Accessory Commercial Units

Zoning Practice — December 2025

By Bobby Boone, AICP, and Max Pastore

As communities across the country seek more equitable, adaptable, and walkable neighborhoods, accessory commercial units (ACUs) have emerged as a promising, yet underutilized, tool for neighborhood vitality. ACUs refer to small-scale, often homeowner- or tenant-operated businesses integrated into primarily residential lots. These uses, like corner coffee kiosks, backyard salons, or garage bicycle repairs, can strengthen local economies, reduce barriers to entrepreneurship, and develop amenity-rich neighborhoods.

Despite their potential, ACUs remain a fringe zoning concept. Nationwide, few examples exist of communities fully integrating ACUs into zoning, permitting, and development review processes. While Pomona, California, has adopted zoning that allows ACUs by-right, which may serve as a model for other communities, it has yet to see homeowners apply for permits.

This issue of Zoning Practice explores the barriers to and opportunities for ACU adoption. It offers advice for communities considering ACUs through practical recommendations for enabling ACUs as the missing middle between home-based businesses and traditional commercial districts, bridging neighborhood-scaled commerce and community-serving design.

A coffee kiosk operating out of a converted residential garage in Portland, Oregon (Credit: Ren Marshall/Google Maps)

The Relationship Between ACUs and Market Conditions

Aging strip centers, with their larger lot sizes and consolidated ownership, have become ideal candidates for residential redevelopment, often without any retail component. Multifamily residences are driving project outcomes as the highest and best use, often leaving commercial space as an amenity with lower profits. Nationwide, this trend is reshaping the role of retail in communities. And it is perhaps most profound in California, where statewide legislative efforts have aimed to accelerate housing development.

This is the context for Pomona's interest in ACUs. As traditional retail corridors face transformation or decline, Pomona passed ACU legislation to ensure that local entrepreneurs, especially those rooted in nearby brick-and-mortar spaces, have new, flexible options for sustaining their businesses (§550).

Historical Context & Legacy

The idea of small-scale, residential adjacent commerce is not new. Before Euclidian zoning codes rigidly separated land uses, many communities benefited from scattered businesses in residential communities. Streetcar suburbs routinely featured corner grocery stores, sandwich shops, and professional services. These businesses provided daily necessities close to home, often occupying front rooms or converted garages. In this legacy, accessory commercial units represent not a radical departure, but a return to time-tested urban patterns.

The idea of reestablishing small-scale neighborhood commerce in residential neighborhoods is not new. Advocates such as Strong Towns and the Congress for New Urbanism (CNU) have promoted ACUs as a tool for walkable, small-scale commercial reintegration. The revival of live/work units during the rise of New Urbanism in the 1990s also emphasized mixed-use flexibility at the neighborhood scale. Yet, while these units were often envisioned as the modern version of the shopkeeper's flat, they were typically limited to new developments tied to complex form-based codes, placing them out of reach for modest incremental use in neighborhoods with legacy forms of zoning.

Shophouses along Koon Seng Road in Singapore (Credit: Bobby Boone)

Around the world, shophouses are a common feature of urban and suburban neighborhoods, where the ground floor, often fronting pedestrian walkways or public streets, is occupied by commercial uses, while the rear portion and upper floors serve as residential space. These mixed-use buildings remain central to the commercial, cultural, and social fabric of many communities, offering a walkable, human-scaled development pattern that many cities in the U.S. now seek to replicate through zoning reform and incremental infill.

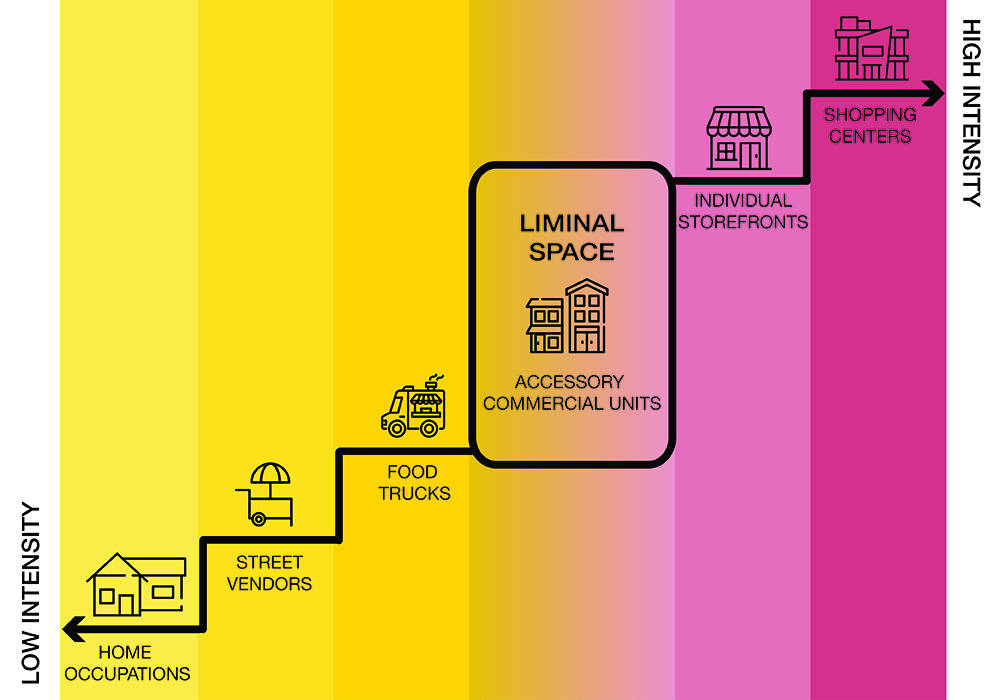

Similarly, the evolution of home occupations, food trucks, and street vending has prompted cities to rethink the boundaries of where commerce belongs. These models have shown that flexibility, cultural responsiveness, and low barriers to entry are vital for local entrepreneurs. However, the regulatory tools that govern them often fall into two extremes:

- Objective standards (e.g., square footage, signage, hours), which provide predictability but can stifle innovation and adaptation

- Subjective criteria (e.g., "neighborhood compatibility"), which offer discretion but risk inequitable enforcement or inconsistent outcomes

ACUs exist in regulatory liminal space, as they are more visible and public-facing than home occupations, but less intensive than traditional retail (Figure 1). They don't sit comfortably in either camp, and zoning codes have largely failed to acknowledge their potential. This gap represents both a challenge and an opportunity. By recognizing ACUs as a legitimate land use type, with tailored standards that reflect their scale, social value, and context, cities can unlock a new layer of neighborhood commerce. They can also reconcile past and present, updating regulatory frameworks while honoring legacy patterns of community-serving entrepreneurship.

Identifying Viable ACU Markets

While ACUs offer exciting potential to localize entrepreneurship, they face real market headwinds in today's retail landscape. Ecommerce has dramatically reshaped consumer behavior, offering same- and next-day delivery for many goods that were once purchased at corner stores or small neighborhood retailers. Shoppers today gravitate toward multi-tenant shopping centers and commercial districts, where proximity to other businesses creates more opportunities for comparison, convenience, and cross-shopping.

A common critique of ACUs is their limited sales potential. For example, can a garage bodega compete with Amazon or a strip center grocer? Especially amid rising construction and operating costs, ACUs must be highly strategic to succeed.

Yet, their strength lies in offering what delivery services cannot: immediacy, intimacy, and in-person experience. The garage-turned-salon with loyal clients, the takeout window that serves fries best eaten hot, or the corner convenience store that sells formula for a fussy infant — these are ACUs that fill real, immediate needs. As more people work from home and spend their time within a smaller geographic orbit, ACUs can meet shifting demand shaped by post-pandemic routines. Success depends on aligning use types with hyperlocal demand, emphasizing quality and proximity over volume and scale.

Market viability for ACUs is also tightly linked to the dynamics of commercial displacement and gentrification. In many communities, small businesses are losing access to affordable retail space due to redevelopment, rising rents, or the proliferation of national brands. As traditional storefronts become unaffordable or scarce, ACUs can offer an alternative typology — one that allows entrepreneurs to operate within or adjacent to their homes, reducing overhead while staying embedded in their communities. ACUs are particularly attractive to entrepreneurs who need nontraditional space formats, who are testing business ideas before scaling, or who seek to serve a hyperlocal customer base with cultural or convenience-based offerings. These uses often flourish when aligned with community identity and everyday patterns.

Precedents

The term ACU is not unfamiliar within planning circles, but awareness among the general public and even permitting staff is low. The term tries to evoke the familiarity of ADU (i.e., accessory dwelling unit), but ACUs typically lack the legislative support, streamlined applications, pre-approved designs, specialized business products, and cultural normalization that ADUs more readily enjoy in states like California. For better or worse, planners and aspiring entrepreneurs are navigating largely uncharted terrain.

One notable exception is Raleigh, North Carolina. In 2022, the city amended its Unified Development Ordinance (UDO) to allow ACUs (defined here as "live-work uses") by-right in residential districts without special or conditional use permits (Ordinance No. 2022–383 TC 469 TC-12-21).

The update included clear limitations, such as excluding drive-throughs, minimizing food and beverage sales, capping floor area at 1,000 square feet or 40 percent of the principal structure, and restricting business hours. This makes Raleigh one of few jurisdictions to formalize ACUs as a permitted by-right use rather than a discretionary exception. The limited number of ACU ordinances nationwide highlights how sparse policy precedents remain and how much Pomona and other municipalities must blaze their own paths (Table 1).

| Jurisdiction | Summary |

|---|---|

| Los Angeles County, CA | Defines "accessory commercial unit" (§22.14010-A) and permits them in the South Bay Planning Area, subject to use-specific standards that specify allowable uses and establish development and performance standards (§23.318.060.2.a) |

| Luddington, MI | Defines and regulates "accessory commercial unit" as an accessory structure for a home occupation (§900.3:6) |

| Muskegon, MI | Defines "accessory commercial unit" (§200) and establishes an Accessory Commercial Unit overlay district (§2328) |

| Stevens Point, WI | Defines "accessory commercial units" and permits them as conditional uses, subject to dimensional standards, owner occupancy, and utility connection standards (§23.01.15) |

| Yorkville, IL | Defines "accessory commercial unit" (§10-2-1) and establishes use-specific standards that prohibit outdoor activities, limit hours of operation, and require ADA-compliant pedestrian circulation and owner occupancy of the principal residential structure (§10-4-16.B) |

ACUs in Pomona, California

Pomona is a medium-sized city (2020 population 151,713) in eastern Los Angeles County, California. In many ways, ACUs are a natural fit for the city. Its large immigrant population, particularly from Mexico and Central America, brings with it cultural attitudes toward space and entrepreneurship that align well with the flexibility ACUs can provide.

At Pomona's planning counter, staff have fielded frequent inquiries from residents interested in getting more out of their front yards. Within Pomona's immigrant communities, there is often a strong sense that deep ornamental yards are a missed opportunity. Why can't that land be used more productively or socially?

In multigenerational households, which are common in Pomona, the demand for flexible indoor-outdoor space is even greater. These households tend to have a more entrepreneurial spirit, with many residents seeking to start personal service businesses such as hair salons, tutoring, tailoring, and small food ventures that respond directly to neighborhood needs and tastes. In this context, the notion of the large, turf-covered front yard as sacrosanct is less true. Instead, there is cultural readiness to embrace incremental, adaptable uses of space, making Pomona especially appropriate for ACUs.

Just as early 20th-century neighborhoods adapted unevenly when commercial uses emerged along new streetcar lines, Pomona's modern effort to reintroduce neighborhood-scale commerce through ACUs will likely look similar. The promise of incremental urbanism is flexibility, and translating that promise into a contemporary regulatory environment also requires flexibility. What seems like a high risk has the potential to deliver high rewards, and Pomona decided the risk is worth it.

A residential neighborhood in Pomona, California (Credit: Wirestock/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

Regulatory Complexity

While the ACU concept is intuitive, crafting a clear zoning definition proved challenging. ACUs occupy an uncertain place between home-based businesses, ADUs, and traditional storefronts. This makes it unclear whether they should follow residential or commercial standards. The ambiguity can confuse city staff and applicants alike. For example, should an ACU have the same signage allowances of a typical storefront or the restrictions of a residential home? Similar questions arise around parking, floor area, and outdoor storage.

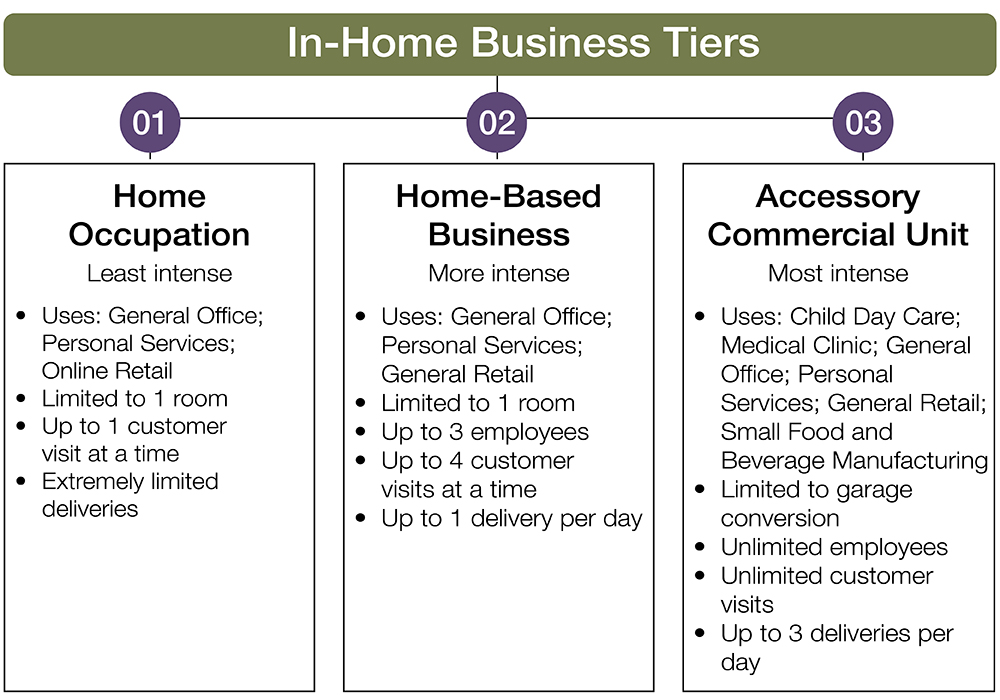

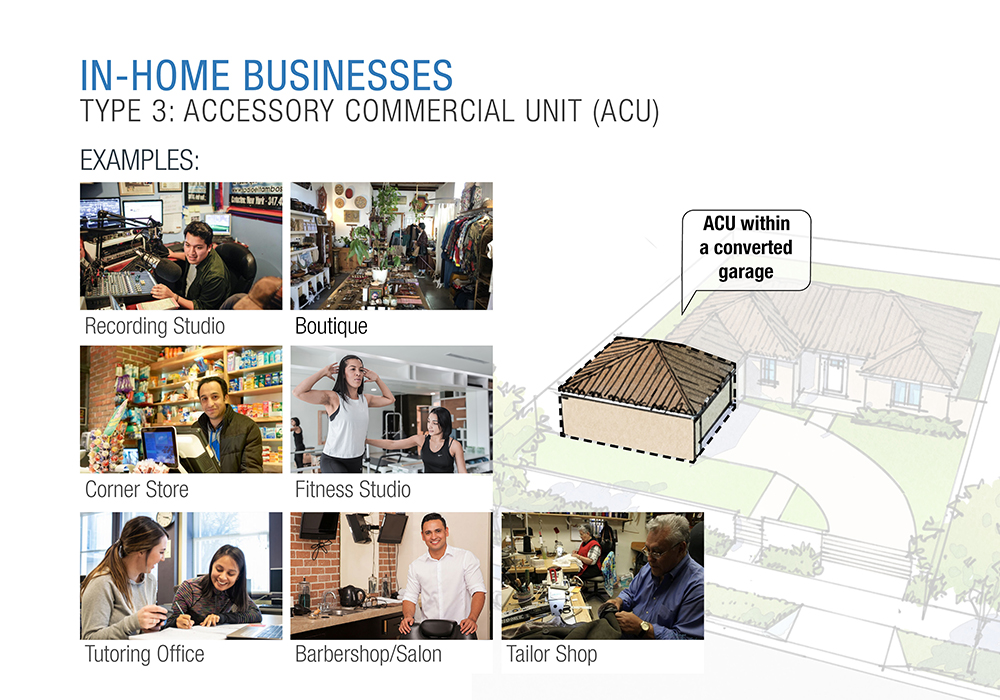

Pomona considers ACUs to be in the same family as a home occupation or home-based business. And its official definition makes this relationship clear: "The secondary use of a single-unit home's garage for the purpose of conducting a business enterprise that is operated by the homeowner, with a greater degree of activity than a home-based business" (§550B.12).

The city permits all three options by-right but treats them as a spectrum of intensity (Figure 2). While this by-right approach aims to be straightforward, questions still come up at the planning counter that require staff to interpret the nuisances.

The complexity does not end with zoning. While Pomona controls its zoning, the city does not control other regulations that impact ACUs. For example, health and fire regulations fall under the jurisdiction of Los Angeles County. This division of authority creates added layers of difficulty. Not only do city and county staff need to coordinate code updates to ensure that rules complement one another, but applicants must also navigate a permitting process that requires approvals from multiple agencies. These layers of confusion and inconsistency increase the risk of delay, higher costs, or contradictory guidance, and they can discourage the very entrepreneurs that ACUs are intended to support.

Barriers to Entry

ACUs require meaningful physical transformation, such as converting garages or portions of homes into permanent commercial space. This contrasts sharply with more flexible entrepreneurial formats like home occupations, food trucks, or street vending, which require lower financial and procedural investment.

In a context like Pomona, where food trucks and street vending are widely accepted and require neither construction permits nor major upfront costs, the added burden of securing permits and paying for permanent building conversions can make ACUs less appealing or competitive. Applicants may also face uncertainty about whether their project must comply with more expensive commercial building codes rather than residential codes, depending on the proposed use. These requirements significantly raise the barrier to entry for small entrepreneurs, limiting who can realistically participate.

Customer Base

Even once an ACU is permitted and built, questions of economic sustainability remain. A shop located on a quiet cul-de-sac may struggle to draw sufficient customers, while one located along a walkable block or near a collector street may thrive. The siting and design of ACUs will likely align with block type, street hierarchy, and neighborhood context to maximize their potential.

In Pomona, however, the customer base for ACUs is not an abstract consideration. It is rooted in the lived realities of its communities. Many immigrant households already value space that can flex between residential and productive uses, and there is strong entrepreneurial energy aimed at hyperlocal personal services such as hair salons, tutoring, tailoring, childcare, and food preparation. These businesses often thrive not by pulling in customers from across the city, but by serving immediate neighbors and extended networks within walking distance. This means that, while placement along higher-traffic blocks will matter, the strength of cultural and community ties may allow some ACUs to succeed even on the quietest residential streets. Pomona decided not to restrict ACU placements based on street types. Any home garage located in a residential-only lot is eligible to be converted into an ACU, so time will tell.

Ultimately, customer acquisition and retention for ACUs depends on more than location. It also requires recognizing and supporting the community-based economic practices already present in Pomona. These practices view front yards, garages, and shared household space not as ornamental, but as vital assets in sustaining family livelihoods and neighborhood life. In this way, what appear as implementation challenges also present planners with opportunities to better align zoning reforms with the cultural realities and entrepreneurial spirit of the communities they serve.

Community-Centered Planning: A Collaborative Approach

The successful integration of ACUs into a city's regulatory and cultural fabric requires more than zoning reform alone. Because ACUs sit at the intersection of residential life and neighborhood commerce, their rollout depends on trust, clarity, and a planning process that feels collaborative rather than top-down. Planners play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between policy ambition and community acceptance. Ensuring trust and clarity might involve the following steps.

Step 1: Test Standards with the Community

Beyond one-on-one support, ACUs benefit from transparent rules generated from community collaboration. ACU regulations drafted in isolation — and not asked for by the public — can miss opportunities to align with neighborhood priorities or respond to lived realities. Regulations developed to explicitly solve a community's problem, such as a lack of neighborhood retail within walking distance, are more likely to gain traction and trust.

Walking stakeholders through hypothetical ACU scenarios to surface concerns and opportunities can be particularly effective. For example, how might an ACU hair salon function differently on a cul-de-sac versus a collector street? What design features, hours of operation, or parking arrangements would make residents feel more comfortable with a food-preparation business operating out of a garage? Such exercises transform abstract policy into tangible questions that residents and policymakers can engage with directly. Consider engaging stakeholders early in any code drafting, but only after planning staff have hypothetical scenarios that stakeholders can easily react to.

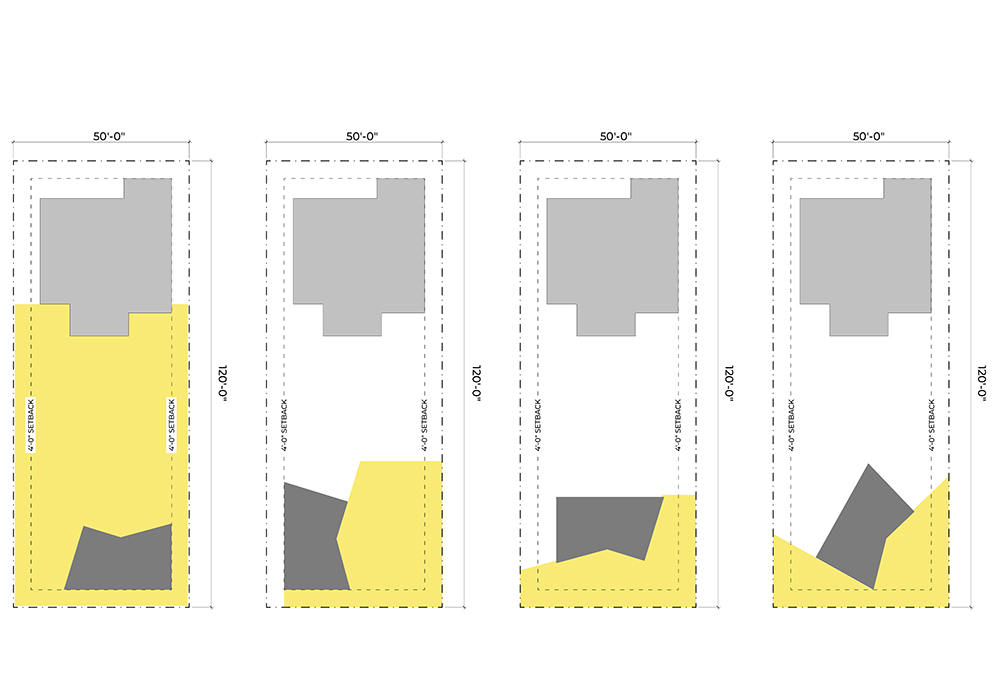

Pomona embedded these kinds of scenarios within its larger public outreach process when the city rewrote its zoning code. While ACUs were ultimately limited to existing garages as a first phase of implementation, planners framed the conversation more broadly as a rethinking of what should be allowed in front yards — including what kinds of fences and walls should be allowed. This made the most sense for Pomona because ACUs could be framed as a potential solution to a problem frequently asked at the planning counter: Why can't I do more with my front yard? At pop-up outreach events, staff illustrated what a typical front yard in Pomona could look like under different zoning regulations, with ACUs presented as just one possible option (Figure 3). As part of this outreach, examples of activities that might take place inside ACUs were also shown, allowing residents to weigh in on which uses they found more or less desirable. This approach grounded the policy discussion in visuals and choices that felt familiar and relevant to the public.

Public engagement strategies look different depending on the community. Regardless, successful processes often combine broad-based outreach — such as surveys, open houses, and translated materials — with targeted focus groups in neighborhoods most interested in ACUs. This allows planners to balance neighborhood concerns (noise, traffic, parking) with the flexibility small businesses need to thrive. In Pomona, engagement with immigrant and multigenerational households was essential, since these communities already saw the home as a flexible economic and social asset. By elevating these voices, planners ensured that ACU regulations not only reflected technical feasibility but also resonated with community values.

Step 2: Form an Interagency Working Group

Even the most thoughtfully written ACU ordinance can stall if there's confusion between zoning, health, fire, or building departments. Because ACUs sit at the intersection of multiple regulatory domains, clear cross-agency alignment is essential. Cities that have streamlined ADU or food truck permitting often use interagency working groups to hash out code conflicts, identify overlapping standards, and build staff capacity. These models can inform a governance framework for ACUs.

Key strategies include

- establishing shared review protocols that define which departments review what (e.g., zoning for location, fire for egress, health for food handling) and in what order;

- developing a unified ACU checklist or portal, akin to one-stop-shop permitting for other uses; and

- training frontline staff across agencies to understand ACUs and communicate consistent expectations to applicants.

Step 3: Minimize Discretionary Reviews

Pomona showcases how ACUs occupy a unique space in the regulatory landscape, neither fully residential nor traditionally commercial. To unlock their potential, cities must move beyond permissive (by-right) code language and toward an intentional framework for integration and promotion. This framework aligns by-right zoning, permitting, and public safety standards with entrepreneurial fever and unmet community needs.

Similar to food trucks and street vending, traditional zoning and permitting processes are often mismatched to the scale and intent of ACUs. Applying these same review standards used for commercial storefronts can result in excessive delays, over-engineering, or outright rejection. However, development review, when adapted, can be a powerful tool for ensuring ACUs are adopted as a viable offering.

Planners and local officials can streamline ACU approvals by incorporating ACUs into minor use permit or administrative review categories, allowing for fast-track decisions when use types meet predefined criteria. For example, allowing low-intensity ACUs like therapy studios or craft production to proceed with minimal review, while requiring a discretionary use permit only for uses with parking or health impacts. Alternatively, they can establish overlay districts or rezone to clearly define where ACUs are allowed and what standards apply, particularly in residential zones with historically commercial characteristics or along alleyways and corner lots.

A corner convenience store in the Bywater neighborhood in New Orleans, a city with a long history of corner shops in predominantly residential areas (Credit: Infrogmation of New Orleans/Wikimedia)

Step 4: Help Applicants Navigate the Process

The role of planners extends beyond drafting code language. They must also guide policymakers in understanding the practical implications of new regulations and help residents and entrepreneurs navigate the permitting landscape. In practice, this often means walking applicants through steps that can otherwise feel daunting, particularly when multiple agencies are involved.

Clear communication materials are a crucial part of this process. Application checklists, illustrated guides, and FAQs written in plain language (and multiple languages where relevant) can reduce uncertainty for residents while saving staff time. In Pomona, staff have learned that many prospective ACU applicants are first-time business owners. Resources that demystify basic requirements, such as when commercial building codes apply or how to coordinate with county health and fire officials, are as valuable as the zoning itself.

Step 5: Establish Pre-Approved Plans

A critical constraint for many would-be ACU operators is costs, particularly for designing, permitting, and constructing spaces that meet building code and zoning standards. Cities can learn from the growing success of preapproved ADUs and modular housing models.

Municipalities can create or license a set of pre-reviewed plans for modular ACU products (e.g., detached kiosks, converted garages, or alley-facing pods) that meet base code requirements. These can

- reduce upfront design costs;

- increase certainty in approval timelines; and

- provide consistent aesthetics that match neighborhood character, avoiding the need to create separate design standards.

Additionally, there is a significant opportunity to develop site plan standards that promote both streamlined approvals and design predictability. These standards can include clear requirements for setbacks, adjacency to existing structures, and compatibility with neighborhood character, offering a regulatory framework that addresses common concerns about variability and visual intrusion in residential areas. By codifying these design parameters, municipalities can ensure consistency without stifling architectural diversity.

Several jurisdictions offer precedents for this approach. For example, Los Angeles's ADU Standard Plan Program enables homeowners to select from dozens of pre-approved, architect-vetted designs — dramatically reducing permitting timelines and design costs. Similarly, some cities have piloted pre-approved plans for modular tiny homes and vendor carts, demonstrating how off-the-shelf design can be deployed at scale to support incremental development.

Alternative configurations for Los Angeles's pre-approved, city-provided YOU-ADU plan (Credit: City of Los Angeles)

Applied to ACUs, this model not only lowers barriers to entry but can also serve a placemaking function. The visual presence of well-integrated, easily recognizable ACU structures — such as similarly designed corner kiosks with walk-up windows — signals active commerce within the residential fabric. These subtle cues spark neighborhood curiosity and visibility, reinforcing a sense of discovery and local identity in the same way wayfinding and storefront variety animate traditional shopping districts.

Conclusions

While explicit zoning authorizations for ACUs remain rare, their re-introduction into residential-only neighborhoods could be transformational for interested cities. Legitimizing small-scale commerce in these neighborhoods, ACUs offer planners a more grassroots tool to strengthen neighborhood economies, foster entrepreneurship, and bring everyday amenities closer to where people live. The implementation challenges go beyond updating the rules, but also minimizing institutional, cultural, and economic hurdles.

Pomona's first pass at allowing ACUs by-right demonstrates the complexities of re-introducing a previously marginalized retail type. While complicated, the city found success in rooting its ACU approach in community conversations about the use of front yards, embedding ACUs within a broader zoning rewrite, and foregrounding the entrepreneurial spirit of immigrant and multigenerational households, Pomona demonstrates how planners can translate a novel idea into by-right zoning that's backed by the community. Raleigh's example, along with Pomona's, points to the beginnings of a policy trend that other cities can adapt to their own context.

For planners, the lesson is clear: Reintroducing ACUs into residential-only neighborhoods offer promise but require market viability, technical creativity, and community-centered collaboration. Successful implementation requires zoning and other codes that are flexible yet coordinated across agencies, processes that support first-time entrepreneurs as much as seasoned business owners, and outreach that treats residents not just as neighbors interested in mitigating adverse impacts, but as future entrepreneurs shaping their local economy.

About the Authors

Bobby Boone, AICP

Max Pastore

Zoning Practice (ISSN 1548-0135) is a monthly publication of the American Planning Association. Joel Albizo, FASAE, CAE, Chief Executive Officer; Petra Hurtado, PhD, Chief Foresight and Knowledge Officer; David Morley, AICP, Editor. Learn more at planning.org/zoningpractice.

©2025 by the American Planning Association, 200 E. Randolph St., Suite 6900, Chicago, IL 60601-6909; planning.org. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without permission in writing from APA.