Nov. 14, 2025

In just a decade, pickleball has become not only the fastest-growing sport in the U.S. but also the source of a fast-spreading land use conflict. Thousands of cities have converted tennis courts or built new ones to meet demand, often in residential areas and with little thought to acoustics or compatibility. The result: noise complaints, lawsuits, and court closures that pit neighbors against players, with all involved looking to city hall for help.

A new kind of neighborhood noise

The noise from pickleball might seem harmless. How loud could a plastic ball being hit by a wooden paddle be? But that friendly "pop" carries. A single strike can be 20 decibels louder than tennis, and it happens up to 900 times per hour per court. Convert one tennis court into four pickleball courts and you get 3,600 sharp, high-frequency impulses every hour.

Compounding the problem, these sounds fall squarely in the range where human hearing is most sensitive. They are brief, irregular, and impossible to tune out. Physiologically, they trigger the body's fight-or-flight response. Over time, fatigue, irritability, and disrupted sleep can lead to health impacts. Factoring in laughter, chatter, and day-long play, one can start to understand why nearby homeowners might take exception.

In response, cities often first turn to local noise ordinances, only to find they were never designed for this kind of sound. A-weighted decibel limits measure steady noises well, but they miss the piercing quality of short, high-frequency pops. But even when readings fall below legal thresholds, residents still suffer.

Zoning Practice offers a framework that balances demand for pickleball courts, neighborhood compatibility concerns, and legal risks.

Meanwhile, code enforcement staff rarely have instruments or training for managing this type of noise, and citations can be awkward when the offender is the city's own recreation department.

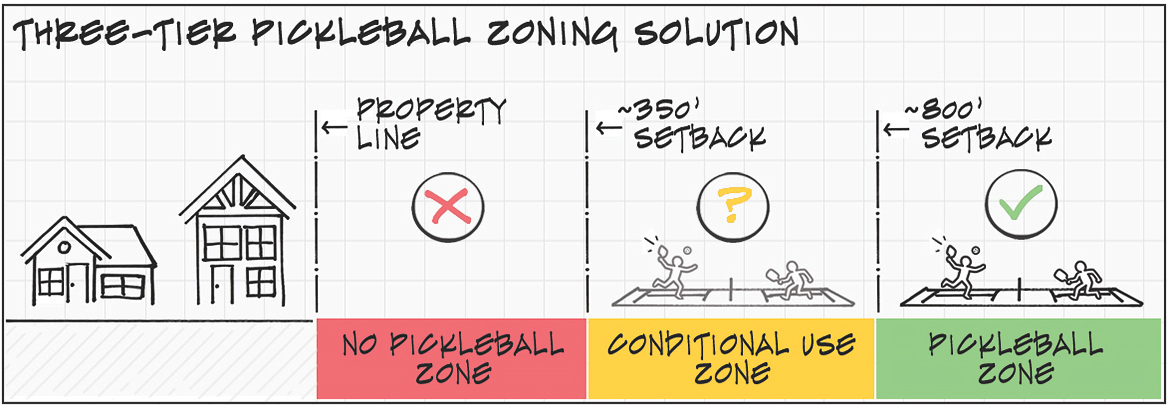

But planners are well-equipped to handle this challenge, with tools — such as setbacks, conditional use permits, and public hearings — to separate incompatible uses before construction begins. Pioneering communities have shown the way with a three-tier permitting framework based on distance from homes and other noise-sensitive sites:

PROHIBITED ZONE: Within the closest setback zone, pickleball is simply not compatible because it cannot be adequately mitigated.

CONDITIONAL USE ZONE: In this middle zone, courts may be approved with a conditional use permit (CUP) if mitigation is demonstrated and neighbors are notified. CUPs are important because they allow planning departments to revisit issues when conditions — or complaints — change.

BY-RIGHT ZONE: Although the popping noise can travel 1,000 feet, depending on weather and reflections, serious conflict is unlikely beyond about 800 feet. In this far zone, courts can be permitted as of right.

Making mitigation work

Experience from across the country suggests a toolbox of mitigation fixes might work — but each has its own strengths and weaknesses. Using quieter equipment, such as "whisper paddles" and foam balls, substantially reduces the sound volume. But players don't like using these substitutes, and this approach requires on-site management to ensure no one is using loud paddles. Alternatively, requiring courts to be in enclosed buildings would also solve the noise issue, but it might deter those who are looking for outdoor activities.

There are other options, however, that planners can select to mitigate noise.

Go long with your setback distance

This requires no expense, no supervision, and is easy to measure. By increasing the distance between the sound source and the listener, it reduces sound energy and gives the other tools a chance to work.

Sometimes, it is OK to put up barriers

Ten-foot vinyl "AcoustiFence" panels and similar products are a possible solution. But because sound radiates in all directions rather than in a straight line, noise will go over the top — potentially impacting two-story homes or nearby housing units that are higher than the panels. Also, barriers are widely disliked because they add expense, require maintenance, and block visibility for police, players, and neighbors.

Limit hours and days of play

Ambient noise drops in evenings and on weekends, making the pickleball pops extra burdensome. Setting limits — such as no games after 6 p.m. or on Sundays or holidays — can send the signal that the city values neighborhood well-being as much as recreation.

Illustration by Michelle Whitman.

How to make sure setbacks don't set the game back

The most consequential challenge for planners is choosing the minimum setback from residential property lines. Smaller setbacks of less than 250 feet have low success rates even with a combination of aggressive barriers, quiet equipment, and limited hours. Larger minimum setbacks of 250, 350, or 500 feet will still need help from one or more of these mitigation strategies.

Another challenge is ensuring that these same zoning standards apply to city-owned and park-district courts, as well as courts within housing developments, country clubs, and the backyards of private residences.

Zoning codes require frequent updates to keep up with novel land uses. More than 20,000 zoning authorities nationwide now face the same question — how to manage a popular but noisy activity that crosses departmental boundaries.

Planners can lead the response. By integrating acoustics, public health, and fairness into zoning practice, they can prevent conflict, reduce litigation risk, and model transparent governance. Doing so reaffirms the profession's core mission: protecting the health, safety, and welfare of our communities.