Planning February 2020

Cities That Love the Nightlife

A thriving nighttime economy is critical for fostering a vibrant city.

By Jeffrey Spivak

When the Iowa Chapter of APA held its annual conference in Iowa City this past fall, the members had a special escort for their nights out in the downtown: the "Nighttime Mayor."

That is Joe Reilly's actual job title. It says so right on the lapel pin he wears when he's out on the town at night as an ambassador and troubleshooter in the Iowa college town. He took the Iowa Chapter planners on a progressive dinner during one night of their conference. Another night, he guided them on a pub crawl. On the last day, he led a walk to view the downtown murals.

"I hadn't really heard of a nighttime mayor before, but he made us feel more like insiders going to the cool spots in town," says Madeline Sturms, AICP, the conference cochair and the community development director for Pleasant Hill.

Being the Nighttime Mayor sounds like a fun job, and for the most part, Reilly says, it is. "I can have a beer on the job," he adds.

Iowa City's nighttime mayor Joe Reilly has fun on the job — which sometimes involves costume parties and pub crawls. He helps find commonsense solutions to tackle concerns of business owners during homecoming and other busy times. Photo courtesy Joe Reilly.

But this type of job is also very serious business across the country. Nationwide, about a dozen cities, large and small, have created a nighttime ambassador-advocate role in the last several years, following in the footsteps of several European cities, including London, Paris, and Zurich. The U.S. roles don't all have the same title — there's the nighttime economy manager in Pittsburgh and Fort Lauderdale; the nightlife business advocate in Seattle; the 24-hour economy ambassador in Detroit; the director of the mayor's nightlife office in New York City and Washington D.C.; and so on.

But they all are commonly referred to as "night mayors," and they tackle issues common to entertainment or bar districts, their nearby neighborhoods, and night-shift workers. Issues like permitting challenges for new businesses, wee-hours transportation options, noise and trash complaints, even the need for specialized planning and development guidance.

"People ask, 'What's an office of nightlife? What's it do, throw parties?'" says Andrew Rigie, chair of New York's Nightlife Advisory Board and executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, an advocacy group for some 24,000 nightlife establishments and hotels in that city. "No, we're really addressing some very serious issues. We can play a key role in fostering an environment that allows a vibrant nightlife to grow."

The main drag of Pittsburgh's South Side — East Carson Street — is home to some 40 bars, including the historic Double Wide Grill. Allison Harnden, Pittsburgh's nighttime economy manager, helped rally city officials and government departments behind a strategy to raise funds for safety and sanitation enhancements. Photo by Russell Kord/Alamy.

Could Your City Use a Night Mayor?

Cities small and large are still defining the role of night mayor, and have a variety of approaches. In general, the nighttime-nightlife jobs take on a variety of roles:

OMBUDSMAN and point of contact for businesses to help them work through government permitting and regulatory processes, although nighttime managers don't have any enforcement authority

FACILITATOR and mediator between residents, businesses, and city government when there are complaints

REVIEWER of new developments or special permits, to offer guidance about avoiding possible problems

PROMOTER of downtown or entertainment district activities and culture, while balancing the interests and needs of surrounding neighborhoods

ADVOCATE for overlooked night-shift workers to, among other things, create safer environments and provide more transportation options

The rise of 'night mayors'

That helps explain why these night mayor-type positions are emerging now. More cities are trying to develop vibrant nightlife to become more attractive places to live and work. Downtowns have increasingly become mixed-use environments, existing as office and retail centers by day and turning into residential and cultural centers at night. But this has created some challenges that didn't exist a decade or so ago. Such as downtown residential developments next to music venues. Or rising rents pushing out popular, long-established watering holes. Or ride-hailing services causing traffic jams after events.

The nighttime ambassador-advocate role is one new way cities are promoting nightlife growth while also helping to ease some of the growing pains. In a lot of cases, it involves or requires planning.

Take San Francisco, for instance. It was one of the pioneers of the nighttime role, with a position created in 2013, so it's been on the leading edge of using the position as a planning liaison. One issue involved new residential developments occurring in entertainment corridors. Ben Van Houten, the city's business development manager for nightlife, coordinated a process involving city government agencies and elected supervisors that led to the city adding an extra planning review for developments proposed close to music venues. This review offers sound-mitigation suggestions for the developers, such as thicker exterior walls and placing bedrooms as far away as possible from the music venue.

"We've been able to avoid conflicts by some early intervention," Van Houten says. "Planning for the nighttime economy is critical for fostering a vibrant city."

A "rogue band" makes appearances at Iowa City watering holes for Friday night home games. Photo courtesy Joe Reilly.

What 'night mayors' do

When night mayors talk about "nightlife," they don't just mean bars and nightclubs. Nightlife also encompasses restaurants, theaters, concert halls; a number of businesses and institutions that remain open at night, like hotels, gas stations, and hospitals; and night-shift workers and those on the roads, such as Uber and delivery drivers.

While all this activity has traditionally been concentrated in downtowns, it's increasingly spreading to additional areas or districts in many cities. "We're seeing an evolution and a recognition that the nighttime economy is an economic driver throughout a city," says David Downey, president of the International Downtown Association in Washington, D.C., and a former executive director of APA's Michigan Chapter.

It all adds up to some significant economic impacts. A study for the New York City mayor's office in 2019 found nighttime industries supported almost 300,000 jobs and contributed $35 billion in economic output across that city. A 2016 study in San Francisco pegged nighttime employment there at 60,000 in more than 3,500 businesses. Overall, the Washington, D.C.-based American Nightlife Association states the U.S. bar and nightclub sectors alone account for $783 billion in revenue and economic activity, and U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey data has shown that 17 percent of workers in major metropolitan areas report to jobs between 4 p.m. and 6 a.m.

Resonance Consultancy, a firm in Vancouver, B.C., publishes annual rankings of "America's Best Cities" based on some two-dozen factors. It has found that a city's ranking is strongly correlated with the quality of its nightlife.

"Nightlife is one of those things we think of as being nice to have, but it's increasingly more of a 'need to have' quality in order to attract talent, tourists, and capital to a city," says Chris Fair, Resonance's president.

The emergence of night mayors is one small piece of cities' growing acknowledgment and appreciation of that fact. The actual role of the nighttime ambassador-advocate is still evolving. So far, there's been no single or common approach to its structure. Some jobs are part of a city government office; others are part of a downtown-related agency. Some are part of a nightlife team; others are one-person shops. Some work a combination of daytime and nighttime hours; others are more focused on regulatory or government relationships, resulting in traditional nine-to-five hours.

In a nutshell, these tasks typically involve different forms of relationship-building and collaboration. "There's a lot of liaisoning that's invisible but really important work, just to have someone think about and work on issues," says Ray Gastil, AICP, a former Pittsburgh planning director who has worked with that city's nighttime economy manager and now is director of the Remaking Cities Institute at Pittsburgh's Carnegie Mellon University.

Juan Carlos Diaz, a consultant and president of the American Nightlife Association, summarizes the nighttime role this way: "It's not a threat to the daytime mayor; it's more of a support system, someone who understands and is dedicated to the issues that occur at night."

That understanding and dedication can, in some cases, lead to pretty common-sense outcomes and solutions. In Iowa City, after years of complaints from downtown businesses that homecoming weekend crowds would relieve themselves in back alleys and even planter beds, the nighttime mayor arranged to supply outdoor portable toilets. In New York City, after years of complaints from residents about trash and odors left behind by nightclub-goers, the nightlife office worked with city departments to schedule early-morning trash pickups and street cleanings — before the residents wake up.

One lesson learned so far from some experiences in European cities is to have nighttime ambassadors-advocates who are autonomous, independent, and not tied to any political affiliation. In London, for instance, the city's "night czar" has come under fire for her alignment with one political party, leading to concerns about possible favoritism toward certain business owners or areas of the city.

"The voice for nightlife should not be limited to party politics," says Alan Miller, cofounder of London's Night Time Industries Association, a business advocacy group. "You want a diplomat, someone seen as robust and strong, not someone seen as a 'yes' person."

Tips for Managing Nightlife

1. Conduct a Nighttime Assessment

Taking an inventory of existing social, dining and entertainment options; occupancy totals; and infrastructure needs (sidewalk capacity, traffic control, trash, utilities, parking, public facilities, sound management, etc.) will help you strategically allocate resources and determine how many permits and licenses to issue. An economic and fiscal impact study can document revenue, taxes, fees generated, and employment within the hospitality zone.

2. Identify Gaps and Resources

Assess how your community currently meets the social needs of each generation by identifying strengths, gaps, and resources in the following areas — entertainment, public space, quality of life (sound, trash), nighttime mobility (designated transport hubs), venue safety, and public safety.

3. Measure Risk

Monitor crime, harm, disorder, and venue compliance to establish emerging trends and requirements for strategic intervention to reduce risk to safety and quality of life.

4. Dedicate Staff

Select a neutral individual as a nightlife coordinator who will oversee planning and management of your social districts. This person will serve as a liaison among key stakeholders serving on a commission or task force to communicate key information, resolve conflicts, and facilitate implementation of next steps.

Source: Responsible Hospitality Institute, rhiweb.org

Innovative nighttime planning

Nightlife and the nighttime economy are seldom contained in one or two sections of a city. They often grow organically, sometimes expanding into residential neighborhoods or swelling blocks beyond main thoroughfares. This can lead to a need for planning, such as policy or zoning adjustments, to adapt to and manage the new blend of land uses.

"Some of the most innovative solutions in nighttime management came out of proactive planning," says Jim Peters, president of the California-based Responsible Hospitality Institute, which consults with cities on nightlife strategies and hosts annual summits on nighttime economy management.

Consider Pittsburgh. For decades, its South Side neighborhood along the Monongahela River across from downtown was mainly known for its steel plants. But after many of them closed in the 1980s, South Side began a slow transformation into a popular bar district. Today, South Side's main drag — East Carson Street — is home to some 40 bars, from the divey to the upscale, and dozens of others are scattered elsewhere across the neighborhood.

But with South Side's growing popularity came some growing safety and nuisance issues. Overflowing trash cans. Vomiting on sidewalks. Car break-ins and thefts. Even shootings and violent crimes. So in 2016, Allison Harnden, Pittsburgh's nighttime economy manager, helped rally various city officials and government departments behind a strategy to raise new funding for some safety and sanitation enhancements.

The city council ended up creating a special parking district where on-street parking meters would be newly enforced on weekend nights. The $200,000 annual funding is used for extra cleaning crews and to install and monitor security cameras along East Carson Street. It went into effect in 2017; within a year, reported crime dropped 30 percent.

"I feel like I am helping the city of Pittsburgh accommodate and adapt to being if not a 24-7 city then an 18-hour one," Harnden says. In some cities, proactive planning has also been used in the nightlife advocacy side of the nighttime management role. Iowa City's nighttime mayor routinely helps visiting groups plan their nights out downtown. In Seattle, nightlife business advocate Scott Plusquellec has taken that responsibility one step further by involving hotel concierges.

Last fall, Plusquellec organized a bar-hopping tour of the Capitol Hill district for more than a dozen concierges. Over the course of three hours, they bounced from a music venue to a drag-queen bar to a dance club to a jazz joint, and more. It was intended to be a diverse collection of places, so the concierges could get a feel for the vibe at each one — and get a better idea where to suggest a night out for hotel guests, based on guests' individual interests.

"I'm trying to expand the concept of nightlife beyond just white people going to dance clubs so the hotels can send guests out on a more individualized and authentic experience in the city," Plusquellec says. "It's really about seeing nightlife as an asset that makes the city a better place to visit, and live, for everyone."

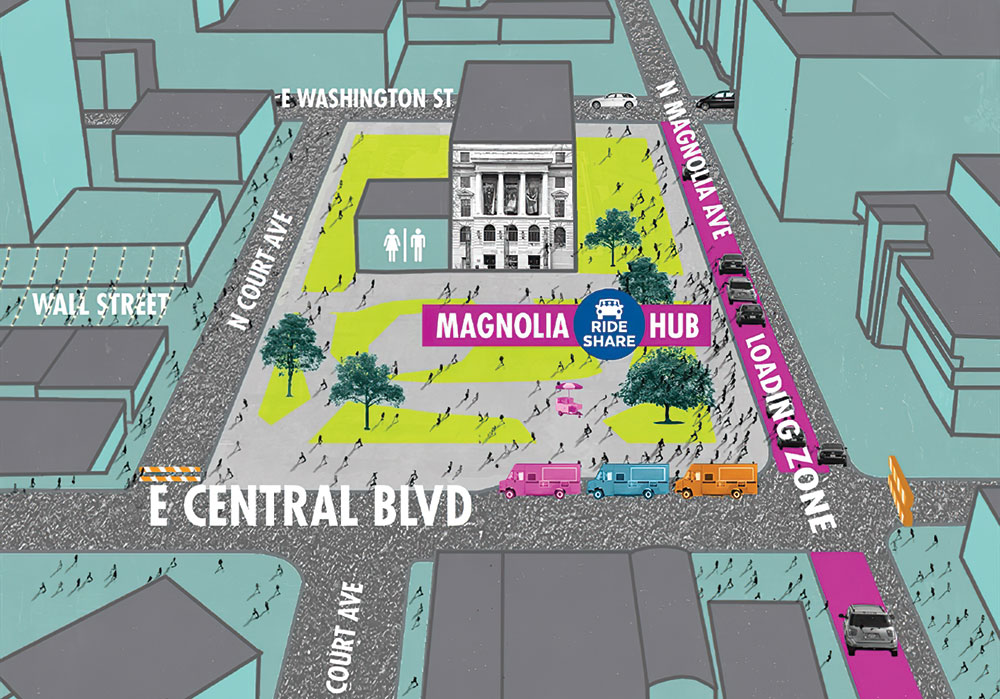

Last year assistant planning division manager Jason Burton, AICP, and Dominique Greco, the nighttime economy manager, worked on a pilot program for weekend ride-hailing hubs for Uber and Lyft and a designated food truck area in the popular Wall Street Plaza in Orlando. Map courtesy City of Orlando.

One of the weekend block parties at Wall Street Plaza in Orlando. Photo courtesy Wall Street Plaza.

Challenges and partnerships with planners

Ultimately, the night mayor's job is a tough one. It's not for anyone with a thin skin. They get an earful from businesses because permitting processes take too long, or code inspections can be too nitpicky, or sundry other things. They get an earful from residents because outdoor music continues past a curfew or it's too hard to find a parking space at night, and on and on. And then, when nighttime managers help devise a solution, the wheels of city government can get bogged down or move too slowly toward a resolution, trying everyone's patience.

Sarah Hannah-Spurlock, Fort Lauderdale's nighttime economy manager, describes it this way: "It can be like wading through mud."

As it happens, one of the challenges that nighttime managers sometimes run into is with their city's planning department. A few nighttime ambassador-advocates observe that city planning doesn't always keep up with the evolution of urban nightlife.

Requirements for soundproofing are often missing in planning policies for mixed-use entertainment-residential areas. Transit routes are often designed or altered based on daytime traffic needs, without much consideration about the nighttime. In Pittsburgh, the zoning code defines a microbrewery as a manufacturing use, not a bar or restaurant. In Austin, Texas, zoning treats bars differently in different locations, with a conditional use permit needed for those outside downtown but not inside the central business district.

"There's sometimes a gap or something lacking in the planning tools," says Brian Block, AICP, who is Austin's nightlife advocate with the title of entertainment services manager within the city's economic development department. Austin has started revising its Land Development Code, and Block says, "I'd like to see more focus and involvement in city planning specifically around nightlife."

In some cities, though, the nighttime ambassador-advocate already works in concert with planners. In Orlando, Florida, assistant planning division manager Jason Burton, AICP, and Dominique Greco, the nighttime economy manager for the Downtown Development Board, handle issues together every week. Last year they collaborated on a pilot program to establish weekend ride-hailing hubs for Uber and Lyft and a designated food truck area at the edges of a downtown bar district after midnight. This required a city-approved zoning adjustment to allow the food trucks.

"We work hand in hand," Burton says about Greco. "It's more of a partnership."

That can be a lesson for cities considering adding their own night mayor. As it is, these types of jobs are only expanding across the country. When the Responsible Hospitality Institute holds its annual summit on city nighttime economy planning, representatives from nearly 100 cities participate, illustrating the potential for more nighttime managers across the country. Cities such as Boston, Minneapolis, New Orleans, and Vancouver have had discussions or requests about adding their own.

"It's real incredible how this phenomenon has grown," says New York City's Rigie, who spoke at last year's RHI summit. "There's a lot of potential for this to take off."

Jeffrey Spivak, a market research director in suburban Kansas City, Missouri, is an award-winning writer specializing in real estate planning, development, and demographic trends.