Planning November 2020

Five Ways to Plan for More Accessible Housing

At least 25 percent of U.S. residents will experience a disability that impacts their daily life. How can we better prepare America's housing stock?

By Steve Wright

More than three million people currently use a wheelchair full time in the U.S., according to the last census. And America is aging at a larger scale than ever before: fewer than eight percent of Americans were 65 or older in 1950, but by 2030, AARP predicts that population will increase to 20 percent. Due to age or other factors, the Centers for Disease Control estimates that one in four people experience a disability that impacts their daily routine during their lifetime.

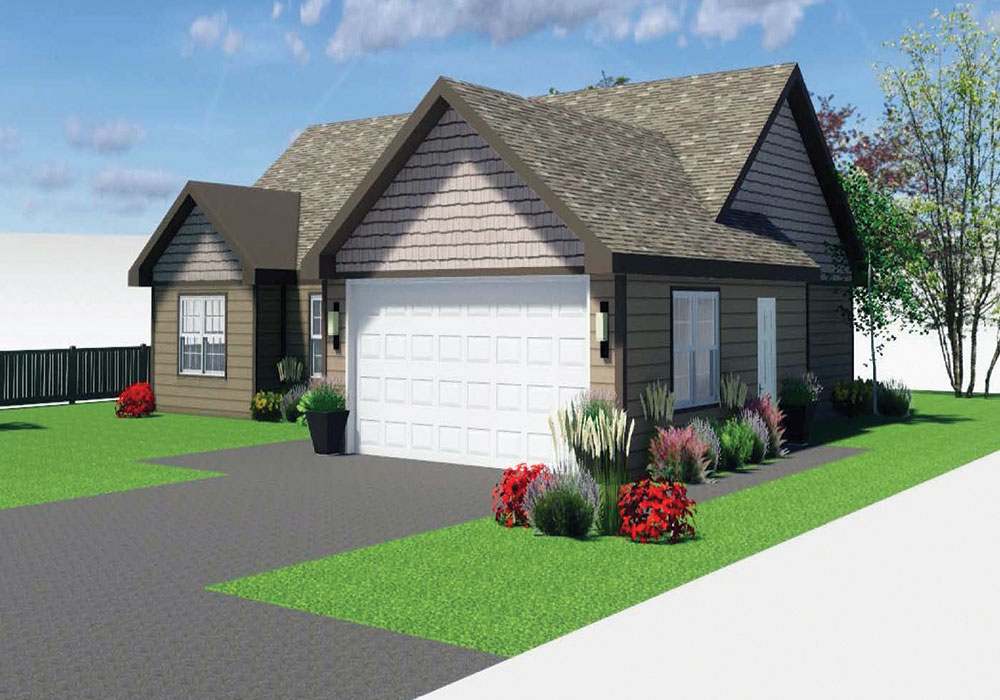

The entrance to this house is equipped with stairs and a wheelchair ramp, both of which complement the overall exterior aesthetic. Photo by Douglas Levere, courtesy IDeA Center.

The increased need for accessible housing

Altogether, these facts point to a desperate and increased need for accessible housing. But according to surveys from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, less than one percent of all housing is move-in ready for wheelchair users, and virtually all of that tiny one percent is newly built multifamily housing.

The desire to age in place should drive zoning and building codes that create homes that are more accessible and adaptable for all. But currently, few planning department policies and practices support move-in-ready accessible housing. Here are some best practices and tools to help you get started on making a change in your community.

1. Change policies to enhance minimum federal requirements

Photo by Clarke Realty Capital, courtesy IDeA Center.

The federal Fair Housing Act requires that all residential (ownership and rental) buildings with four or more attached units have minimum access. In buildings with stairs, all ground floor units must be accessible, and in elevator buildings, all units must have minimum access. In the case of these requirements, "minimum access" means:

- An accessible building entrance on an accessible route

- Accessible and usable public and common use areas

- Usable (wide enough and with lever handles) doors

- An accessible route into and through (no steps or split levels) the covered unit

- Light switches, electrical outlets, thermostats, and other environmental controls in locations that can be reached by a wheelchair user

- Reinforced walls for grab bars

- Usable bathrooms and kitchens, with no island blocking a wheelchair user. The kitchen pictured above in a home for a wounded veteran, for example, accommodates a wide range of users through the addition of adjustable sinks and cabinets, loop-handled cabinet hardware, and appliances that a person in a wheelchair can reach.

Even though single-family housing accounts for more than 70 percent of dwellings in the U.S., there are no federal standards for minimum accessibility — even in stand-alone rental houses. The combination of no requirements for single-family housing and federal fair housing rules not demanding essential roll-in showers means requirements are not matching demand, says Edward Steinfeld, AIA, director of the IDeA Center and the School of Architecture and Planning University at Buffalo, SUNY.

Providing density bonuses and fast-tracking permitting can be incentives to build more accessible units than those required by federal laws, he says.

"Policies that provide incentives to build accessory dwellings or convert single-family homes to two or more apartments can help homeowners extract value from their homes and enable them to remain living independently," he says. "Even fire codes play a role ... overly restrictive interpretation of fire prevention codes can make it impossible for people to add chair lifts to stairways serving second-floor apartments."

To create age- and disability-friendly communities, planners need to ensure that master plans and zoning allow for construction of more affordable accessible housing — and develop better and more accessible transportation options, too.

2. Use land banks to create accessible housing

Photo courtesy DON Enterprises.

Land banks acquire, maintain, and return vacant and blighted property to productive use. Operating as nonprofits, they leverage public and private resources to transform problem properties into community-oriented uses. In this role, land banks serve as the intermediary between local governments, which assist in land acquisition, and community organizations, which need land to advance their missions. The mission often is rehabbing houses or apartments for use as affordable housing. In western Pennsylvania, a disability advocacy nonprofit is using land banks to create more affordable and accessible housing.

Disability Options Network (DON) works with the Lawrence County Land Bank to turn abandoned homes and vacant lots into scattered site housing with roll-in showers, accessible kitchens, and barrierfree entrances. DON has gutted and rebuilt existing abandoned houses (rendering above) and constructed new accessible homes on vacant lots in and around New Castle, Pennsylvania.

"DON's mantra is 'Living at home in the community of your choice is a big part of the American Dream.' The area has a lot of housing in bad condition. As a nonprofit, we can get them for about 100 bucks from the land bank," says Court Hower, DON's executive vice president of community resources and development. "We are creating inclusion. We are rehabbing them and making them fully accessible."

3. List accessible rental and ownership units in public databases

Photo by Kentweakley/iStock/Getty Images Plus.

"In the Puget Sound area, we have a large number of multifamily units being built with accessibility features that exceed the minimum standard of the Fair Housing Act," says Karen L. Braitmayer, FAIA, head of Studio Pacifica in Seattle. Five percent of multifamily units in Washington State must have fully accessible bathing features, turning space in the bathroom, knee space at the bathroom and kitchen sink, work space with knee space and lowered counters, and all operable controls on appliances within the reach range.

But accessible units aren't reserved for people with disabilities (PWD), so inventory doesn't meet demand. Local governments need to create databases where accessible units can be listed when they become available, she says.

"It would be ideal if units were listed when available for rent or sale, and if units could be held for a period of time to allow PWD preference," says Braitmayer, who uses a wheelchair for mobility. Tax or floor area ratio (FAR, which is typically calculated by dividing the gross floor area of a building by the total buildable area of the piece of land upon which it is built) incentives to build accessible single-family housing could be provided, with an emphasis on properties that have low slope routes to public transit or walkability to retail centers.

4. Mandate visitability

Photo by Roman Makedonsky/iStock/Getty Images Plus.

Eleanor Smith, the founder of nonprofit Concrete Change, created the concept of visitability: homes that are not fully accessible, but have one level entrance, a wide threshold, and an accessible bathroom on the ground floor. The photo above shows these external design features, which make it possible for someone who uses a wheelchair to visit neighboring houses that would otherwise be inaccessible to them.

"I oppose [visitability] incentives — [they] must be mandated for new construction of every house in a city or county," says Smith, who uses a wheelchair for mobility.

Builder groups often oppose visitability mandates, claiming they'll halt construction of new homes. But Smith says the notion is patently false. She points to Pima County, Arizona; the village of Bolingbrook, Illinois; and other municipalities where accessible and visitable homes have held and increased in value, and new home starts have not been stifled by existing visitability ordinances and requirements there.

While it is unclear exactly how many homes have been constructed with visitability standards across the country, Smith says more than 60,000 were built under the regulations she championed in these areas and others in the last 30 years.

5. Support everyone by embracing Universal Design

Photo by Clarke Realty Capital, courtesy IDeA Center.

"There is at least a 60 percent probability that a newly built single-family home today will have at least one person with a disability living in it in the next 50 years," says Brian Peters, community access and policy specialist for IndependenceFirst, a disability advocacy and resource center in Milwaukee.

Many planners and elected officials think accessible housing is only needed by people with existing disabilities, Peters says, but according to a 2018 AARP survey, while 76 percent of Americans over the age of 50 want to age in place in their current residence, a third of those surveyed say it won't be possible without major, often expensive modifications, like in the bathroom above.

By promoting accessibility, communities not only support populations who wish to age in place; they also create more flexible, sustainable housing for all. This feeds into the late architect Ron Mace's concept of universal design, which is defined as design usable by all people to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialization.

"We know that an overwhelming majority of older adults desire to remain in their current homes," Peters says. "It makes sense to plan on someone having a mobility disability, whether due to accident, illness, or age."

Steve Wright is a disability rights activist and marketer of design services. For 35 years, he's been writing about design, accessibility, and equity.