Oct. 16, 2025

It doesn't take seeing the brightly painted buses motoring down the streets of Crested Butte, Colorado, to know you're in a unique place. The 1-square-mile community proclaims that it has more cows than people. During the warm months, you may find polka dancers in a park. In winter, neighbors help one another dig out after snowstorms.

"People come here for a reason, and they definitely stay for a reason," says Mel Yemma, AICP, community development director of Crested Butte. "It's not easy to live here, with harsh winters. Housing has gotten a lot harder over the years. It really takes a certain intention, grit, and passion to be here."

Like many mountain towns, Crested Butte was in transition from a coal mining community to a ski resort town, bringing a younger demographic with it. In the months leading into the COVID pandemic, however, there was palpable tension in the air. The median income for a family of two was $70,800, but the median sales price for homes had reached $2.6 million. Just 64 percent of homes had full-time residents, and an overabundance of short-term rentals (STRs) caused officials to cap licenses in 2017 and stop issuing them altogether in 2021.

Troy Russ, the community development director in 2021, recalls there being nearly 900 job openings but just one long-term rental available.

While it was clear that solutions were needed, planners and elected officials wrestled with competing community interests. In June 2021, after officials declared a housing emergency, Russ and others saw an opportunity to create a values-based comprehensive plan — the Community Compass — that they hope will lead to better decision-making now and well into the future.

Ben Wright, handyman and resident of Crested Butte, held a sign at a popular four-way stop for more than a month in 2021 to raise awareness about the town's housing crisis. Source: Crested Butte Community Compass, 2022.

A first time for everything

In 2017, when Crested Butte first capped STR licenses to 30 percent of the homes in town, it was a Band-Aid on a larger problem. Soon after, a house there sold for $2 million. Then, COVID hit in the winter of 2019, and tourists began flooding into the community that summer.

"We definitely saw an amplified angst in the community and big public meetings," says Town Manager Dara MacDonald. "It was sort of a perfect storm for us to garner a lot of community engagement, because there were a lot of visceral feelings out there."

The response from staff was to draft a comprehensive plan, which Colorado state law requires for towns of more than 2,000 people. Since Crested Butte is at just under 1,700 people, that meant the community would have leeway to craft something more geared toward its population.

"We knew we needed to stop being as reactionary as we had been, with no clear forward vision," MacDonald says.

Identifying values

In November 2021, Ian Billick became mayor. The ability to help shape the comprehensive plan was one of several reasons he decided to run. "I saw it as an amazing opportunity to actually have long-term impact," Billick says.

Early on, MacDonald says, Billick and the town council told staff to focus less on traditional comprehensive plan sections and more on what the community valued — and, more importantly, what they would be willing to give up for that value to be upheld. "To have that latitude to focus on the funky people, the painted buses, and the cool things that we all love, rather than more traditional 'check-the-boxes' stuff, was amazing and freeing," she says.

Over a 12-month period, staff heard from more than 1,000 community members. But when they presented the first draft of the plan, Billick and the council members sent it right back. "We needed to make it simpler," Yemma remembers. "So much of planning is storytelling to help the community understand and grasp what its challenges are and how they want to go forward."

By its final version, passed by the town council in November 2022, the plan had identified four core values: authentic, connected, accountable, and bold.

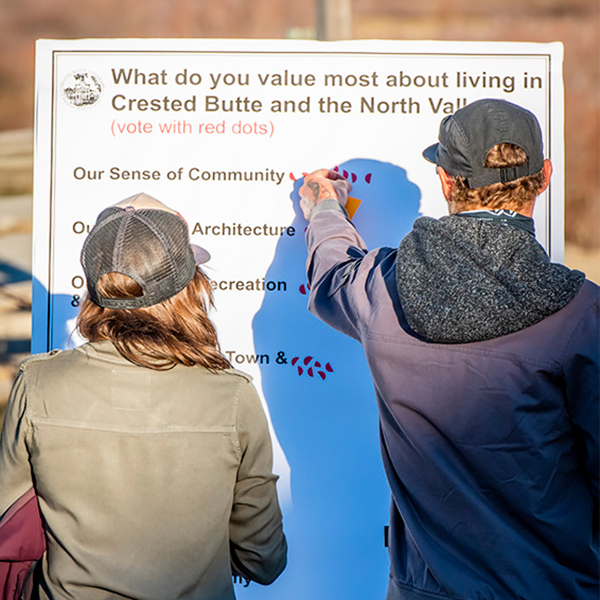

To understand Crested Butte's core values, the town's engagement efforts reached 700 community members and collected 503 survey responses. Source: Crested Butte Community Compass, 2022.

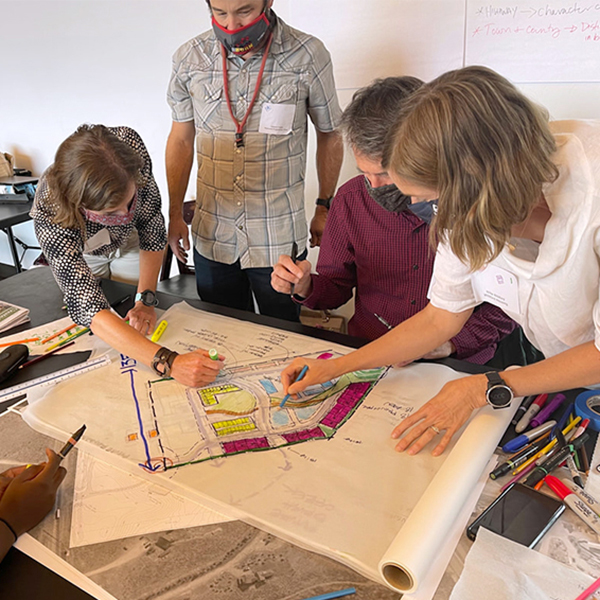

Whetstone Village, an anticipated affordable housing project, hosted a design charette to gather input from community members and housing development experts. Photo by Eric Phillips.

"Traditional comprehensive plans have this physical vision — we're going to have a beautiful waterfront or a vibrant, healthy neighborhood — abstract words for physical things," Russ says."Compass doesn't say anything like that. 'Bold.' 'Connected.' Those values have nothing to do with the physical, but they have everything to do with decision-making."

The plan also listed seven strategic actions, such as having active collaboration and public engagement, accommodating growth in a way that keeps the town's rural feel, de-emphasizing cars, and a five-step playbook for making value-minded decisions.

Tracking change in Crested Butte

Since its adoption, officials have used the framework to pass several projects and initiatives, including a new STR license policy, an all-electric building code for new construction, a transportation mobility plan, and a historic preservation plan.

Crested Butte also agreed to a multimillion-dollar extension of water and sewer services to the Whetstone Village affordable housing project, a 15-acre piece of land south of the town that will add 252 housing units to Gunnison Valley County by 2027. As part of the agreement, developers were required to make 80 percent of the units deed-restricted, with no less than 40 percent of the units serving households below 120 percent of the average monthly income of the area.

Russ, who stepped down from his position in January 2025, says the success of Compass shows planners should embrace community engagement and rethink how comprehensive plans are created, so they can be decision-making frameworks that reflect the values of the community. "What I'm trying to do is set a process up that is resilient and flexible enough to deal with the realities of day-to-day governance and the nuances that you need to make sure planning is relevant," he says. "I think the Compass process reinvigorates and empowers planning."

Mayor Billick believes Compass also shows that while change is inevitable, it's not a bad thing. "People fall in love with a place because of who they are when they arrive," Billick says. "I came here when I was 21, but I will not be 21 and it will not be 1988 in Crested Butte again. But there are elements that you want to see carry forward that are core, right?

"I think the story is how, at least for this slice in time, the community identified what about our past that we wanted to hold onto — but not holding onto it so tightly that we couldn't create the next magic place."