historic names will be discarded, and that the municipality will thus lose some of its individuality. Also, some persons object to change per se, believing that if a previous system worked at a previous time, it should not be altered. The section on court decisions in this report discusses whether individuals have rights in maintaining existing street names.

General Recommendations:

1. No duplication of names or numbers. It is preferable not to have differentiation by a suffix "street" or "avenue." For example, "Washington Street" and "Washington Avenue" can too easily be confused, since often "avenue" and "street" are synonymous in the public mind. In some communities "place" is used to indicate a minor street closely associated with a major street — for example, "St. Anne Place" might be located a half block from "St. Anne Street." The suffix differentiation "place" is more defensible than the former example, since "place" generally connotes a subsidiary street, and because it more unusual that the ordinary suffixes, "street" and "avenue."

2. Continuation of a street name. A street should have one name only and should have the same name throughout its entire length. If the street is not a through street but is broken by intervening land uses and is laid out in substantially the same location at a more distant point, the same name should be used on all of the "links."

In some communities, if a street jogs sharply, the portion of the street running in the different direction is given another name.

3. There should be base lines dividing the community into east, west, north and south sections. It is not imperative that the suffixes "east," "west," "north," and "south" be used if a continuous numbering system is used, and if there are not many through streets. However, if the numbers radiate from the base intersecting streets, and there are many through streets, it will be easier to have such suffixes.

4. Numbers on parallel streets should be comparable. If a parallel street does not originate at the same point as another street, the numbers should not begin with a low number but should begin with the same number on a parallel street measured from the base line.

5. Numbering should be uniform, based on street frontage. This should be done within blocks and between blocks.

6. Numbering should be consecutive.

7. Even numbers should always be on one side of the street, and odd on the other. Common practice is to place even numbers on the north and west sides of streets and odd numbers on the south and east sides of streets.

8. It is good practice to distinguish between size and importance of street, and direction of street, by terminology. For example, "street" might be used for east-west streets, and "avenue" for north-south streets, or vice-versa. Diagonal streets or heavy traffic bearers might be called "boulevard." State or federal routes might be called "highway." "Drive" might be used for scenic pleasure thoroughfares. Curvilinear streets might use "place," "road," "way," and "lane," etc. (The Committee on Terminology established by the American Society of Planning Officials may make recommendations for the use of these terms.)

Miscellaneous Considerations

Subdividers have found that there is greater "sales appeal" for houses on named streets, particularly if "romantic" names are used with suffices such as "place," "road," "lane," than on numbered streets. For example, the home purchaser prefers to live on "Rose Lane" than on "72nd Street."

Natural barriers such as a river or lake front, a ridge, etc., or man-created barriers such as railroad tracks, often are useful "basing points" for street naming systems and house numbering systems, if these barriers are outstanding and bear a suitable relationship to the growth of the town.

The heart of the central business district is a good "basing point" for such systems. There may be a shift in the location of the central business district at a later date, but such shift should not cause disruption of the street naming system.

Central business district retailers' associations may be very much interested in seeing that the street naming and house numbering system radiates from the central business district. For example, in Chicago, Western Avenue and Madison Street were selected as the base lines for dividing the city into quadrants. The business interests in "The Loop" objected and were influential in establishing State Street and Madison Street as the dividing lines, even though that meant that there would be virtually no north-east quadrant of the city, due to the curve in Lake Michigan in that area.

In many communities, particularly in the Midwest, streets were laid out by law on the U. S. section lines. In some of these communities; the applicable regulations pertaining to the establishment of a gridiron street pattern have never been repealed. There also may be legal obstacles in establishing curvilinear street patterns or "super blocks" as well as perhaps some local street department reluctance to spoiling a gridiron street naming and numbering system.

Subdividers of large tracts have advised that street names be distinctive within a subdivision so that even though a visitor cannot immediately find an address on a curvilinear street, or in a cul-de-sac, he can immediately identify it as to its general location.

When a new street naming and numbering system is put into effect, it should be done completely at one time and not piecemeal over a period of time.

Presidents, states, famous women, famous army and military heroes, trees, famous men, cities, are favorite street name choices. Descriptive names such as "Lake," "Main," "Church" are also common. Historical names are often selected.

Streets may have interesting names which are in no way related to actual conditions, for example, a River Street may not be near any water, a Crooked Street may be straight, a Southport Avenue may not be close to a port. In Chicago, a Garfield Boulevard terminates at Washington Park, and a Washington Boulevard runs through a Garfield Park. It is not easy to select names, particularly for large cities. It was reported that London had approximately 5,350 street names, Paris 1,628, New York 5,003, Philadelphia 1,914, Baltimore 3,923, Cleveland 2,199, Detroit 2,262, and Chicago 1,360.

Communities requiring the posting of numbers often specify the type of lettering, size of numbers, etc. (See the Tucson, Arizona proposed ordinance in this report.) Some communities purchase these numbers, and others require the property owner to furnish them. Some communities paint or stencil the house number on the curb as well as requiring it on the house door itself.

Examples of Street Naming and House Numbering Systems

Tulsa, Oklahoma, is based on a grid with the basic line Main Street running north and south and the Frisco tracks running east and west. All the streets east of Main are named in alphabetical order for cities of the United States situated east of the Mississippi — Boston, Cincinnati, Detroit, Elgin, etc.; while all those lying west of Maine are named for western cities — also in alphabetical order, such as Boulder, Cheyenne, Denver, etc. All the streets south of the Frisco tracks are named numerically in sequence — 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc., while those north of the tracks are named after prominent Indians or pioneer citizens and arranged alphabetically — Archer, Brady, Cameron, and others. In all parts of the city, the house numbers start with the even hundred at each corner.

M. C. Shibley, City Engineer for Tulsa, reported in the American City, March, 1938, that:

"One can see at a glance what a simple problem it is to reach any desired number from any other part of the city. Suppose, for example, one wishes to go to 615 Cincinnati. Everyone knows Main Street, which is one of the principal business streets of the city. Cincinnati is an eastern city, therefore he knows that Cincinnati Street is the second block east of main. All the streets that are named numerically lie south of the Frisco tracks. Therefore, he knows that house number 615 is in the southern part of the city between 6th and 7th streets. All the house numbers on streets running north of the tracks have the prefix of the letter "N," thus making a clear distinction between 615 and N. 615. . . . "

An example of a small city that recently renumbered and renamed its streets, is that of DeQuincy, Louisiana, population approximately, 5,000. The old street system gave each addition or sub-addition to the city a code number which formed part of the house number; the block number also formed part of the house number as did the relative location of the house on the block (or actual house number). Thus, a house located in a new subdivision, might have a house number such as 98562 although it was only one block distant from a house numbered 403. Also, under the old system, some streets had different names at different portions of their length, one street having three names. Ten streets had to be renamed, so that each would have the same name throughout its entire length.

After the revision, two streets were set up as basing points, Division Street running north and south, and Center Street running east and west. Now, all of the streets have a prefix designating north, east, south or west. At the point where Center and Division Streets intersect, and house numbers increase in size, the further the distance from these intersecting points. The streets are laid out in gridiron fashion.

Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, recently revised its street naming system: on the east side-of the bay, which is the larger area, all north-south streets were assigned numerical names, beginning with "First Avenue," and the east-west streets were given geographical names (mostly states), beginning with "Alabama Street" and proceeding geographically to "Utah Street." On the west side of the bay, the north-south streets were given the names of cities, alphabetically arranged, and the east-west streets are named after trees.

Oshkosh, Wisconsin, prepared a new address system in 1949 which specified that all north-south streets should be called "Street," all east-west streets should be called "Avenue," all diagonal streets should be called "Drives," and all unrelated dead-end streets should be called "Courts." Rhinelander is another Wisconsin city that has adopted a new street naming and numbering system.

Henderson, Tennessee, adopted a new property numbering system in 1949 in which a grid was used and where there was a bend in the street, the numbering was continued as though the street was straight. An ordinance to provide for a uniform system of numbering in Jefferson City, Tennessee was published in Community Planning in Tennessee, a 1942 report of the Tennessee State Planning Commission.

The street-naming system of the metropolitan area of a city should be linked to the central city. A good example of a coordinated street naming pattern is in the vicinity of Washington, D. C.

The northeast Maryland suburbs falling within the area of the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission adopted a street naming system in 1941, which is primarily a continuation of the street naming system of Washington, D. C. The base lines for the new system are North Capitol Street and East Capitol Street in Washington. These streets radiate north and east from the U. S. Capitol, and form the two inner boundaries of that city's northeast section. East from North Capitol are a series of numbered (north-south) streets which continue beyond the Washington, D. C. boundary into Maryland suburbs to numbers as high as 95th Avenue. North of East Capitol Street, the system consists of several zones of east-west streets arranged in alphabetical order. (1) A zone of streets named with letters of the alphabet, such as A Street, B Street, etc. (this is in Washington, D. C. only), (2) then alphabetized two-syllable names of famous Americans, such as Adams Street, and Bryant Street (this zone is located almost entirely in Washington, D. C., but some streets cross into Mount Rainier, Bladensburg, and Brentwood, Maryland.) (3) The next zone consists of alphabetized three-syllable names of famous Americans, such as Allison Street, Buchanan Street, etc., (these names are used in Northern Washington D. C., and in Hyattsville, Riverdale, and Edmonston, Maryland and vicinity.) (4) The next zone extending into Maryland contains the alphabetized names of colleges, Austin Road, Clemson Road, and so forth. (5) The next zone consists of alphabetized Indian names, such as Apache Street, Blackfoot Street, etc., and is in Maryland only.

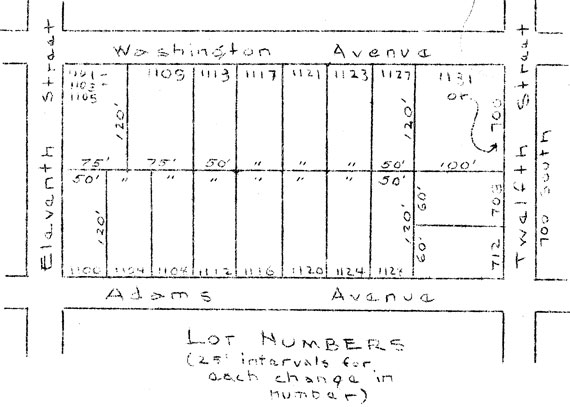

Monroe County, New York, at the request of the smaller municipalities within its area, undertook the job of eliminating duplication of street and road names, and of establishing a pattern of house numbering. Over two hundred duplicate names were discovered and eliminated. The new pattern was dovetailed into that previously established for Rochester, where numbers were formerly established on the basis of 15 feet per number. This was extended through the towns surrounding the central city, until all old subdivisions with lot frontages of less than 50 feet had been included. In the area of new subdivisions, where 50 foot lots have been required, the numbers were based on 50 feet intervals. Arterial highways originating in Rochester were given the same name for their entire length to the county line, and were given numbers on a continuous basis, the lower numbers nearer to the center of the town. Where incorporated villages had adopted another numbering system, the county numbering system was established so that the incorporated villages could join the county system when they chose to do so.

The Lyman or Salt Lake City System

The Lyman Uniform Street Numbering System was developed by Richard R. Lyman, a consulting civil engineer, and has been adopted by Salt Lake City and County, Utah, by St. George, Utah, and by Sacramento, California, among other cities, and was proposed by the Weber County-Ogden City Planning Commission. Some of the features of this plan have also been incorporated in Los Angeles, California and Kansas City, Missouri. This system utilizes a grid, with base line streets dividing the city into east, west, north and south portions. Streets are given numbers, instead of street names, with an increase in the size of the numbers, the greater the distance from the base lines.

Curved and crooked streets, and other streets deviating from the basic grid pattern may fit into this pattern of street numbering. For example, in the illustration used below, which appeared in the American City in the issue of September 1942, an irregular street will have as many "number" names as necessary. In the first example, the diagonal street from point A to point B, is considered as an east-west street and is called 624 North Street at one end, and 675 North Street at the other (since the street originates on the even numbered side on one block and runs through to the odd numbered side on the other end of the block, the numbers differ accordingly). The residents would choose as a street address whatever street name was closest to their home. If this street were to be continued in a diagonal direction, it would have a new numbered name at each intersection, corresponding to its geographic location. In the second example, a street running from points C to D to E would be in part an east-west street, and in part, a north-south street, and would be numbered accordingly.

House Rural Numbering

In rural communities, it is suggested that numbers be based on fractions of a mile, indicating the distance not only from the point of origin of the road, but also from other properties along that road. In a system described in the New York State Planning News of June 8, 1949, it is proposed that the house numbers indicate the hundredths of a mile the property is located from the origin of the road. This system is geared to the automobile and the speedometer, since a motorist may locate a property by watching his mileage gauge. The numbers begin at the end of the road nearest the city, village, or post office, or where the road joins a more important highway. There would be a hundred units to each mile or about 53 feet to a unit. Since odd numbers are used on one side of the road, and even on the other, there should actually be numbers running from 1–200 for the first mile. The way the system is reported in the article, only numbers 1–100 are applicable for the first mile, evidently assuming that the area will not be so built up to require use of all the numbers. In an article in the February 1950 American City, numbers 1–999 are used for each mile section of the road, and since odd numbers are on one side and even on the other, a number can be assigned to each 10-1/2 feet of frontage and can thus be carried through built-up communities as well as the rural areas. This is the system that has been adopted by Fresno County, California. A base point was established in the City of Fresno, which is located approximately in the center of the county, and north-south, and east-west lines established, with one mile square sections marked off in grid fashion. In an example given, an address 6238 West Rural Road could be located by consulting a directory for the location of the Rural Road, and the property would be located a little more than 6.2 miles west of the base line.

Street Naming and House Numbering in New Subdivisions

An example of street naming and house numbering in a modern subdivision with a curvilinear street pattern is that of Park Forest, Illinois. In Park Forest, the new community development south of Chicago, one of the designation problems involved making a decision as to which of two streets to use in giving the unit an address. The buildings — row houses — are grouped around parking bays, and the units actually face neither street. The sketch shows how this and some of the other numbering problems were handled.

Professor Eugene Van Cleef has described a system of house numbering on irregular streets, within a larger framework of a gridiron street pattern, in the February, 1950 issue of American City. A house derives its street address from its location in respect to the two nearest major arteries.

Pertinent Court Decisions

In the case of Hagerty v. Chicago, 195 N.E. 652 (Illinois) the court held that an ordinance changing the name or a street under statutory authority is not invalid as unreasonable. Under the Laws of 1911, the common council of cities, and the president and board of trustees in villages are expressly authorized to name and change the name of any street, avenue, alley, or other public place. The property owner abutting the street was found to have no property right in the name of the street which would prevent the municipality from changing the name of the street.

According to Bacon v. Miller, 160 N.E. 381 (New York) names of streets and numbers of houses may be changed since there is no vested right in the name of a street or in a number originally assigned. The court also found that although renaming and renumbering streets is inherently a local matter, it cannot be done arbitrarily, but must be done in good faith.

In Ohio, the court held that in Miller v. Cincinnati, 10 Ohio Dec. 423, 21 Cin. Law Bul. 121, if no good cause exists for changing the name of a street, the municipality cannot change it accept on petition of the abutting owners.

In Brown v. Topeka 74 P. (2d) 142, it was held that a city had the implied authority to change the name of a street.

However, when streets are deeded to a city or village, the deed conveying the street may restrict the grantee's right to change its name according to Belden v. Niagara Falls, 136 Misc. 406, 241 N.Y.S. 5.

Naming streets is a legislative act and not a judicial act, according to Darling v. Jersey City, 78 A. 10 (New Jersey), and is not subject to review by or interference from the courts. Also, in Eldridge v. Fawcett, 223 P. 1040 (Washington) it was found that the right to change the name of a street is a legislative right which is not exhausted by previous exercise thereof.

In Norwood Heights Improvement Association Inc., v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore et al., 72 A. (2d) 1, (Maryland, 1950), the Association appealed a decision of the Board of Municipal and Zoning Appeals, objecting, among other things, to the house numbers to be given to several apartment buildings. The court dismissed the appeal, and, among other things, stated that the zoning ordinance had nothing to do with the numbering of new houses.

Sample Ordinance

Model ordinances for establishing street naming and house numbering systems have been proposed by the League of South Dakota Municipalities, in its Bulletin of November, 1936, and by the League of Wisconsin Municipalities in The Municipality, February, 1941.

Tucson, Arizona, proposed a new system in 1949; the suggested ordinance is reproduced below to indicate types of provisions which may be included in such an ordinance.

"An Ordinance Establishing A Uniform System For Numbering Buildings And Streets, Naming Streets, Establishing Base Streets and Designations For Numbering And Naming Purposes, Providing The Methods For Instituting Said System, And For The Enforcement Thereof.

"The Mayor and Council of the City of Tucson do ordain as follows:

"SECTION 1. There is hereby established a uniform system for numbering buildings fronting on all streets, avenues, and public ways in the City of Tucson, and all houses and other buildings shall be numbered in accordance with the provisions of this ordinance.

"SECTION 2. Speedway shall constitute the base line for numbering buildings along all streets running northerly and southerly; and Pioneer Boulevard, as hereinafter named and established, shall constitute the base line for numbering buildings along all streets running easterly and westerly.

"( 1) Each building north of Speedway, and facing a street running in a northerly direction shall carry a number and address indicating its location north of said base street.

"(2) Each building south of Speedway, and facing a street running in a southerly direction shall carry a number and address indicating its location south of said base street.

"(3) Each building east of Pioneer Boulevard, and facing a street running in an easterly direction shall carry a number and address indicating its location east of said base street.

"(4) Each building west of Pioneer Boulevard, and facing a street running in a westerly direction shall carry a number and address indicating its location west of said base street.

"(5) All buildings on diagonal streets shall be numbered the same as buildings on northerly and southerly streets if the diagonal runs more from the north to the south, and the same rule shall apply on easterly and westerly streets if the diagonal runs more from the east to the west. All buildings on diagonal streets having a deviation of exactly forty-five (45) degrees, shall be numbered the same as buildings on northerly and southerly streets.

"SECTION 3. The numbering of buildings on each street shall begin at the base line. All numbers shall be assigned on the basis of one thousand (1000) numbers to each mile, or one thousand (1000) numbers between established section lines or the streets located thereon, and where practicable two numbers shall be assigned to each ten and fifty-six hundredths (10.56) feet of occupied frontage.

"SECTION 4.(a) All buildings on the right-hand side of each street running from the base street shall bear even numbers. All buildings on the left-hand side of each street running from the base street shall bear odd numbers.

"(b) Where any building has more than one entrance serving separate occupants, a separate number shall be assigned to each entrance serving a separate occupant providing said building occupies a lot, parcel, or tract having a frontage equal to 10.56' for each such entrance. If the building is not located on a lot, parcel, or tract which would permit the assignment of one number to each such entrance, numerals and letters shall be used, as set forth in Section 8 herein.

"SECTION 5. All buildings facing streets not extending through to the base line shall be assigned the same relative numbers as if the said street had extended to the said base line.

"SECTION 6. In addition to the numbers placed on each house or other building as heretofore provided, all streets, avenues, and other public ways within said city are hereby given numbers and directional symbols according to their distance and direction from the two base streets set forth in Section 2 herein.

"(a) All streets approximately parallel to and north of Speedway are given the direction North.

All streets approximately parallel to and south of Speedway are given the direction South.

All streets approximately parallel to and east of Pioneer Boulevard are given the direction East.

All streets approximately parallel to and west of Pioneer Boulevard are given the direction West.

"(b) East street shall bear a number or numbers corresponding with the one-tenth (1/10) of a mile in which said street is located at any given point. If said street is not parallel with either base street, then its number shall vary in the case of each address on said street according to the distance said address is from both base streets. Each house or other building in addition to the number or numbers given it under Section 4 herein shall also bear the number and direction of the street on which it is located.

"SECTION 7(a). The Mayor and Council shall cause the necessary survey to be made and completed within six (6) months from the date of the adoption of this ordinance and thereafter there shall be assigned to each house and other residential or commercial building located on any street, avenue, or public way in said city, its respective number under the uniform system provided for in this ordinance according to said survey. When the said survey shall have been completed and each house or building has been assigned its respective number or numbers; the owner, occupant, or agent shall place or cause to be placed upon each house or building controlled by him the number or numbers assigned under the uniform system as provided in this ordinance.

"(b) Such number or numbers shall be placed on existing buildings on or before the effective date of this ordinance, and within twenty (20) days after the assigning of the proper number in the case of numbers assigned after the effective date of this ordinance. The cost of the number or numbers shall be paid for by the property owner and may be procured either from the street superintendent at the unit price for the same, such price to be the cost of such units to the city, or from any other source. Replacement of numbers shall be procured and paid for by the owner. The numbers used shall be not less than three (3) inches in height and shall be made of a durable and clearly visible material. If the proper number is not placed on an existing building on or before the effective date of this ordinance, it shall be the duty of the superintendent of streets to install the proper number or numbers on said premises as hereinafter set forth, and to make a charge of five dollars ($5.00) for each number so installed; which said charge shall become a lien against the premises on which said building is located, and shall be added to the city real estate tax on said premises for the ensuing year.

"(c) The numbers shall be conspicuously placed immediately above, on, or at the side of the proper door of each building so that the number can be seen plainly from the street line. Whenever any building is situated more than fifty feet from the street line, near the walk, driveway, or common entrance to such building and upon a gate post, fence, tree, post, or other appropriate place so as to be easily discernible from the sidewalk.

"SECTION 8. Where only one number can be assigned to any house or building, the owner, occupant, or agent of such house or building, who shall desire distinctive numbers for the upper and lower portion of any house or building, or for any part of any such house or building fronting on any street; such owner, occupant, or agent shall use the suffix (A), (B), (C), etc. as may be required.

"SECTION 9. For the purpose of facilitating a correct numbering, a plat book of all streets, avenues, and public ways within the city showing the proper numbers of all houses or other buildings fronting upon all streets, avenues, or public ways shall be kept on file in the office of the city superintendent of streets. These plats shall be open to inspection of all persons during the office hours of the superintendent. Duplicate copies of such plats shall be furnished to the engineer and building inspector by the city superintendent of streets.

"SECTION 10. It shall be the duty of the city superintendent of streets to inform any party applying therefore of the number or numbers belonging to or embraced within the limits of any said lot or property as provided in this ordinance. In case of conflict as to the proper number to be assigned to any building, the said superintendent shall determine the number of such building.

"SECTION 11. Whenever any house, building, or structure shall be erected or located in the City of Tucson after the establishment of a uniform system of house and building numbering has been completed, in order to preserve the continuity and uniformity of numbers of the houses, buildings, and structures, it shall be the duty of the owner to procure the correct number or numbers as designated from the city superintendent of streets for the said property and to immediately fasten the said number or numbers so assigned upon said building as provided by this ordinance. No building permit shall be issued for any house, building, or structure until the owner has procured from the superintendent of streets the official number of the premises. Final approval of any structure erected, repaired, altered, or modified after the effective date of this ordinance shall be withheld by the city building inspector until permanent and proper numbers have been affixed to said structure.

"SECTION 12. There is hereby established a uniform system of street naming in the City of Tucson, and all streets, avenues, and other dedicated public ways shall be named in accordance with the provisions of this ordinance.

"(a) All streets and other public ways running in the same direction and having a deviation of not more than 125 feet, shall carry the same name unless special circumstances make such a plan impracticable or not feasible.

"(b) All through east and west streets shall carry the designation 'street' and all through north and south streets shall carry the designation 'avenue,' except for thoroughfares on section lines.

"(c) All through thoroughfares running north and south on section lines shall be designated as 'boulevards.'

"(d) All through thoroughfares running east and west on section lines shall be designated as 'ways,' such as Speedway, Broadway, etc.

"(e) That part of any street ending in a 'dead-end,' or cul-de-sac, shall carry the designation 'place.'

"(f) The name 'lane' shall be used in any residential or business development for any north and south alley street which bisects or crosses a nominal block or series of blocks, and the name 'row' for any such east and west alley street.

"(g) Any street or portion thereof, running in a straight line for more than 500 feet, which moves at an angle of more than 20 degrees from a true north-south or east-west pattern, shall be designated, wherever practicable, as 'stravenue.'

"(h) Any street which curves in an irregular pattern to an extent that its east-west or north-south direction is changed, shall be designated as 'paseo.'

"(i) A short street that does not continue through, running east and west, shall be designated as 'calle.' Such a short street running north and south shall be designated as 'via.'

"(j) No street established or named after the adoption of this ordinance shall bear a name in a language in conflict with its destination.

"(k) The Mayor and Council may adopt further designations or any additional rules and regulations which may be required from time to time upon recommendations of the Planning and Zoning Commission by amending this section.

"SECTION 13. For the purpose of clarifying and systematizing the present street naming pattern in the City of Tucson and to implement the application of the matters set forth in Section 12 herein, there is hereby adopted the following plan.

"(a) The Planning and Zoning Commission of said city is hereby authorized to prepare and present to the Mayor and Council a complete plan for the naming of all streets, avenues, and public ways within said city.

"(b) Said Planning and Zoning Commission shall follow the general plan set forth in Section 12 herein and such other rules as are herein set forth.

"(c) If said Commission shall find an existing street now carrying more than one name, it shall recommend that said street shall bear the name under which it currently travels the longest distance both inside and outside of the city limits of said city unless circumstances indicate that another and different name would be desirable. Said Commission if it sees fit, may hold public hearings at which interested property owners may express their views concerning the changing of the name or names of any street.

"(d) For the purpose of establishing a north and south base street, for numbering and naming purposes, the present existing north and south First Avenue and the extensions thereof is hereby named and designated as Pioneer Boulevard and is hereby established as the north and south base street for the purpose of this ordinance.

"(e) The north and south bound streets west of said Pioneer Boulevard, which are named Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, Eleventh, Twelfth, Thirteenth. Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth Avenues, are hereby renamed in a manner to be determined by the Mayor and Council upon recommendation of said Commission, so that the present conflict between numbered streets and numbered avenues is eliminated.

"SECTION 14. Every subdivision plat submitted to the Mayor and Council for their approval after the effective date of this ordinance shall bear upon its face the report of the Planning and Zoning Commission of the proper names of any and all streets, avenues, and public ways hereafter dedicated to public use within the jurisdiction of the Mayor and Council shall first be checked by the Planning and Zoning Commission as to their names under the provisions of this ordinance.

"SECTION 15. This ordinance and all house and building numbers assigned under the provisions thereof, and all street numbers and names established by said ordinance shall become effective one year from the date the Mayor and Council of said city shall by resolution accept and ratify the recommendations made by the Planning and Zoning Commission for the names of all streets, avenues, and public ways within said City, and shall determine that the superintendent of streets has completed the survey required by Section 7 of this ordinance.

"SECTION 16. The Mayor and Council by resolution may change, rename, or name an existing or newly established street within the limits of said city at any time after the adoption of this ordinance upon recommendation of the Planning and Zoning Commission, and after consultation with the Board of Supervisors, the County Planning Agency, and any other municipality directly affected thereby."

Copyright, American Society of Planning Officials, 1950.