June 9, 2023

Non-native English speakers and people with limited English language skills have historically been marginalized and left out of planning processes in both intentional and unintentional ways.

In mostly immigrant neighborhoods in the U.S., where one or more languages other than English predominate, ongoing disinvestment and alienation can directly threaten a community's fabric. Displacement due to new development is a particular risk. This potential place-based harm can compound other traumas and challenges many immigrant communities face.

Disinvestment threatens immigrant communities' cohesion

"For most of my young life, I felt unseen and unheard, and [there was] a sense that I couldn't change anything in my community because of my status as a DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] recipient," says Dayana Molina, a specialist at the Trust for Public Land focused on engaging non-native English and monolingual communities around new parks projects in Los Angeles. "That's the lens that I bring to my work: knowing that sense of not belonging that many communities experience."

Deeply entrenched barriers must be acknowledged and overcome to work toward more meaningful community engagement. Designer Willett Moss, founding partner of CMG Landscape Architecture, has noticed a growing industry parlance around the idea of working at "the speed of trust." The intention is a positive sign, he says, but there's often a discrepancy between aspiration and the actual resources — including time — allocated for it.

"Expectations need to be tempered with an understanding of the amount of investment that needs to be made at the inception of a project to get this right," says Lisa Abboud, president of the multicultural marketing and public engagement studio InterEthnica (a frequent collaborator with CMG Landscape Architecture).

To work toward getting it right and making your community engagement efforts more sensitive to language diversity, consider these approaches.

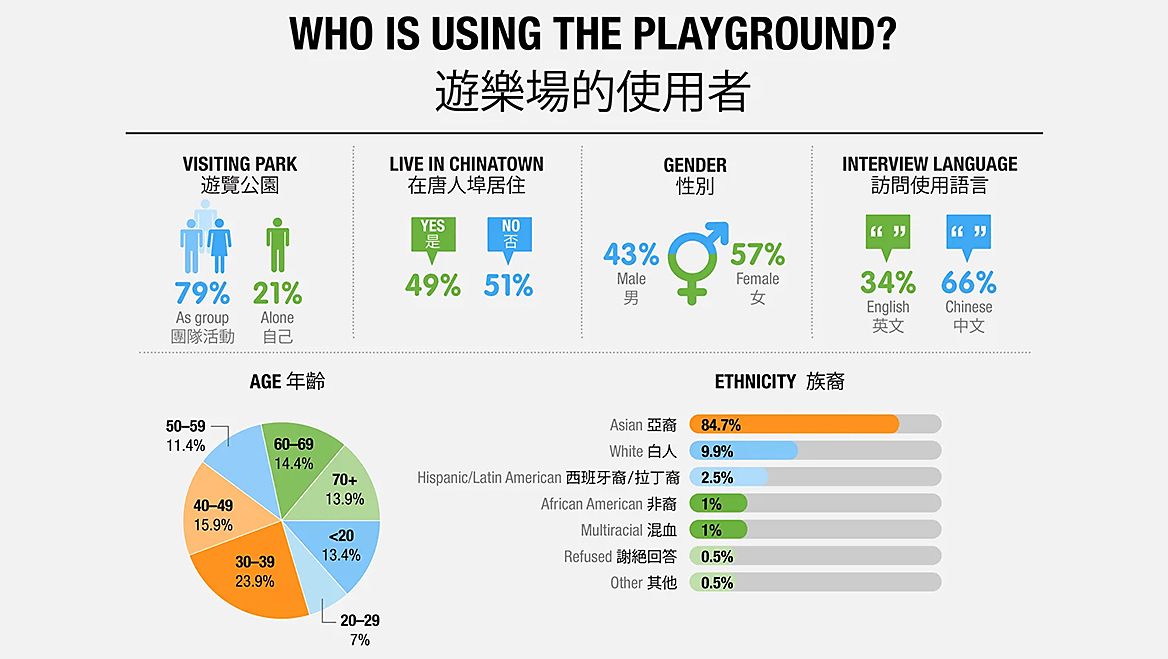

Pairing good visuals with bilingual text in infographics can help participants understand important information, like survey data. Graphic courtesy of InterEthnica.

1. Treat research as a forethought, not an afterthought

Community engagement in general — let alone with groups that require specialized efforts — is often treated like an add-on toward the end of the planning process. But as Mona Abboud, InterEthnica's in-house cultural anthropologist, argues, it needs to be thoughtfully considered, researched, and planned for at the very beginning of the project.

Mona Abboud describes a process that involves demographic research and mapping out all the different cultures and communities that will be impacted throughout the scope of a project. To avoid cliches and tokenism, planners should research the history and culture of people and place, using ethnographic research processes to gather qualitative and quantitative insights. For InterEthnica, that involves developing bespoke public participation strategies for each project — and getting community feedback on those plans.

Allocating resources to spend time getting to know the community and local groups before any engagement directly related to the project even begins is a must, agrees Molina.

"That engagement process in the beginning is so important — going to them and explaining or describing the project and recognizing community leaders," she says. "That's what leads to building trust. Making sure that the first time somebody comes to a [public] meeting isn't the first time they hear about the project."

2. Translate English with care

When working with monolingual communities, planners might think all they need is a literal translation of project and outreach materials. But the way meetings, materials, and social media are translated and communicated, in both directions, matters. Attention must be paid to which words and phrasing are most understandable and relatable.

For a new public realm plan for San Francisco's Civic Center, a multilingual team made it possible to translate materials and conduct focus groups in five languages. Photo courtesy of City and County of San Francisco.

While advising on the development of Taylor Yard, a new 100-acre, rails-to-park transformation in Los Angeles along the wider LA River redevelopment, UCLA's Luskin Center for Innovation Adjunct Assistant Professor Jon Christensen realized something was off. The city's department of toxic substances was holding public meetings after finding significant levels of lead and hydrocarbon-derivative contamination during the project's site characterization phase. But this information, and how it fit into the wider plans for the new park, was being presented in technocratic language that hadn't been adequately translated into other languages — even though nearly half the residents in surrounding neighborhoods primarily speak Spanish.

He enlisted Molina to lead community engagement efforts. She organized a series of focus groups and conversations with community partners to develop a vocabulary that could be used in meetings, presentations, and on social media.

"You don't just get there by translating your English environmental science technical jargon into other languages," Christensen says. "You get there by asking how people themselves talk about these problems and challenges, listening, and being in conversation."

3. Create safe spaces where communities feel empowered to engage

When it comes to meaningfully engaging communities of non-native-English speakers, creating spaces that feel safe and open is paramount. Doing so requires attention and sensitivity to all of the social, cultural, and environmental cues that can make historically marginalized communities feel welcome or unwelcome, as well as paying careful attention to who is — and isn't — present.

"When going about doing any kind of planning work, you should stop before you start and figure out who needs to be in the room," says Mona Abboud.

This becomes even more important when the makeup of the design, planning, and delivery teams aren't reflective of the communities in which they're working.

Planners need to go out of their way to make people feel comfortable. For the Willie "Woo Woo" Wong Playground, facilitators presented in both Cantonese and Mandarin, allowing seniors, young people, and the general public to weigh in on their favorite options. Photo courtesy of InterEthnica.

"Picture a low-income Latina mother living in the Tenderloin [district of San Francisco] coming to a meeting at the Civic Center, and she walks in. How comfortable she will be participating in giving feedback depends on who is there," says InterEthnica's Lisa Abboud. Addressing this could involve asking some members of the design team to not be physically present when sensitive topics are addressed, documenting the feedback, and then presenting it to the full team later.

To avoid what they describe as the "cringeworthy" potential of project teams mismatched with the communities they're serving, planners should be "paying close attention to cues and going out of your way to make people feel comfortable, especially when going into their spaces," says Molina.

In preparing for engagement sessions for the Willie "Woo Woo" Wong Playground in San Francisco's Chinatown, InterEthnica made sure planners in attendance from CMG were well versed in rituals and customs from the community's cultures. In meeting with elders after their weekly citizenship and English classes at a local community center, for example, the delivery team would present them with gifts, followed by a bow.

Importantly, this work should continue throughout the project, says Lisa Abboud. "Before finalizing, go back and say, this is what you said, this is what we heard, this is what it looks like in our rendering — and did we get it right? What would make you feel welcome and comfortable in this space?" Ultimately, Lisa Abboud points out, this work is about empowering the community to become decision makers in the spaces that they are going to inhabit.