Dec. 8, 2025

As the tech industry builds more data centers for cloud computing and artificial intelligence (AI), communities across the country face greater demand on their local power grids, creating growing concerns about electricity rates and system reliability. In 2023, data centers gobbled up about 4.4 percent of the country's total electricity and could account for up to 12 percent by 2028, according to a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory report released last December by the U.S. Department of Energy.

The surge in usage has raised questions about who pays for these grid upgrades. In Louisiana, consumers tried to force tech giant Meta to disclose its expected energy usage at a new AI data center that will be powered by the state's largest utility. However, a judge ruled that the company did not have to provide project details to state regulators.

What if, though, a data center operator generated its own power from renewable energy like wind, solar, or other non-carbon sources? Could that lessen the local impact and make data centers — and the economic and sustainability benefits they potentially bring — easier to swallow?

Officials in DeKalb, Illinois, thought so. In late 2024, the city received a proposal from Donato Solar of Deerfield, Illinois, and its affiliate, Gail Technology, to construct a solar farm and two data center buildings on 30 acres adjacent to a subdivision of townhouses and condominiums. Gail Technology said the site would be a self-sufficient operation with limited water use and the ability to channel excess electricity to the local utility company.

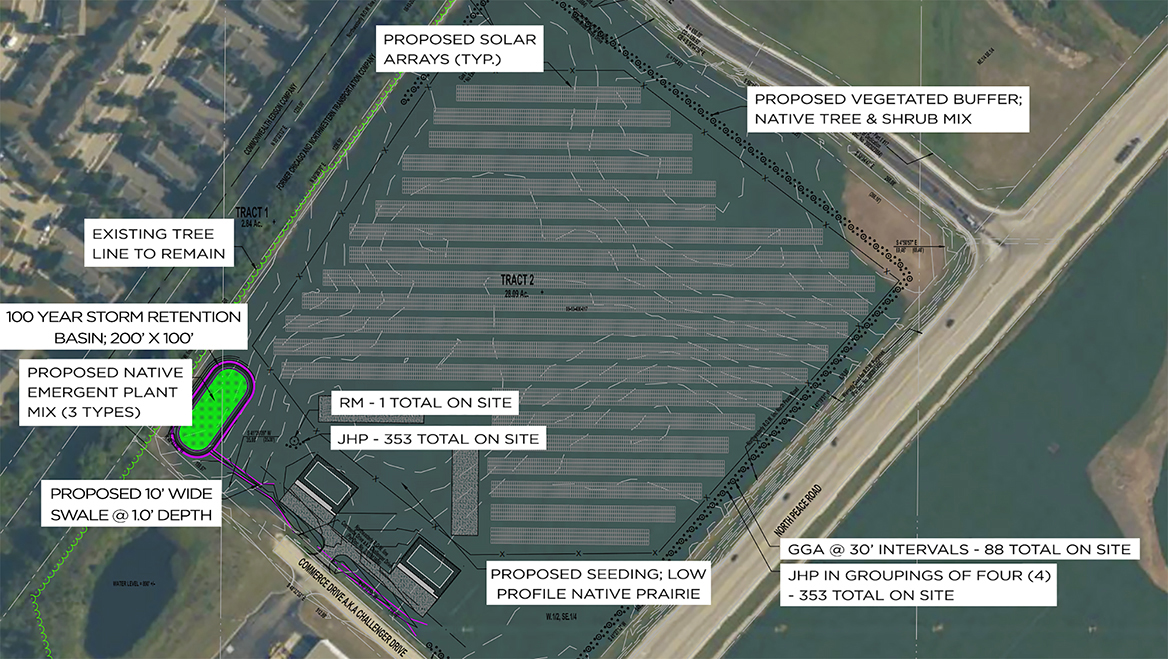

The proposal from Gail Technology and Donato Solar for a ground mounted solar field included native tree and vegetation buffers and tree-lined screens to address potential noise and sight concerns from residents. Image courtesy of City of DeKalb.

The project anticipated creating 60 to 70 construction jobs and up to eight tech positions to manage site operations, and the city projected the business would generate about $85 million in annual tax revenue. Because excess power would go back to the utility grid, city officials also saw the prospect of reduced fossil fuel use and lower energy costs, according to the planning department's analysis.

Earlier this year, Dan Olson, AICP, DeKalb's planning director, indicated that the project had support from the city's planning and zoning commission. The city provided details of the concept plan to residents who lived near the proposed site in January 2025, and some attended a commission meeting later that month to ask questions of a representative from Gail Technology.

The project also had support from Mayor Cohen Barnes, who said the project was preferable to other potential uses, like a trucking operation or industrial facility. After months of discussion, staff recommended approving the Donato solar farm and Gail data center.

That's when things went sideways.

In September 2025, after dozens of residents spoke out against the project at planning and zoning and city council meetings, city officials rejected the proposal. The public outcry led to an obvious question: What went wrong?

A new way to reduce the impact on residents?

For a college town mostly known for producing corn and soybeans, DeKalb and the surrounding county have become something of a renewable energy hub with wind turbines and solar farms, including one that SunVest Solar operates at the municipal airport.

In 2024, the city annexed, rezoned, and approved a concept plan for PureSky Energy to develop a ground-mounted solar farm on 42 acres that aims to support the city's goal to serve residents with locally produced renewable energy. Larger projects that will deliver power to the utility grid are planned outside the city over the next two to four years, including a 170-megawatt project from Red Maple Solar and a 300-megawatt solar farm from Burr Oak Solar.

DeKalb also is home to a 500-acre Meta data center using 100 percent renewable energy. The tech firm opened its first DeKalb data center in 2023 and expanded its footprint from two buildings to five, with an investment of more than $1 billion. In November 2025, DeKalb officials received a proposal for a 560-acre data center to be located just south of the Meta facility.

Olson believes combining zero-carbon solar energy with a data center can "result in a reduction of both operational expenses and the environmental impact of the data center's energy consumption," and the Donato Solar-Gail Technology project was viewed as supporting DeKalb's 2024 sustainability plan. Although short on specifics, the plan urges local leaders to embrace renewable energy, when possible, to reduce its carbon footprint and foster local economic development. This is aimed, in part, at attracting green businesses.

Meta's DeKalb data center is supported by 100 percent renewable energy from two wind energy projects in Morgan and DeWitt counties. Image courtesy of Meta.

Despite pockets of success, there are "surprisingly few" examples of big data center developments that are mostly powered by clean energy, says Wilson Ricks, an energy systems researcher at Princeton University. He suggests that the current national political environment, which is less supportive of renewables, has been a limiting factor.

But that could change. "Data center demand seems to keep growing, natural gas supply chains are strained, and there is a huge existing pipeline for renewable energy and battery development in the U.S.," Ricks says. "Our research has shown that a huge amount of load growth can be supported [with] hardly any increase in fossil generating capacity."

One such initiative is in Storey County, Nevada, where Crusoe Energy and Redwood Materials aim to jointly develop and operate a solar-powered data center that creatively uses repurposed electric vehicle (EV) batteries for grid-scale energy storage. The county's board of commissioners underscored the project's importance when it approved a special use permit in April 2025 for the data center to be paired with a 12-megawatt solar field at the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center, according to Planning Director Kathy Canfield.

At a county commission meeting held earlier this year, Canfield said the project fit well in the industrial center because it "has grown to become a major regional hub for distribution, alternative energy production, digital data management, and highly intensive and experimental industries."

Data demand isn't going away

Back in DeKalb, the planning department faced headwinds as residents organized after the January 2025 commission meeting. After the city scheduled the public hearing in September for the Donato-Gail project and included more details about its size and scope, homeowners turned out in force to voice concerns about noise, energy, water usage, the safety of battery energy storage systems, and the project's proximity to their homes. Residents also were fearful that the industrial facility would decrease their property values and put an unfair financial burden on the community.

Despite developers' assertions that solar fields and data centers can make good neighbors, the commission members unanimously rejected the proposal based on the strong neighborhood opposition, setting the stage for a contentious city council meeting days later when the motion to approve the project failed 5-2.

After the vote, Dekalb's Mayor Barnes was critical of the planning and zoning commission's rejection of the data center plan, saying it was "out of scope" and based on subjective decisions, rather than an objective review against the comprehensive plan.

Meanwhile, as demand continues to grow, Olson says DeKalb has not wavered from its commitment to data centers and solar energy. "This was a site-specific issue that came up," he says.

Olson also takes a pragmatic view of public opposition and advises developers to engage proactively with adjacent property owners before submitting applications. He also says it would be helpful to keep planning and zoning commission officials updated about their roles and responsibilities, including reinforcing after findings of fact reports and supporting documentation before meetings where they expect larger than normal resident turnout.

"With cases like this, you have to refocus and make sure they understand what they are supposed to do," he says.