Jan. 15, 2026

A new set of green paths traverses the tree-lined streets of Oak Park, Illinois. Installed in August 2025, they join bike boulevards and greenways that first popped up in the near-Chicago suburb in 2005.

As 15-minute cities and 20-minute suburbs grow in popularity, the adoption of bike and active transportation plans is becoming more common across the country.

But those plans are now uncertain.

This past September, the Trump administration began to pull funding from projects it deems "hostile" to cars, and communities are navigating how to move forward without the funding they anticipated.

Slowing down and speeding up

The Oak Park Bike Plan, which works in tandem with the city's commitment to Vision Zero, received $1.2 million through the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Safe Streets and Roads for All grant program in 2024.

A quick build, like this painted bike lane with a buffer in Cleveland, can create affordable and safer cycling options. Photo courtesy of City of Cleveland.

The program for Vision Zero implementation was paused, however, so the $200,000 match from Oak Park is unavailable, says Christopher Welch, Oak Park's assistant engineer.

"This year, we didn't move forward with any [Vision Zero] improvements, because we're still kind of hopeful that something will change, and we'll be able to move forward with the grant," Welch says.

In the meantime, Oak Park will increase local traffic management and Vision Zero funding by about $600,000, Welch says.

Oak Park is hardly alone. Cleveland adopted its own active transportation plan, Cleveland Moves, in early 2025 after committing to Vision Zero in 2022. The program was awarded federal grants, but assembling local, state, and federal funding has been like "putting together the pieces of a puzzle," says Sarah Davis, Vision Zero coordinator for Cleveland.

The plan has an ambitious goal of building 50 miles of "high-comfort bikeways" across the city in the next three years. In addition, quick-build bikeways — low-cost, temporary, or pilot installations — allow Cleveland to build "cheaper in an era where federal funding is very complicated," Davis says. "We're able to do a lot more with less money."

These builds also help the city identify what does and doesn't work before building permanently.

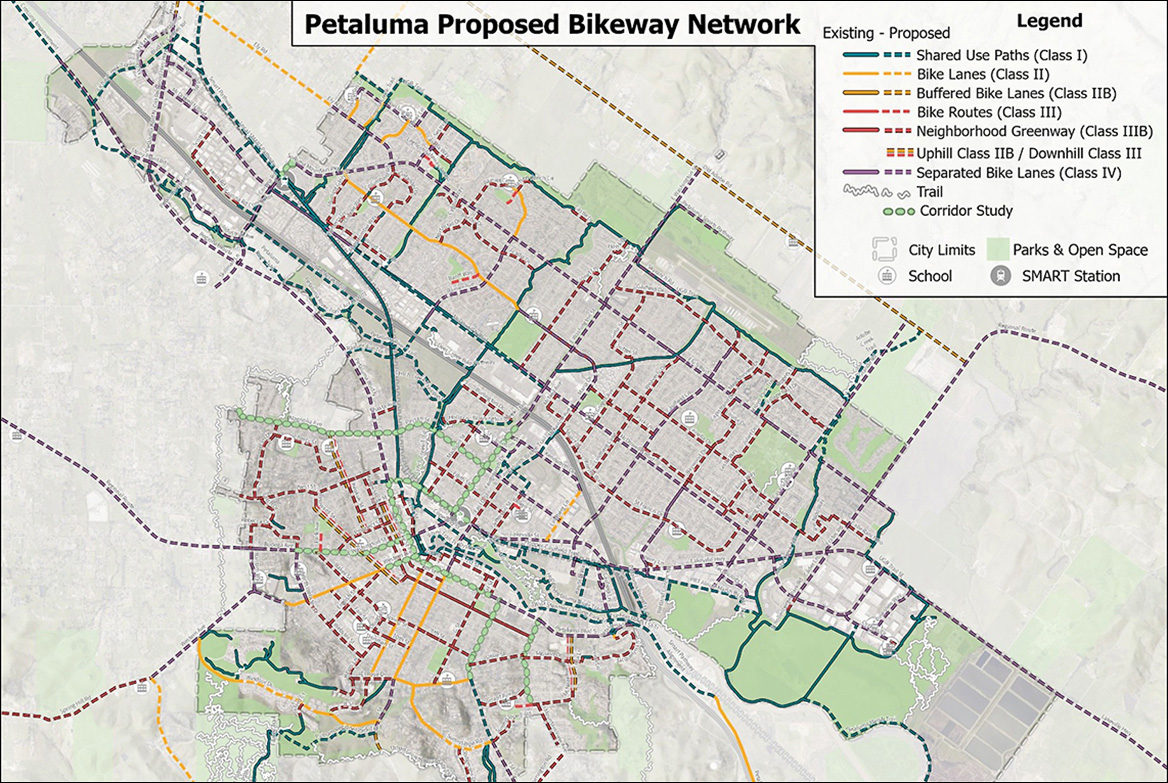

This map of Petaluma, California, proposes various bikeway improvements, from shared use paths to separated bike lanes. Image courtesy of City of Petaluma.

Engaging at the street level

In diverse communities like Oak Park and Cleveland, as well as Petaluma, California, conscientious public engagement can help guide prioritization.

Attending existing community events is essential, "so you're not having people make special efforts to seek you out," says Jared Hall, transit manager of Petaluma, which just released its own active transportation plan.

"We have to make it connect with someone that doesn't live and breathe this stuff," adds Brian Oh, Petaluma's community development director.

For Oak Park, using an online module to collect community feedback was the best route. "It ended up being a really efficient way to collect that kind of geospatial data," says Mark Bennett, AICP, a senior planner with TYLin, an engineering consultant that developed the city's plan.

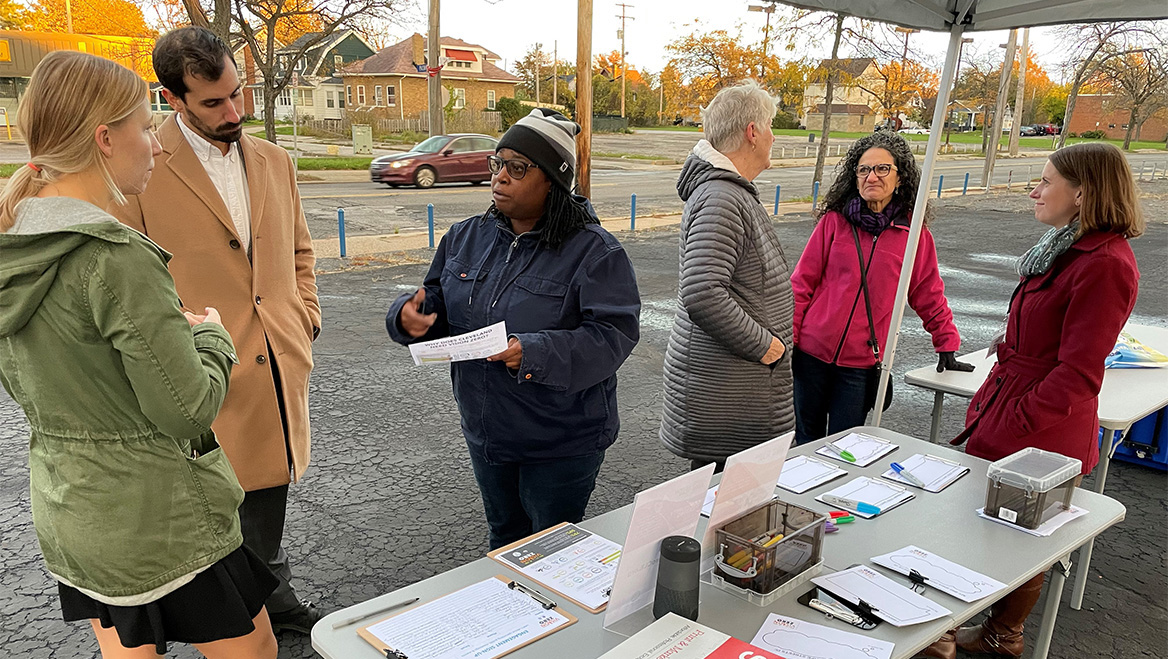

While online engagement in Cleveland was useful, "racially, it didn't align with what our population looks like at all," Vision Zero coordinator Sarah Davis says. Cleveland's population is almost 50 percent Black, and according to Davis, 85 percent of online respondents were white.

Vision Zero Cleveland gathered input from the community at local markets through prompt cards like: "My primary safety concern is?" Source: Vision Zero Action Plan, 2022.

To get more equitable feedback, planners hosted focus groups with underrepresented communities. But Davis says the most applicable feedback came from meeting people in their neighborhoods. "We wanted to be at the farmer's market," she says. "We wanted to be at the corner store. We wanted to catch them where they already were."

Navigating new paths in Oak Park

Back in Oak Park, the 2025 Bike Plan focuses on active transportation to complete daily tasks like going to work or school, says Jenna Holzberg, chair of the city's transportation commission.

Six types of bike lanes will be built, some of which already exist: shared neighborhood greenways, striped, buffered, protected, raised, and off-street. The locations were determined by community comments, an understanding of pain points for cyclists, and traffic and speed analysis.

Oak Park began implementing the earliest phase of the plan update in summer 2025, and it came in almost $600,000 under budget. Bennett says the city will continue painting the pavement with neighborhood greenways and bike boulevards in the short term and move onto more structurally complex additions as research progresses and — ideally — bike ridership grows.