Condominium

PAS Report 159

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 159 | June 1962 |

Condominium

Download original report (pdf)

Prepared by Frank S. So

A significant increase in interest by builders and public officials in the "condominium" has taken place during the past year. Principal impetus has come about with the passage of Section 234 of the 1961 Housing Act (Public Law 87-70, 87th Congress), which provides a new method — at least in this country — of financing cooperative apartment buildings. The result is a system of property ownership that enables an individual to own, mortgage or sell an apartment unit with relatively the same ease as he could with a single-family dwelling.

Because the concept is new in the United States and a number of issues germane to the operations of local planning agencies are raised, this report will attempt to outline some of the basic principles of the condominium. In addition, those aspects of the concept that are related to planning and zoning will be examined. Many legal and financial facets of the condominium are not within the scope of this report. The reader wishing to pursue these topics should consult the bibliography.

A Concept of Property Ownership

Although new in the United States, the condominium is an ancient form of ownership, which was recognized in Roman law. At present, it is a relatively popular form of ownership in Puerto Rico and a number of European nations. It can perhaps be best explained in terms of a comparison with the well-known cooperative apartment. The difference between the condominium and the cooperative is the difference between owning property in fee simple and owning shares in a cooperative organization. However, the condominium is still a form of cooperative ownership.

The "Co-op"

In a cooperative apartment building, an individual owns stock in a corporation with the right through a proprietary lease to occupy an apartment. The corporation, or at times a trust, holds title to land and buildings and has the right to mortgage the property. While the individual apartment dweller is sometimes referred to as a "tenant-owner," he does not actually own his own unit. He is still a tenant under provisions of a lease which is subject to forfeiture under certain circumstances. Because the individual does not have the right to negotiate his own mortgage, there is always the possibility that he may lose his investment through the foreclosure of a blanket mortgage on the structure and land. Because of the nature of a cooperative venture, the rights and responsibilities of the individual stockholder must be clearly spelled out in the proprietary lease. The cooperative apartment dweller must also face the possibility that in the event another tenant does not meet his financial obligations to the cooperative, the cost will then have to be assumed by the rest of the tenants. If only one or two tenants failed in these obligations, the burden would not be too great; however, if a substantial number did so, the burden could be great enough that a foreclosure of the mortgage or a significant decrease in the level of maintenance might result. Thus, there is a degree of risk that an individual could lose his financial interest in the co-op through no fault of his own.

Condominium

Condominium is defined by Webster as "Joint dominion or sovereignty; joint ownership." As applied to the ownership of real estate, "it means ownership in common with others of a parcel of land and certain parts of a building thereon which would normally be used by all the occupants; such as yards, foundations, basements, floors, walls, hallways, stairways, elevators and all other related common elements, together with individual ownership in fee of a particular unit or apartment in such building. It is not confined to ownership of a residential unit such as an apartment, but its use also extends to offices and other types of space in commercial buildings."1

In essence, then, an individual owns a cubicle of air space containing his apartment, and also owns an undivided interest in all the common elements of the building and grounds. Each individual owns a fee title to his apartment which he may sell, mortgage or devise as he could with a single-family dwelling that he owned. An exception to this is that other co-owners have a "right of first refusal." That is, the seller must first offer the apartment to the other co-owners, who then must act on the offer within a specific number of days. The relative advantages of both cooperative and condominium forms are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Comparison of Condominium and Conventional Cooperative

| Condominium | Stock and Lease Cooperative |

| Personally liable on mortgage and for taxes and upkeep. | No personal liability, but may abandon with surrender of equity. |

| Default of one co-owner on mortgage or faxes will not involve others. | Default on any portion of assessment obliges others to make up, to protect their interests. |

| Default of one co-owner on maintenance charges obliges others to make up deficit. | Same; see above. |

| No limitations on right of resale. | Applicants carefully screened by tenant committee; those not satisfactory to majority cannot buy. |

| Standard of maintenance controlled by tenant policies set by majority. | Same. |

| New improvements only when agreed to by unanimous consent. | New improvements when authorized by board of directors; or for large expenditure when ratified by 2/3 of members. |

| Easily refinanced in event of resale with new full mortgage. | Cannot be refinanced independently. If substantial mortgage payments have been made, then seller must provide secondary financing. |

| Purchaser acceptance difficult. Must study many details of individual project to understand it. Documents difficult to simplify without benefit of a state law. | Purchaser acceptance easy. Most buyers understand corporation law and stockholder's rights. Leases are similar to renting leases. |

SOURCE: William S. Everett, "Condominium — New Style Cooperative Apartment," Skyscraper Management, November, 1961, p. 13.

The popularity of the condominium in Puerto Rico has come about partly because of a shortage of in-town land for development. This is particularly serious when a family cannot afford the cost of long commuting. There is apparently a very strong desire for home ownership in the territory; but this desire does not necessarily have to be fulfilled through the ownership of a free-standing single-family house. Consequently, the condominium apartment fills this local need. At the same time, its proponents claim, the condominium may be a method whereby densities can be increased.

It is not clear how popular this form of ownership will be in the United States. Although the desire for home ownership is great, it is doubtful that this quasi-abstract concept is the only reason that the single-family house is popular. The physical structure itself, private yards, and the general kind of neighborhood and community environment in which the typical house is found probably play a far more important role in the choice between an apartment and a single-family house. Some lenders and builders have exuberantly said that the condominium will revolutionize the housing market in such a way that the number of multi-family units will increase considerably. More moderate voices, however, have predicted that the condominium form of ownership will probably replace present cooperatives, induce purchases by some people who presently live in rental apartment units, and only modify very slightly the number that would normally live in a single-family house. The use of the condominium principle may, however, make certain kinds of developments, such as the cluster subdivision, more feasible.

State Legislation

State legislation governing the ownership of property held in condominium has been recommended for a variety of reasons. One of the most important is that the Federal Housing Administration's mortgage insurance program for the condominium under Section 234 of the National Housing Act requires that there be state real property laws to permit the separate taxation of individual apartment units. In addition, real property law in general and legal facets of the condominium are complex enough to warrant some special consideration through specific legislation. Puerto Rico has had a "horizontal property act" since 1902, and is presently operating under legislation adopted in 1958. FHA already has prepared model state legislation on condominium.2 As of April 1962, various kinds of action were being undertaken in the following states:3

In Hawaii, an enabling "horizontal property act" was on Governor Quinn's desk 10 days before President Kennedy signed the 1961 Act last June and the Governor made his state the first to qualify for FHA Section 234 loans 10 days after the signing.

In Arkansas, a bill opening similar doors was offered at a special assembly of the legislature in July. Governor Faubus signed the bill in September and the law went into effect immediately. Speedy action here was to accommodate a prospective Little Rock developer interested in condominium, who later, however, lost out on the job.

In Virginia, condominium legislation passed both houses unamended in March 1962. Earlier, 98 FHA-backed townhouses labeled condominiums had been put under construction in Richmond. However, only the commonly-held recreation areas were financed under Section 234; the houses under Section 220.

In New York, a bill enabling an apartment owner to get a long-term mortgage of up to 30 years, insured by FHA on more than 90 per cent of value, was introduced early in the 1962 legislative session and is to be the focal point of a special study.

In Maryland, a joint resolution has been submitted, recommending a study of the condominium.

South Carolina's lower house has this year passed condominium legislation, with the senate awaiting, as of early March, a committee report on the subject.

In Kentucky, a "horizontal property act" went before the state legislature on February 26.

Arizona had two condominium bills up for 1962 action, both submitted for study to four house committees and with one approved by the senate.

In California, groundbreaking for an 18-story, 161-apartment condominium is expected in San Francisco sometime in May. Already under way is a 22-story building, with individual apartment ownership anticipated at costs ranging from $43,900 to $255,000. In addition, the city's Alexander Hamilton Hotel is expected to be converted into a 195-apartment condominium. While the state does not have a special condominium law, its tax assessment law has been interpreted to apply, though loosely. FHA is awaiting further clarification of the law but a separate "horizontal property act" may have to get through the legislature before FHA will guarantee Section 234 loans.

A comment should be made at this point concerning the use of the words "vertical" and "horizontal." Some references have been made to vertical subdivision when discussing the condominium. Actually, this designation is incorrect. State legislation concerning the condominium form of ownership is sometimes referred to as a "horizontal" property act. This is because the historical concept of land ownership in fee simple is that the owner not only owns the surface of the land, but an infinite distance above the surface and to the center of the earth below the surface. The condominium is, then, a process by which horizontal layers above and below the surface can be subdivided and sold. At times, confusion could be avoided if the term "aerial subdivision" were used instead.

Characteristics

The model legislation prepared by FHA provides a very useful framework for discussion of many of the characteristics of the condominium.

An apartment is defined as a part of the property intended for independent use with access to a public street, either directly or through a common area. This definition presumably can also include privately owned areas such as garage spaces and storage areas. "Apartment" is not necessarily limited to mean only residential property; it can also mean an office in a commercial building. A condominium building must contain at least five or more apartments; or it may be two or more buildings, each containing two or more apartments, with a total of at least five apartments. Each apartment, together with its undivided interest in the common areas and facilities, for all purposes constitutes real property, and each apartment owner has exclusive ownership and possession of his apartment.

The common areas and facilities usually include:

1. The land on which the building is located.

2. The foundations, columns, girders, beams, supports, main walls, roofs, halls, corridors, lobbies, stairs, stairways, fire escapes, and entrances and exits of the building.

3. The basements, yards, gardens, parking areas and storage spaces.

4. The premises for the lodging of janitors or persons in charge of the property.

5. Installations of central services such as power, light, gas, hot and cold water, heating, refrigeration, air conditioning and incinerating.

6. The elevators, tanks, pumps, motors, fans, compressors, ducts and in general all apparatus and installations existing for common use.

7. Such community and commercial facilities as may be provided for in the declaration.

8. All other parts of the property necessary or convenient to its existence, maintenance and safety, or normally in common use.

In the model act, both a "declaration" and a floor plan must be filed with the appropriate recording officer. The declaration is the legal instrument by which the property is submitted to the provisions of the state act. It contains, among other things, descriptions of the land, buildings and other improvements; a description of each apartment to include its location, area, number of rooms, areas to which it has common access, and any other information needed to properly identify the apartment; description of the common areas and facilities; value of the property and of each apartment; and provision as to the percentage of votes by the apartment owners needed to determine whether to rebuild, repair or sell the property in the event of damage or destruction of all or part of the property.

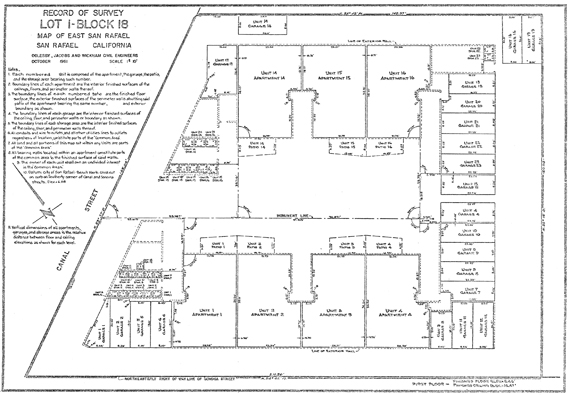

A copy of the floor plans of the building must also be submitted, along with the recording of the declaration in the recorder's office. The plans must be prepared by a registered architect or registered professional engineer and must show the layout of each apartment with both horizontal and vertical dimensions. Although not mentioned in the model legislation, it has been recommended that specific monuments be placed at various points in the building to make measurements more accurate. Measurements are usually made along the surface of the unfinished walls. In addition, because every structure settles to a certain extent because of natural conditions, the deed to each apartment contains provisions concerning easements to allow for encroachments that will take place as the building settles. The recording officer keeps a separate file for each condominium building.

Reproductions of portions of floor plans for two condominium projects in California appear in the appendices, and they deserve close study because they illustrate many of the characteristics of the condominium type of property.

In addition to the provision that each apartment shall constitute real property, the most important provision from the viewpoint of FHA is that each apartment shall be separately taxed. The pertinent section reads:

Each apartment and its percentage of undivided interest in the common areas and facilities shall be deemed to be a parcel and shall be subject to separate assessment and taxation by each assessing unit and special district for all types of taxes authorized by law, including but not limited to special ad valorem levies and special assessments. Neither the building, the property nor any of the common areas and facilities shall be deemed to be a parcel.

The model act also provides for the creation of an association of apartment owners, which may elect a board of directors, and officers. The duties of the association, or the board acting for the association, are quite important. It, perhaps through a manager, must establish bylaws, keep accurate financial records concerning the common areas and facilities, take care of maintenance, repair and replacement of the facilities, determine assessments for maintenance, establish rules and regulations concerning use of the facilities, and determine requirements and restrictions respecting the use and maintenance of the apartments. The standard of maintenance and the numerous aspects of necessary normal maintenance are subject to majority rule of the association. However, any substantial and new improvement must be approved by unanimous consent.

Perhaps one of the most important functions of the association is the decision it must make in the event of a partial or total destruction of the property. The individual condominium deed usually contains detailed agreements concerning such an event. Provision is made that the building must be adequately insured and that in the event of destruction, the disposition of the proceeds, whether used to rebuild or distributed pro rata, will be determined by a specified majority of the apartment owners. Since the concept of condominium ownership is new in the United States, there is some disagreement among legal experts whether this solves the problems created by destruction. One solution is to have the owner possess a fee in the cubicle air space enclosed by the apartment, which would survive any destruction of the building. When the building was reconstructed, title to the tangible portions of the building would again belong to the owner of the air space. To prevent the problems which could come about because of the survival of title to air space, others have suggested that the apartment be conveyed as a fee simple determinable rather than a fee simple absolute. By this means, if no decision were made to reconstruct a destroyed building after a given time period, a reverter clause would vest title to all air spaces in the owners as tenants in common.

Subdivision Regulations and Zoning

With start of a number of condominium projects, questions have been raised about how zoning and subdivision ordinances apply to this sort of development. Among the questions that have been asked are the following:

Should a condominium be treated any differently than a conventional project only because of the ownership pattern?

If it should be treated differently, then how can zoning provisions concerning minimum lot and floor area, maximum building coverage, required yards, and off-street parking requirements be handled?

Must definitions of "lot," "parcel" and "subdivision" be modified? What of requirements that lots or parcels must front on a public street?

Can condominium projects be processed best under planned unit development provisions?

If the condominium is processed by the planning agency as a subdivision, what standards should guide the planning agency in either accepting or rejecting a specific proposal?

Unfortunately, there is very little experience with the condominium on which to base any generalizations. In addition, much of the interest, or perhaps more accurately the response by public officials, has been shown in California. Consequently, planning agencies in other states may yet have the problem of resolving the problems that by this time are being resolved in California.

Subdivision Regulations

The California Attorney General ruled that a condominium development of 24 units similar to town or row houses was subject to the state's Subdivision Map Act and was not within the record of survey exception to that act.4 The act provides that a subdivision does not include a division of property when all of the following conditions are present: the whole parcel contains less than five acres; each created parcel abuts a public street; no street openings or other public improvements are required; and the lot design meets local requirements.

Based upon previous opinions and court decisions, the reasoning of the Attorney General goes somewhat as follows: The words "lot" and "parcel" do not necessarily refer to physical pieces of land and may include interests in real property. In addition, the conveyance of five or more undivided interests in real property together with the right of exclusive occupancy of a unit is a subdivision within the provisions of the act. Since the conveyance of a fee includes exclusive occupancy, the division of real property into parcels of air space to be owned in fee is a subdivision subject to the provisions of the act. The requirement that divided parcels must abut a public street to be excepted from the provisions of the act is not met in a condominium with parcels of air space since the parcels may not "touch" or "reach" the street. Finally, the words "lot" and "parcel of land" refer to real property, and not necessarily land.

In accordance with the Attorney General's opinion, the Santa Clara County, California, Planning Department has worked out the following procedures regarding condominium projects:5

a. All condominium projects will be filed as a subdivision in accordance with the County's subdivision ordinance:

1. Tentative maps to be filed with the same information as required on any other subdivision.

2. The maps will be reviewed in the same manner, and presented to the Planning Commission in the same manner as any other subdivision.

3. Condominium subdivisions of five or more "parcels" (units) of real estate will be required to file a final map with the same certificates and requirements as any other 5-lot subdivision.

4. Condominium subdivision of four lots or less will be required to file a Record of Survey and submit any other instruments deemed necessary by Public Works and County Counsel.

b. All condominium projects, whether apartments, commercial, or industrial buildings, that require architectural control will be reviewed very closely to insure the highest quality of development possible. Most all zones providing for multi-family, commercials, industrial development do require architectural control.

c. Allowance should be made for more than the normal time required for processing any condominium development as the first developments come in. Once a few developments are processed through, there should be no difference in processing time than any other type of development.

It should be noted that the above statement is not a local ordinance, but rather a policy statement outlining the department's intent in processing such developments.

The point of view that the condominium should not be subjected to normal kinds of subdivision review has been expressed a number of times.6 The basic view is that "cities should view such developments just as they would a conventional apartment house project and not impose additional regulations or requirements on the condominium project simply because occupants of the individual units will be owners instead of lessees or tenants."7

Since planning commissions often require the provision or dedication of certain improvements as a condition for subdivision map approval, there is concern that they could require improvements of a condominium project which would not be required of a similar rental property. In addition, most subdivision regulations are drafted with large open land in mind that will require streets, sewers and similar kinds of improvements. Since many condominiums will be located on previously platted in-city sites, these kinds of improvements will seldom be needed. If specific improvements are needed, they can be provided in some circumstances by the assessment of benefited property owners. There would also be the problem of what design standards should be applied. In the light of state and local building and housing codes which set minimum room sizes, additional requirements administered by a planning body would be superfluous.

The procedural requirement that both preliminary and final maps be submitted for planning commission review, as required in most states, has also been criticized. The feeling is that a single map, submitted once and then recorded with the proper recording officer, is adequate to protect the prospective purchaser and to properly identify each individual unit. Because many planning commissions require the submission of a significant amount of supporting data in addition to maps, it is felt that the expense of an additional map is unnecessary.

Draft legislation in California proposes that Section 11535 of the California Subdivision Map Act (Business and Professions Code Sections 11500 et seq.) be amended to read as follows:8

(f) Condominium subdivision and community project.

"Subdivision" does not include a condominium project as defined in Civil Code Section 687.1 or community apartment project as defined in Section 11004 of this Code. In either such case, a record of survey map of the surface of the land on which such condominium project or community apartment project is constructed shall be prepared pursuant to the provisions of Chapter 15 (commencing with Section 8700), Division 3 of this Code, together with diagrammatic floor plans of such condominium subdivision or community apartment project, and shall be submitted to the governing body in the same manner as is provided in this chapter for tentative maps and upon approval of such governing body shall be filed in the office of the recorder of the county in which such land is located, and thereupon conveyances may be made of parcels shown on such map and plans by lot or block number, parcel or unit number, or such other designation as may be shown on such map and plans.

A local attempt at solving some of the objections raised in the above proposal was provided in Stockton, California, through the amendment of the subdivision regulations. Impetus for the amendment came about when a development of nine buildings, containing 72 dwelling units on a 2-acre site, was proposed. It was originally planned as a rental project and was processed under special permit provisions for planned unit developments of the zoning ordinance. After a use permit was issued, the developer chose to convert the proposed apartments to a condominium development. The planning commission was obliged to follow the opinion of the state Attorney General and process the project as a subdivision. Since the planning commission felt that the effect of a condominium would be no different than the apartments originally approved, it approved the following amendment to the subdivision regulations:9

Sec. 16-003.4. Unit for Condominium Subdivision:

Unit or condominium subdivision of real property is included within the meaning of subdivision as defined herein and must comply with the subdivision regulations except Sections 16-009 through 16-009.3 and Sections 16-010 through 16-010.6 [requirements for block and lot design]. Such compliance shall include, but not be limited to the filing of tentative and final maps, the dedication and improvement of rights-of-way, roads and streets, and the payment of fees, charges and contributions. The conveyance of land for neighborhood facilities or park and recreation areas shall not be required, but in lieu thereof a contribution shall be required in an amount established by resolution of the City Council. The reservation of land for parks, playgrounds, school sites, or other public uses on a regional basis shall not be required.

Tentative and final maps shall indicate and clearly define each unit or parcel and shall indicate public easements, common areas, and improvements, all easements appurtenant to each unit, improvements to public rights-of-way and provisions for parking of owner and guest vehicles.

Unit or condominium subdivisions are subject to zoning regulations as they apply to use districts and density requirements. Setbacks, parking, and other features shall be clearly indicated on the subdivision map.

Even if the planning authority "eases up" on its procedural requirements for processing a condominium project as a subdivision map, most developers would still prefer filing a record of survey map since there are far fewer other governmental agencies that must then approve the proposal.

Zoning

The application of local zoning ordinances to the condominium development has created a number of problems, but by no means do they appear serious or insurmountable. Principal problems revolve around the definitions of "land," "lot" and "parcel" and the regulations, such as minimum lot area, density provisions and yard requirements, that are based upon a given unit of property, such as the lot. To a great extent, the problems have come about because of the lot-by-lot approach of the typical zoning ordinance.

Many planning commissions will be faced with the problem of what to do when a multi-family building to be sold on a condominium basis is submitted for approval. Does the minimum lot area for multi-family structures apply to each individual dwelling unit? Is the individual apartment a parcel of real property? If a rowhouse development is proposed, and the "lot" lines follow the outside front and back surface of the structure, what becomes of the minimum requirements for rear and front yards?

It is unrealistic to treat a development differently purely because of the ownership pattern alone. The impact on the surrounding area and the demand for public services would be the same whether an apartment building is a rental unit, cooperative or condominium. This principle is expressed in proposed state legislation in California:10

Unless a contrary intent is clearly expressed, local zoning ordinances shall be construed to treat like structures, lots or parcels in like manner regardless of whether the ownership thereof is divided by the sale of condominiums rather than by lease of apartments.

When a zoning ordinance defines "lot" as a parcel of "land," which includes occupied air space as indefinite distance upwards, confusion results if it is therefore concluded that a condominium unit is a lot and thus subject to minimum lot and yard requirements. Redefinition of these basic terms is needed. One effort in this direction is a proposal to redefine "land" in the California Civil Code.11 Other solutions are also possible.

Recognition of rights in air space, with the provisions that like structures and lots be treated alike in zoning ordinances, can clear up some of the confusion that may come about, as well as being more equitable. In addition, it may be desirable to define an air space in a condominium multi-family differently than a "lot." For example, in a condominium project in San Jose, the city's minimum lot size of 5,000 square feet was overcome by defining air spaces as "units" rather than as "lots." In some cases, it may be possible to interpret the existing ordinance in such a manner that a condominium apartment is treated like any other apartment structure. Thus, in San Francisco, the Department of City Planning's Zoning Bulletin 62-1 declared:12

The City Planning Code has no provisions that would prevent the separate sale of individual units in a multiple dwelling (apartment building) on a condominium basis.

The Planning Code does contain minimum lot size provisions that might prohibit the separate sale of individual portions of an apartment building site, and it has additional provisions such as those relating to minimum lot area per dwelling unit, maximum ratio of floor area to lot area maximum building coverage, required yards, and off-street parking that might also prohibit separate sale of portions of the site, but none of these questions is raised where the site remains in undivided common ownership.

If the building for which a permit is sought can be approved under the Planning Code on the basis of the building plans and the area of land being committed to the project, the Department of City Planning will approve it on that basis without regard to the nature of the various ownerships there may be in the building and/or land.

Reference should be made here to the definition of "lot" in Section 102.19 of the Planning Code:

"A parcel of land considered as a unit occupied or to be occupied by a main building or groups of main buildings and accessory buildings, or by a principal use and uses accessory thereto, together with such yards, open spaces, lot width and lot area as are required by this Code."

This provision does not refer to ownership interests in any way, though for administrative purposes the Department ordinarily reviews proposals for the use of land in terms of Assessor's lots, which are the basis on which property owners and builders customarily draw up such proposals.

The phrase "none of these questions is raised where the site remains in undivided common ownership" is particularly important because it differentiates, in terms of practical application, an apartment building from a row house or single-family development where the land as well as the dwelling units may be individually owned. As yet, the latter kind of development has not come up for study in San Francisco, but public officials feel that planned unit development provisions may provide a way in which this kind of development can be done.13

The difficulty in establishing land development policies for condominium developments other than apartments was well stated by the Attorney General of California: 14

In general, it should be noted that no uniform rule can be established regarding the applicability of particular regulatory statutes or ordinances to condominium developments through the mere use of such terms as "lot" or "parcel." For example, a local ordinance establishing a "minimum lot size" of 5,000 square feet in a certain area would not appear to be applicable to units in an apartment house, regardless of the nature of the ownership of such units. However, if the units of air space were laid out in single dwellings over a large area, such as is found in some horizontal condominiums, the requirements of "minimum lot size" might well be applicable. It is apparent that each project must be measured against the purposes of the statute in question and the intention of the legislative body in enacting it on a case-by-case basis.

It is entirely possible that the legislative body of a city may still wish to set a minimum lot size for an individual condominium unit within a row or cluster development even if it fully sympathizes with the condominium principle. In essence then, it would say that most of the land in a particular kind of project can be held in undivided ownership, but that a specific amount of land surrounding each separate unit should be owned in fee. For example, Palm Springs, California, requires that each single-family condominium unit shall contain a minimum of 4,500 square feet of lot area. Similarly, condominium projects constructed in Berkeley, California, and Richmond, Virginia, have met the requirements of the zoning ordinance for gross density, building coverage, open space and off-street parking.

The planned unit development provision in the zoning ordinance provides, perhaps, the best means of guiding the development of a condominium project. Because the concept has been adequately discussed elsewhere,15 it will not be covered here at length. However, a number of planners who have given some thought to the condominium type of development have concluded that planned development provisions provide the greatest degree of flexibility, while maintaining adequate controls over land development. It is thus possible to vary the requirements for minimum lot size, maximum building coverage, minimum front, side and rear yards, and distance between structures, while at the same time providing more open space and community facilities, lowering developmental costs, and allowing greater design freedom.

A word of caution concerning the community's land development ordinances and their application, or misapplication, to the condominium is in order. Planning agencies will always have to cope with the land developer who purposely subverts a valid development concept in order to make a quick dollar. If the concept is relatively new, the developer has the ignorance of the public official working in his favor. Paradoxically, the developer describes his proposal with virtuous adjectives of "progress" and "flexibility." Introduction of the planned unit development has provided many examples of how developers have interpreted flexible provisions, designed to lessen the bad results of admittedly rigid zoning and subdivision requirements, as a signal to move backwards to the days before any community regulations were in force. The use of the condominium has already provided us with the example of this type of developer.

A planning commission has recently confronted with a proposal of a developer based upon the condominium concept. The site of the proposal was slightly larger than ten acres and was located in a zoning district requiring a minimum lot area of 7,000 square feet per dwelling unit. The proposed development consisted of almost 150 detached single-family houses. The resulting density would be just under 15 dwelling units per gross acre — more than double the density prescribed in the zoning district. There would be no lot lines as such; each house would be individually owned, with accompanying driveways being privately maintained. All of the land, including streets, would be held in condominium. Taxes and payments for services such as water and sewers were proposed to be prorated to the individual owners.

The site plan provided an arrangement of houses much like any typical detached single-family subdivision. Each dwelling was set back from the street an identical distance, with relatively the same amount of space for side and rear yards. In essence, each unit was placed in the middle of a site as if there were rigid lot lines and yard requirements that had to be observed. Average distances between sides of houses were ten feet; rear yards averaged fifteen feet in depth, with some even smaller. This pattern was then duplicated throughout the entire development. No open space or any kind of community facility was provided. The street system was essentially a modified gridiron with curves appearing at right angle tangents. The right-of-way for all streets was thirty feet.

This proposal was an obvious attempt to circumvent the community's land development ordinances. Used properly, the condominium, in conjunction with planned development provisions, can be used as a technique to accomplish design solutions that have not been executed very often in the past because of rigid zoning and subdivision ordinances. Examples are the cluster subdivision and hillside development containing common recreation areas.

Conclusion

The condominium form of property ownership will probably grow in popularity, because of a number of advantages over other forms of tenure, such as the stock cooperative, and because of the federal government's mortgage insurance program. This type of ownership will largely be used in multi-family apartment structures, but it may be used to some extent in single-family dwellings. In the latter instance, the concept may foster more variety and design flexibility in residential neighborhoods.

Although there are complexities in the legal and financial aspects of the condominium, these do not necessarily cause problems for the planner since their solution lies outside the area of his professional competence. The problems that primarily concern the planner — zoning and subdivision regulation — seem relatively easy to solve through the modification of state and local legislation. Such things as minor changes in definitions and procedures come to mind.

Perhaps most important of all, the difficulty in applying land development ordinances to the condominium demonstrates some of the basic faults of the traditional, lot-by-lot, rigid techniques of zoning and subdivision land development control. Localities which have not kept their land development ordinances up to date by the addition of such provisions as the planned unit development provision will find it difficult to process condominium projects. But those agencies which have continually re-evaluated their regulations and controls will take the condominium and the challenges it presents in stride.

References

1. Charles E. Ramsey, "Condominiums: The New Look in Co-ops, " Urban Land, Vol. 21, No.5, May 1962, p. 3.

2. Federal Housing Administration, "Condominium: Model Statute for Creation of Apartment Ownership and Commentary," Notice No. F-428, May 10, 1962.

3. "States Get Going on Condominium Legislation," Journal of Housing, March–April, 1962, p. 137.

4. 39 Ops. Cal. Atty. Gen. 82, Opinion No. 61-299, February 9, 1962.

5. Policy Statement of the Santa Clara County, California Planning Department, May 15, 1962.

6. See, for example, Robert P. Berkman, "Condominium — A New Concept." Paper presented to the League of California Cities, Spring Conference, 1962; and, Herbert J. Friedman and James K. Herbert, "Community Apartments: Condominium or Stock Cooperative?" California Law Review, Vol. 50, No, 2, May 1962, esp. pp. 336–38.

7. Berkman, op cit., p. 10.

8. Ibid., p. 7.

9. Letter from Herbert L. Epstein, Assistant Director of Planning, Stockton, California Planning Department, September 17, 1962.

10. Berkman, op. cit., p. 9.

11. Ibid., p. 8.

12. "Application of City Planning Code to Condominiums," Zoning Bulletin 62-1, San Francisco Department of City Planning, July 30, 1962.

13. Letter from Clyde O. Fisher, Jr., Zoning Administrator, San Francisco City Planning Department, September 12, 1962.

14. 39 Ops. Cal. Atty. Gen., at 85.

15. See, for example, New Approaches to Residential Land Development: A Study of Concepts and Innovations, Technical Bulletin No. 40, Urban Land Institute, January, 1961; and, Density Zoning: Organic Zoning for Planned Residential Developments, Technical Bulletin No. 42, Urban Land Institute, July, 1961.

Acknowledgements

The ASPO Planning Advisory Service wishes to thank the following individuals for their assistance in the preparation of this report:

Janice B. Babb, Director, Department of Information, National Association of Real Estate Boards, Chicago; James A. Barnes, Director of Planning and Assistant City Manager, Berkeley, California; Richard Coleman, Planning Director, Palm Springs (California) City Planning Commission; Herbert L. Epstein, Assistant Director of Planning, Stockton, California; Clyde O. Fisher, Jr., Zoning Administrator, San Francisco Department of City Planning; Hal J. Giblin, Senior Planner, San Jose (California) Department of City Planning; Robert L. Sturdivant, Associate Planner, Santa Clara County (California) Planning Commission; and A. Howe Todd, Director, Richmond (Virginia) City Planning Commission.

Bibliography

Anderson, Seneca B. "Cooperatives and Condominiums," Residential Appraiser, August, 1962, pp. 1–6.

Berkman, Robert P. "Condominium A New Concept." Paper presented to the League of California Cities, Spring Conference, 1962.

Borgwardt, John P. "The Condominium," Journal of the State Bar of California, Vol. 36, No. 5 (September–October, 1961), pp. 603–612.

Condominium. Summary Proceedings on the briefing presented to the Santa Clara Planning Commission. San Jose, California: Santa Clara Planning Department, April 18, 1962.

Condominium Abecedarium. Berkeley, California: Associated Home Builders of the Greater Eastbay, Inc., 1961.

"Condominium — First in Midwest," Real Estate News, Vol. 41, No. 3 (July 16, 1962), pp. 5–6.

"Condominium Housing," Urban Land, Vol. 20, No. 5 (May, 1961), pp. 9–10.

Condominium: Model Statute for Creation of Apartment Ownership and Commentary, Washington, D. C.: Federal Housing Administration, May 10, 1962.

Davila, Horrace E. "Condominium: How It Works in Puerto Rico," Savings and Loan News, April, 1961, pp. 42–45.

Ellman, Howard N. "Condominium: Present Financing Market in California and How to Reach It," California Builder, July, 1962.

Everett, William S. "Condominium and Cooperative Apartments," Journal of Property Management, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Fall, 1961), pp. 4–16.

———. "Condominium — New Style Cooperative Apartment," Skyscraper Management, November, 1961, p. 12 ff.

"FHA Mortgage Insurance on Condominiums," FHA Fact Sheet No. 491. Washington, D. C.: Federal Housing Administration, May, 1962 (revised).

Friedman, Herbert J., and Herbert, James K. "Community Apartments: Condominium or Stock Cooperative?" California Law Review, Vol. 50, No. 2 (May, 1962), pp. 299–341.

Ho, Chinn. "Cooperative Apartments and Condominium," Appraisal Journal, October, 1961, pp. 529–531.

Murray, Robert W., Jr. "Condominium," House and Home, December, 1961, pp. 148–149.

Neville, James F. "Condominium Gaining Favor in U.S.," 11 Journal of Home Building, October, 1961, pp. 65–69.

Ramsey, Charles E. "Condominiums: The New Look in Co-ops," Urban Land, Vol. 21, No. 5 (May, 1962), pp. 1–3.

"States Get Going on Condominium Legislation," Journal of Housing, March–April, 1962, p. 137.

U.S. Senate, Committee on Banking and Currency. Housing Legislation of 1960, pp. 585–608. 86th Congress, Second Session, May, 1960.

Vogel, Harold N. "A New Break for Apartment Owners," Architectural Forum, September, 1961, pp. 132–133.

Appendix A

(Reproduced from Condominium Abecedarium, courtesy of Associated Home Builders of the Greater Eastbay, Inc., Berkeley, California.)

Appendix B

(Reproduced from Condominium Abecedarium, courtesy of Associated Home Builders of the Greater Eastbay, Inc., Berkeley, California.)

Copyright, American Society of Planning Officials, 1962.